Kinga and I went to Auschwitz-Birkenau today.

It’s only now that I can appreciate the scale of the Holocaust. Reading Hitler’s Willing Executioners, seeing Schindler’s List, thumbing through albums – it’s not the same. Walking under the sign, “Arbeit Macht Frei,” standing in a gas chamber, walking along the barbed wire, standing by the railroad tracks where the selection was made – only then did the number of Holocaust victims (up to ten million) begin to take on any personal, tangible significance for me.

Auschwitz (the main camp — Auschwitz I) is surprisingly small. A former Polish army base, it doesn’t have such an immediately ominous feel if you ignore the barbed wire and guard towers. Single and double story buildings laid out in a grid, with grass growing in between and birds singing. It could easily be mistaken for an old prison. In fact, that’s really what Auschwitz was.

Despite it’s being associated with genocide, it wasn’t an extermination camp, per se. It was a prison and work camp. That’s not to say that death wasn’t everywhere. Indeed, it was. But it was not a death factory on an imagination-defying scale.

Birkenau was.

Birkenau is three kilometers from Auschwitz, and is actually one of several sub-camps. It was known as Auschwitz II, and it served one purpose: destroying humans.

Birkenau is Auschwitz, for Auschwitz is the synonym of death in the Holocaust, and Birkenau, with its stark and lethal geometry, is the machinery we always imagine when we think “concentration camp.” If one can use the words “stereotypical concentration camp,” then that’s the perfect description of Birkenau.

At Birkenau, Nazis had two gas chambers and (as I recall) six crematoriums. Nazis processed humans like animals – herded out of the cattle cars, stripped naked, gassed, shaved and checked for gold teeth, then burned.

It’s the monotony of Birkenau that is sickening. A mile and a quarter by a mile and a half, it’s an enormous camp that had three hundred barracks and housed up to 100,000 people. About sixty of the barracks remain intact: forty-some brick and twenty-some wooden structures stand in the camp, with countless chimneys marking the ruins of the rest.

Most all of the barracks are open, and most all look the same. It’s that monotony – after a few barracks, you don’t even go into them anymore – that made me realize the true horrific scale and monstrosity of the Holocaust. Nazis lulled themselves into a rhythm of killing that resulted in literal mountains of corpses.

Something had to be done, so they started burning bodies. But this was not efficient – shooting people, then making huge bonfires. No – much more efficient to make an assembly line of death. And that’s what they did at Sobibor, Treblinka, Birkenau, and many extermination camps. Day in and day out, trains arrived, people were slaughtered, and the Nazis went back to their warm barracks and listened to Bach and wrote letters to their wives. Assembly line – everything at Birkenau screams it. Lines of barracks, dissected by a railroad track, surrounded by a fence. It’s geometrical, exact death.

Death times one point five million, to be precise. That’s the death toll of Auschwitz, and it means as you walk along the grounds, you’re walking on literally blood-soaked earth. It’s one of the few places in the world, I would say, where you can throw a stone and know it will probably land within a foot of where someone died. Within inches. Rather, at the very spot.

You walk in the barracks, running your hand along the bunks, realizing that every single morning, the inmates awoke to find someone else had died in the night. And as you’re running your hand along the bunks, you realize that they died in this bunk. And in this one. And in this one. In all of them, chances are.

There is not an inch of that ground that has not seen death, and it seems to root the buildings to the place and make it difficult to lift your legs as you walk.

Tourists crawl over Auschwitz. They’re literally everywhere. Tour groups weave in and out of the barracks and through the streets, making it impossible to be alone. And the languages you hear – Japanese, Arabic, Spanish, French, English, Hebrew, everything.

And you hear German. We bumped into at least two German tour groups, and it somehow seemed eerily appropriate to hear German in that place.

Birkenau, in contrast, has much fewer tourists. Its sheer size, compared to Auschwitz, means more privacy, less competition with other visitors. The parking outside is probably one-tenth, if even that, of what’s outside Auschwitz, and yet it makes such a bigger impression.

My stomach churned the entire time, and for one brief moment, I was sure I was going to vomit. It was in one of the exhibits in Auschwitz, housed in the barracks. Hair – a literal mountain of hair, shaved from victims’ heads after being gassed. The hair provides proof to anti-Semitic Holocaust deniers because there remain traces of Zyklon-B in the matted, filthy hair. There are over fifteen-hundred pounds of hair in the exhibit, and at the near wall, just as you enter, is the spot I grew so nauseated that I had to go to the window to get air.

Fabric, woven from human hair, intended for clothes. An entire bolt of cloth – who knows how many were produced in total – with bits of hair placed on top.

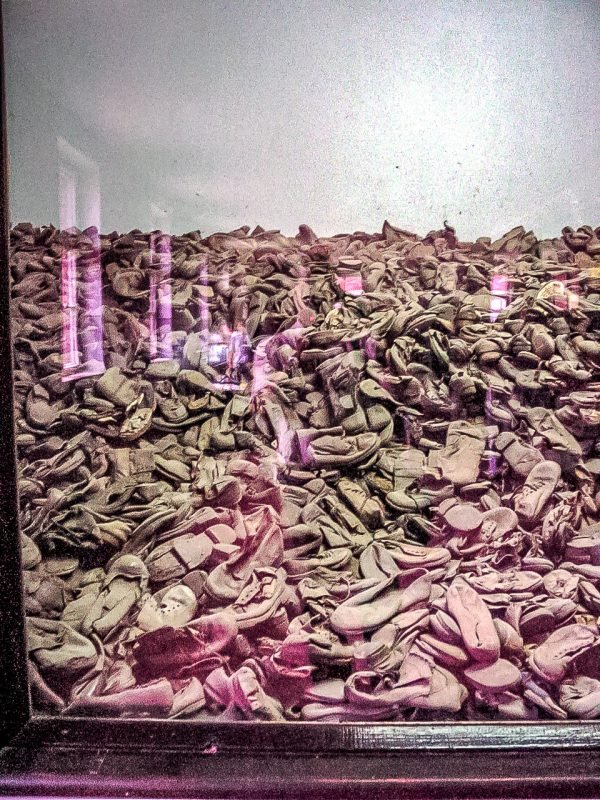

There are hideous mountains throughout the exhibits: of shoes, of combs, of suitcases, of pots and pans and other kitchen utensils, of twisted eye-glasses, of artifical limbs. There are piles of shoe-polish tins, face-cream tins, forks, spoons, baby shoes.

It’s too much. You just want to scream.

The most tragic part for us, in the twenty-first century, I told K as we walked along the train tracks in Birkenau, is that there are thousands, even millions, of people who would gladly see this camp open and operational again. I wasn’t just referring to the anti-Semitism that still haunts our world, the young Neo-Nazis who deny that the camps were death camps – Hitler didn’t know; Hitler got a bum rap; and other absurdities – and yet know what the camps were used for and would like to see them killing again. I was referring to the guards and others responsible who are still living, some of whom no doubt regret that Hitler didn’t finish what he started.

What would have happened if Hitler had won the war? Birkenau leaves little doubt. The Jews would be non-existent, as would Slavs, Roma (Gypsy), blacks, Asians, and anyone else who offended Nazi sensibilities.

What’s most astounding about the concentration camps is that they, to some degree, cost Hitler the war. Hitler could have fought to a stalemate, then resumed again when his forces were strengthened. But what did he do? When supplies were needed at the front, instead of decreasing the shipments of victims to camps and using those trains to get supplies to the army, he increased the number of shipments. The pace stepped up as the inevitable loss approached. The Nazis’ hatred literally consumed them in the end. Its irrationality overwhelmed the cooler heads needed for military strategy, and reduced Nazi leadership to foaming-at-the-mouth, obsessive maniacs.

It’s not just the scale of victims that comes into sharp focus at Birkenau. The number of perpetrators – mostly German, but with help from other collaborators – required to murder that many people becomes obvious. It was not a handful of Nazis that did this. A significant percentage of the European population (again, the vastly overwhelming majority Germans) was mobilized to slaughter ten million people like household pests. And yet, at the Nuremberg trials, Allies brought forward only 24 indictments, resulting in 10 death sentences.

What about the others? If there are surviving victims sixty years later, there are surviving perpetrators. How do they live with that? How can they sleep knowing what they did and what they saw?

It’s another aspect of the Holocaust that defies all sense of reason and decency.

Last night, looking at pictures I took, it seemed like a nightmare. Even when I was living the experience, it seemed dream-like and intangible. Walking around the camp, seeing the barbed wire and barracks and train tracks, imagining what it was like to be interned there, thinking about what happened – it all seemed unreal.

Such is the scale of the Holocaust that even when you’re in the center of the hell it created, it seems impossible. How can people do this to one another? You stand there in the incontrovertible proof of the Holocaust’s reality, and yet it seems insanely unimaginable. “What kind of an individual would think of such a thing, let alone put it into practice?”

I’ve seen it, but I’m even further from understanding it.

(Re-published for the yea write. Photos re-edited June 2021.)