We’ve had a couple of lazy days now, but our last day we were determined to pack as much into it as possible. That’s how it seems looking back over the pictures of the day, but in fact, we really only had one major item — the Warsaw Uprising Museum — and the rest was just improvisation. I’ve learned during our time in Warsaw, though, that if there’s any city open to improvisatorial sightseeing, it’s this one.

Uprising Museum

Was it worth it? A last-ditch effort to overthrow the grip of a brutal dictator from the West encouraged by the vague promises of an equally brutal dictator from the East — in hindsight, wasn’t it destined to fail? Surely the Poles knew that they couldn’t trust anything Stalin said. Certainly the Poles didn’t think the Germans would let such violent insubordination just disappear as a footnote in history. So why do it?

That’s hindsight. In reality, it was probably at the same time simpler and more complicated for that. For the individual “soldiers” fighting for Poland in the Uprising — and I use quotes certainly not in any negative sense — it was a chance to level the game. Death had touch everyone by then, and it probably didn’t take a lot of convincing to get the average male Pole to take up arms. There were many likely thinking, “We’re all going to die from this occupation anyway. We might as well take some Germans down with us.”

But those ultimately calling the shots in London, the government in exile — did they have a hard time making that decision? Did they honestly think that anything could come of it? Were they blinded by patriotic war-time zeal for revenge? Or was it something more? Or less? I really don’t know enough about the Uprising to do more than raise those questions, and the museum does a good job of raising those questions. But I’m not quite sure that was its goal.

There was one portion of the museum that left me a little frustrated. In a passage leading from one portion to the other were exhibits of the modern Polish army, with video footage of men disassembling and assembling various weapons, taking part in exercises, discussing missions in Iraq and Afghanistan. It really felt like an advertisement for the army. I’ve nothing against that, but it seemed a little out-of-place there in a museum about the Uprising. Perhaps it was a not-so-subtle statement that something like that won’t happen again.

One would hope not.

Lunch

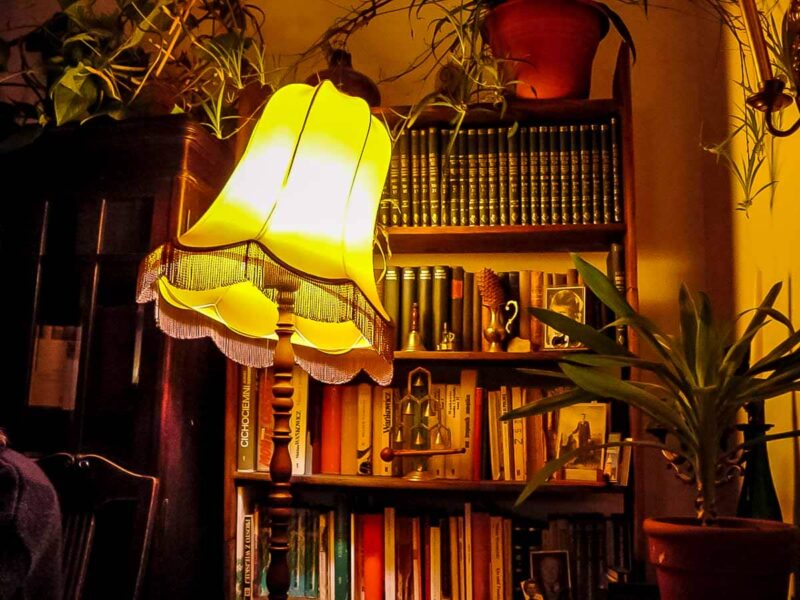

We had to eat at one of those ulta-hip, ultra-modern restaurants while in Warsaw, where you really pay a ridiculous amount of money for a ridiculous amount of food.

“We’re going into a restaurant that’s little more, well, everything than where we normally go,” I explained to the kids.

They got it.

Mostly.

Dom Sierota

K and L recently listened to a Polish kids book about Korczak and his orphanage. It really didn’t go into any details about the tragic yet in some ways beautiful ending of the story; instead, it just went over the revolutionary way Korczak ran his home, with kids making the rules, meting out punishments, cooking and cleaning.

The fact that he marched with his kids to the trains that took them to their deaths in Treblinka was left out, I think. It’s not a topic for a kids book, the author must have thought. Yet there’s a beauty in that: he had several opportunities to escape. People tried to convince him to go into hiding. Yet he refused.

Much to our surprise, the site is still an active orphanage. It turned out to be quite close to the museum, so before lunch, we headed over to find it.

It was haunting to watch my children play on the grounds of that orphanage. Every time E is scared, I ask him, “What’s my job?”

“To protect me,” he replies without hesitation.

Can I always do that? In pre-war Poland, was that possible? What if I was overcome with consumption and K, too? How could we then protect our children? What if we were imprisoned by an occupying power because of our religion or ethnicity and then systematically murdered? How could we then protect our children? It made me wonder if that’s a bit of a lie. A well-meaning lie, a statement that we have every intention of preventing from slipping into falsehood, but ultimately a lie all the same?

Naturally, one can’t function thinking that way, and we all live our lives as if nothing tragic is going to happen to us.

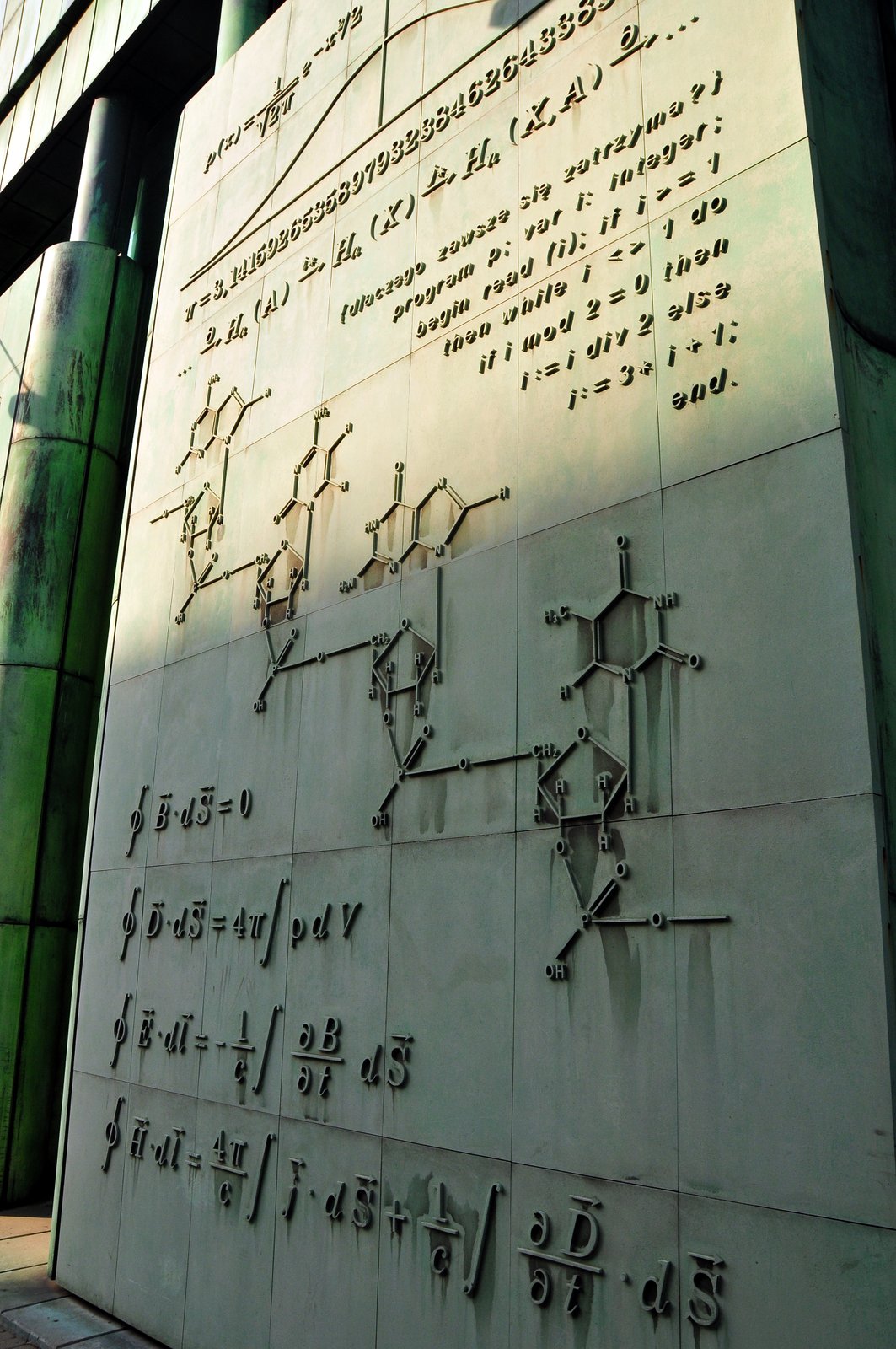

University of Warsaw Library

After lunch, we headed back toward the river so we could try the University of Warsaw Library again.

Two things were different this time: first, the wicker basket swing — for lack of a better term — was unoccupied, so the kids headed straight for it.

(E yesterday said, “That looks like a bee hive.” All the adults looked at it, thought for a moment, and agreed.)

The second: we could go onto the rooftop garden.

“As far as I’m concerned, this is the best thing about ‘New Warsaw,'” K proclaimed. Some interesting ideas, for sure. The vines growing along the sides will eventually cover the whole structure, and I’m assuming this will serve to keep the hot sun out in the summer. Perhaps it will even have an effect in the winter. And it looks modern and fantastic (as in the adjectival form of “fantasy”) and all that, but I was honestly left just a little cold. Maybe that was a microclimate all the green produces…

Holy Cross Church

“Want to go see where Chopin’s heart was buried?” Not the most inviting notion for a five- and ten-year-old, but still, historic all the same.

Visiting churches in Poland used to be such a stressful experience for me. As a non-Catholic, I always felt like I should perhaps be there. I felt like I was intruding somehow. The fact that Polish churches are rarely if ever devoid of penitent worshipers in prayer regardless of whether or not there is a Mass being celebrated didn’t do much to ease the sense that I was barging into some place I had no business being.

Now, I go in and behave like I’d normally behave if I were going to Mass. I make the sign of the cross after dipping my fingers into the holy water fonts at the entrance. I find a quite spot and pray for a few moments. (With the Boy joining me, we whisper an “Our Father” together at some little side altar.) I feel like I belong. Mostly.

Ghetto Wall

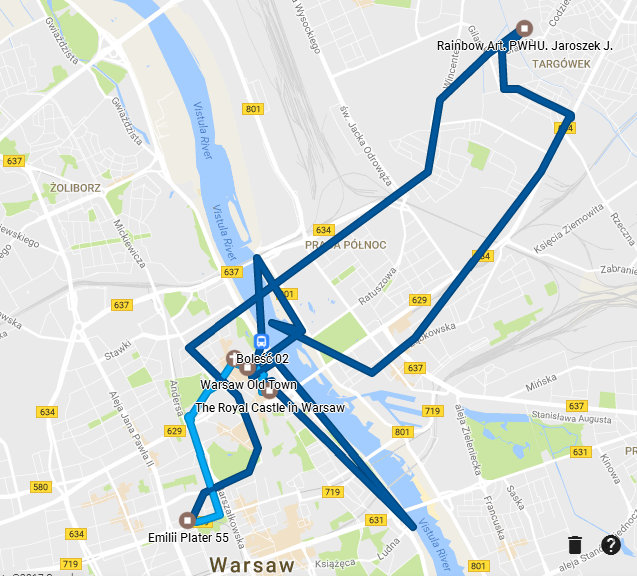

If I hadn’t been really looking for it, if I hadn’t had my phone in my hand with Google Maps showing me theoretically where it was, and if I couldn’t read Polish, I wouldn’t have found it. I wandered around the block, looking here and there, following every little alley to its end.

It all started with a hunt for a beer. Not just any beer: Ciechan Pszeniczne Wędzone. Wheat beer made from wheat that had been smoke cured?! It sounded like heaven. The friend who recommended it told me where I could find it, which was quite near to our apartment, so after dinner, off I went. I found the location, but unfortunately, it wasn’t shop; it was a bar. I wasn’t really willing to go in and have a drink by myself — though in hindsight, why not? who says I had to enjoy it slowly, or even drink it all? — so I accepted my self-imposed fate and started back. Then I remembered: before we left the States, K and I had made a list of all the places we wanted to visit in Warsaw, and one of my additions was the Warsaw ghetto wall, or at least a marker. And I remembered looking at that map just a couple of evenings ago and realizing how close it was to our apartment. And I realized I was standing in that general area. So out came the phone and off I went.

At first, I thought this was it.

It was about the right height. It looked old, tired, worn.

“Surely,” I thought, “there would be some kind of sign, some kind of indication that this is the only remaining portion of the Warsaw ghetto wall.”

I kept looking. Between two blocks of apartments there was a courtyard. All the entries from one street were closed. “Perhaps from the other side.”

And then I finally found it. “Memorial Location” in Polish with an arrow leading down a dark corridor.

At the end, another sign. I went right first and found a wall higher than I ever imagined.

Bricks were missing, which had been taken to Holocaust museums in Melbourne, Houston, and most significantly, the Holocaust museum, Yad Vashem in Israel.

What as most striking was the fact that it still stands between to apartment blocks.

One could look out of one’s kitchen window (literally: one of the apartments was fully lit and I saw that these rooms are the kitchens) and see one of histories most brutal episodes. There were a couple of plaques, but nothing else. It was all so tucked away that you would have to be looking for it to find it.

The second segment of the way was a little more like I would have imagined it, except for the poorly translated yellow sign announcing “Night rest” from 22:00 to 10:00. Apparently, someone — or several someones — had visited the wall and raised a commotion late at night. Hard for me to imagine how that’s possible, but there it was: “Night rest.”

Final Thoughts

I came to Warsaw last week with certain expectations. I’d always been a Krakow fan myself. After all, everything there is old, not just rebuilt to look old. Warsaw was a city of gray, a city that was sad and perhaps tired. Maybe that was the Warsaw I first met in the mid-1990’s, but it’s certainly not the Warsaw of today.

For one thing, there are tourists now. There have been times as we walk down the street that I’ve heard everything but Polish from all the people we pass. The Italian restaurant just outside our apartment complex is always fluttering with Spanish, English, and other languages, and they seem to have a whole community of Indians to deliver food by bike via Uber EATS. When I first arrived in Poland in 1996, the sight of a non-white would send me in to paroxysms of excitement, and it was all I could do to keep from sprinting to them, hugging them, and declaring, “My God! Someone who doesn’t look like me!” (In the States, I think we tend to take diversity for granted.) Now, it’s no big deal.

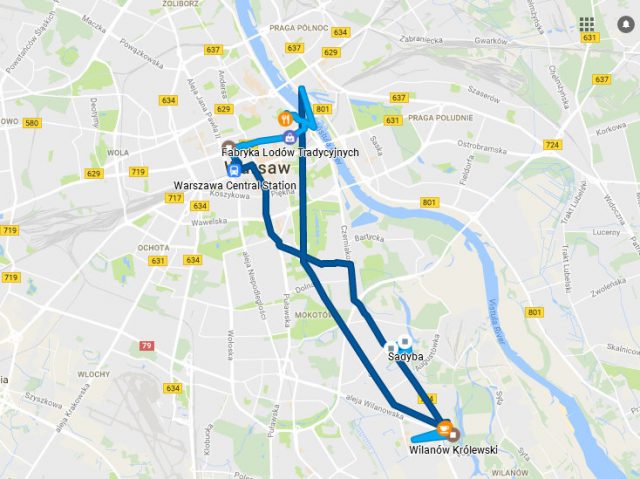

Another difference: the metro. We have used it so much that I can’t imagine what we would have done without it. Well, we would have ridden busses and trams, but they’re such a pain to figure out, route- and scehdule-wise. A subway is simple: get on, wait, get off. When I first visited Warsaw, the subway was a newborn, with barely four or five stops. Now it’s a little toddler, with a full, long main line (a lovely blue line) and a second, growing, red, M2 line. Will it ever catch up to NYC, London, or Berlin? No way. But I don’t think that will keep it from trying.

A third difference: I don’t know that, other than Amsterdam and perhaps Berlin, I’ve seen a more bike-friendly city. Dedicated bike lanes everywhere (well, almost), and bike rental points all over the place.

Bottom line: if someone told me, “You have to move to Warsaw,” if someone held a gun to my head, I would not blink, I would not worry, and I’d grow to love this city as my own.

We will definitely be back.

Step Totals

Step totals (though not necessarily for the whole family) :

- Saturday 20,342

- Sunday 10,524

- Monday 25,304

- Tuesday 18,552

- Wednesday 22,799

We never tried to maximize steps, and we used the public transportation system quite a bit. All told, that’s just about 42 miles of walking according to FitBit.