This woman has watched too much Scooby Doo.

Slippin’ and Slidin’

Got into a discussion on Twitter with a Christian about morality. I made the point that Christianity invents the idea of sin (the transgression of a diety’s law) and then sells the solution (Jesus). My interlocutor quickly moved to the “you have no grounds for morality if you don’t believe in a god” argument. I said,

I know what you’re getting at. I’ve seen it all before. It’s a tiresome road to travel down. Your god commands the stoning of incorrigible children (Deut 21:18-21), so I don’t think believers in the Bible can take the moral high ground as you’re trying to do.

The interlocutor replied,

What you just cited was never Carried out. Even the Talmud says this. This was stated by Moses to put fear into GROWN children to obey the commandments to love their mother and father.

To which I responded,

Carried out or not, it was commanded. By your god, no less. You can’t deny that. The fact that it wasn’t carried out goes against your assertion that morality comes from your god. If it wasn’t carried out, it means people realized it’s a sick command.

To which she replied,

How could my God command it if he doesn’t exist?

I answered,

Just because I say “Juliet made a bad decision” doesn’t mean I have to believe she existed. I’m working within the framework of your holy book. It’s that simple.

What I learned from this exchange is the slithery, slimy nature of religious discussions. One topic slides off to another and to still another. Exhausting.

Before and After

Lightroom’s “Content-Aware Fill” function is improving…

Before

After

Games and Sorting

First Tournament of the Season

Starting R&J

Babcia’s Candle

Any time the sky began growing dark with threatening clouds, Babcia would always shuffle to the kitchen, light a votive candle, and place it in a plate of water.

The motivation behind the small plate of water was obvious: it was protection against an unintentional fire. The bottom of the candle could get quite hot, after all — an entirely reasonable precaution.

The candle itself, though, was to ward off the approaching storm. I’m assuming prayers accompanied the candle, but they must have been silent because the only thing I ever heard Babcia say was, “I must light a candle to keep the storm away.”

If the storm never appeared or the clouds dissipated completely, I’m sure this felt like confirmation of the ritual’s effectiveness. But it didn’t always work. What then?

Looking back on it, this is the same approach Christians take to prayer in general. When a believer prays for something and God appears to have answered the prayer, then it’s confirmation of prayer’s effectiveness. But what happens when God doesn’t seem to have answered the prayer? Most Christians simply move the goalposts.

Let’s say a young child runs out into the road after an errant ball toss and gets struck by a car. The child’s family rushes out to the child lying on the street, praying all the way. If the child gets up, the prayers were answered: God saved the child from all harm. If the child gets taken to the hospital but survived, the prayers were answered: God saved the child from serious harm. If the child ends up paralyzed because of the accident, the prayers were answered: God spared the child’s life. If the child ends up dying, the prayers were answered: God has taken the child into eternal bliss.

This type of thinking persists in the conservative Christian community, and it begins to affect how they view other things. Just look at the followers of the MAGA movement, in particular Mike Lindell and his pronouncements that soon his lawyers will present information that will change everything about the 2020 election. He gives a date by which everything will change; that date comes; nothing changes; he grows silent; after a while, he gives a new date, and the cycle repeats. He’s been doing it for nearly two years now, and those who follow him and believe him give him a pass each and every time.

What can we make of this mentality? If nothing counts against a claim, then it’s not rational in any sense. Unfalsifiable claims are meaningless, and because they’re unfalsifiable, nothing counts against them. But in the case of prayer and the My Pillow guy, they have been falsified, time and time again, and yet believers hold fast. The belief itself, the faith itself, is more important, it seems, than truth.

Basketball Practice

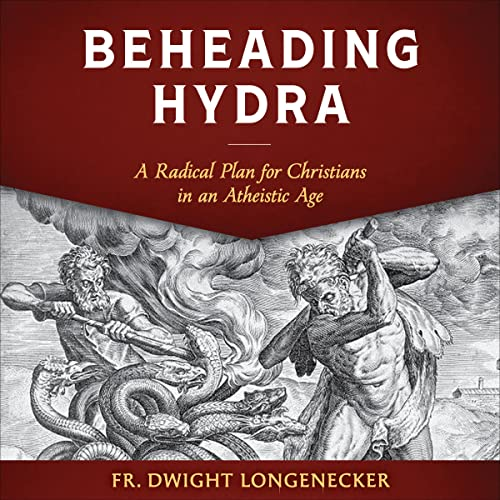

Beheading Hydra — A Review

Dwight Longenecker is the pastor of the parish we used to attend. He’s a prolific author, and the title of one of his books caught my attention: Beheading Hydra: A Radical Plan for Christians in an Atheistic Age. It purports to be a “radical plan” for believers in an age of atheism. As a once-Catholic-now-atheist, I thought it would be interesting to see how Longenecker defines the problem and what this radical solution might be.

The problem of what Longenecker seems to see as a predominately atheistic society is a “perfect storm” which is “the culmination of five hundred years of devious philosophies, half-truths, godless ideologies, false religions, and rebellion against God, his Church, and His timeless truths” (7). That’s quite a list of problems there, but what’s key to me is the five-hundred-year timeframe. What really began happening then? Modern science was slowly emerging from the mix of alchemy, philosophy, and superstition that had been used to explain the world in the past. The rise in atheism tracks closely to the success of the scientific method. Granted, what I’m suggesting here is one of the “-isms” that Longenecker claims is problematic, namely scientism, which is the claim “that science alone can render truth about the world and reality” (Source). I certainly don’t believe science is the only source of truth in our world, but when it comes to the physical world itself, it is certainly the most successful. Science continually knocks at religion’s door and says, “Here, we’ll explain that now,” whereas religion never offers explanations that supersede previously accepted science.

But the book is not about just scientism but a whole bunch of “-isms”

- atheism

- materialism

- historicism

- scientism

- utilitarianism

- pragmatism

- progressivism

- utopianism

- relativism

- indifferentism

- individualism

- tribalism

- sentimentalism

- romanticism

- eroticism

- Freudianism

That’s a whole lot of “-isms” to tackle in a book just a bit over 200 pages in length, but Longenecker plows through them all, explaining how they’re problematic for Christians and how they contribute to this “atheistic age” he sees us in.

But how can this be? How can we live in a largely atheistic society when most atheists point out the number of elected officials who are Christian is many times larger than the number of elected officials who are atheist (to use one simple metric)? It’s simple: “most atheists are blind to the fact that they are atheists” (21). I read that and immediately realized where he was heading: if you’re going to call yourself a Christian, you’d better act like a Christian and a Christian as I define it. He frames it by saying that this tide of atheism can be slowed with people living authentic Christian lives, but suffice it to say his definition of “atheist” would leave most atheists scratching their head.

“But I’m not an atheist!” I hear you say. Really? Then why do you live like one? If you do not pray, if you do not tithe, if you are living without a real relationship with God, then your belief in God is only a theory (144)

That’s the answer: prayer, tithing, and creating a close community.

While the book is not an effort to disprove these “-isms” definitively, he does take some time to point out what he sees as flaws in them. Regarding atheism and materialism, for example, he makes the argument that miracles “remind us that weird things happen,” and then gives us examples: “Friars float. Dead saints smell like flowers thirty years after they were buried. Seventy thousand people said they saw the sun spin and plummet to earth at Fatima” (30).

This short list he makes refers to

- St. Joseph Cupertino, who had “the gift of levitation” (27).

- St. Bernadette’s body, which smelled like flowers thirty years after her death.

- The appearance of Mary at Fatima.

Cupertino lived from 1603 to 1663: this was a time when people were burning witches, so that Longenecker takes these fanciful claims that he could levitate seriously suggests to me a naivety that I would not have expected. Bernadette’s body does indeed look lovely, but that’s because of the efforts of the faithful: she’s not that way naturally. And Fatima? It’s just as hard to take that seriously.

It’s easy to understand why Longenecker might willingly accept these things: “The spiritual person sees miracles–divine interruptions–all around him, and and through his everyday experience” (31). If you’re looking for it, you’ll find it. That might be advice he’s giving believers, but I think it’s a double-edged sword: when you go so far as to believe in 17th-century floating friars and someone else says, “Wait a minute,” you’re creating a crack in your belief system that doesn’t have to be there.

What are his suggestions for dealing with all these “-isms”? It’s to develop a “creatively subversive alternative.” Real Christianity. Deep Christianity. Prayerful Christianity. After all, it’s happened before: “Every five hundred years, there seems to be a major crisis in the Faith, and at each juncture, a new wave of witnesses rise up.” First there was ancient Rome, but “the first Christians simply lived a graced life of charity and peace, and the pagan world was drawn to their example and converted.” Then, in the sixth century, “St. Benedict stepped out and established simple communities centered on prayer, work, and reading,” which served as a bulwark against the “listless and corrupt” church. By 1000 CE, there was more corruption and crime but the “Benedictine Order surged forth in the great Cistercian renewal.” Finally, there was the Reformation and the Catholic Church’s Counter-Freformation which “brought renewal simply by living out the creatively subversive alternative” (133).

Yet Longenecker’s suggestion that this same kind of solution (returning to a prayerful traditional Christian life) will work in 2023 is almost laughably naive. The forces at work now are much more powerful than the forces at work in the previous periods, and they’re driven by one thing: the internet. Subversion and alternate views can reach even the most sheltered people now, and the amount of material available that simply picks at thread after thread in the tapestry of Christian belief is overwhelming. Skeptics have methodically taken apart argument after argument and shown how the arguments simply don’t make sense. They constitute an ever-present “yeah, but” to everything Christian apologists say, and no amount of praying is going to make that go away.

Really, the only answer is complete sequestration, and that is in essence what Longenecker is suggesting, and it’s what he was doing in the parish, and it’s a significant reason we left.

Final Party

We had a dinner party this evening with people we know entirely because of K. One couple was K’s former real estate clients. They hit it off well, to say the least. The other couple K knew because she worked with the husband in surveying years ago. And their daughter does K’s hair. (No one does my hair. Well, K makes sure I’ve shaved it well.)

And K made her first ever meringue.

Thus ends our Christmas break

Rainbow Falls

Short video from yesterday.