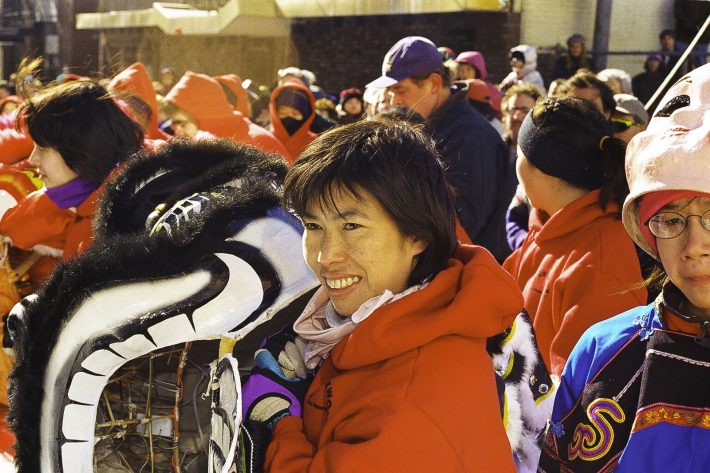

Twenty years ago this month, I headed to Chinatown in Boston on a Saturday morning with several coworkers to video, photograph, and interview participants in the community’s Chinese New Year celebration.

We were all working for Digital Learning Group, shortened to DLG in conversation, which would soon be rebranded DLI (Digital Learning Interactive), a company making interactive textbooks for college courses. This was 2000 — pre-social media, pre-almost-everything-we-call-the-internet-today. There was really innovative thinking behind that company, but we all seemed to be figuring it out as we went along.

I volunteered to take photos, and I didn’t even have a digital camera at the time. I took my Nikon FG, my best lense, and a lot of optimistic hope on that photoshoot.

My job had nothing to do with technology at that time, though. A graduate student in philosophy of religion, I’d been hired as the editor for the intro to religious studies book that was just under development.

At the time, I was studying at Boston University and writing things like this in my journal:

I’ve been reading Durkheim for class next week and I have to admit that he’s a little frustrating. I sometimes feel as if he takes me on great, circular arguments that assume points vital to that which he is trying to prove. For example, he talks about the fact that society needs an ideal to create itself (Elementary Forms of Religious Life 422), yet he’s not quite clear whence comes this ideal. He seems to indicate that it comes from the sacred/profane distinction, hinting at some kind of epiphany the believer experiences during some religious ritual. Yet whence comes the sacred/profane distinction? As I understand Durkheim, this comes from society. Yet religion, he indicates, in a way gives birth to society (418). In fact, religion and society are all but indistinguishable, yet he uses one to discuss/prove the other, and then a few pages later, the other to prove the first. It’s incredibly annoying.

We honestly really didn’t know how we were going to use the material: we had authors creating content for the sections on Islam, Christianity, and Judaism, but nothing for eastern religions.

The author for our Judaism section was Jacob Neusner, who sent in a 50+ page resume. At that time, he had 500 book publications to his name, and by the time he passed in 2016, had over 900 books published. How on earth did he do that? I wrote about it in my journal:

That seems completely impossible — five hundred books? I think he was born in the 30’s; finished his grad work in the 60’s. That gives him forty years of academic life. But let’s say he began writing as undergrad, when he was twenty. So that’s fifty years, which comes up to ten books a year, or a book every 36.5 days. That has got to be a slight misrepresentation; it has to include books he’s edited and such.

I can attest to the man’s speed: I was unable to keep up with editing his work while he wrote it. He sent in a new chapter every couple of days, and because I was working on a number of other projects, I was taking about a week per chapter.

I look back on that time, and I don’t recognize myself. I read my journal from that time — I was still writing daily — and I don’t see myself in my concerns. That’s always the case, I guess.

Still, I enjoyed working that job. I enjoyed being part of the .com explosion, of working on something that seemed so innovative.

Ultimately, though, I quit the job. Poland had sunk its hooks in me more deeply than I’d initially realized. I was getting letters from students (“Czy mogłabym pisac do Pana po polsku, bo wiem, że jak piszę po angielsku to robię dużo będów i Pan się może denerwuje czytając list z takimi bądami.”) and finding that I missed it all so terribly.

Plus, by then I’d moved to the tech side and was getting great money for essentially making a computer jump through hoops. I was learning much but accomplishing little, I felt.

Now, twenty years later, I’m back in America with a big slice of Poland here with me, teaching again, feeling like it was all so inevitable, this path I’ve taken.