Helping with Chores

Positive Reinforcement

It’s a struggle, working with a class of students that are such a mixed bag as some of my periods. Some have never really had much success in school, and they show it with their behavior. Some have never really learned basic social skills, and they show it with their behavior. Some desperately want to learn but struggle, and they show it with their behavior.

Many times, I’ve thought (and a few times even said) that I wish students could see them as I see them, to see their behavior issues as the problems they are, to see their future as I fear I see it unless they change. How to do that though?

“I’d give a whole month’s pay” begins one such little fantasy. Let them sit in my head, as in Being John Malkovich, but see what I see as I see it. But how to do that? It is of course impossible. The closest we could come would be a numerical representation of behaviors: you do this x times per lesson; you do that y times per lesson. Data, in other words. Yet how to get that data?

Enter: a perfect solution. A silly web site and app that are not so silly after all. I’d heard of classdojo.com before, but I’d only heard of it? Why hadn’t I simply loaded it into a browser, for when I did, I immediately saw the potential.

Numbers don’t lie. I might not catch all positive actions (and that’s what I really need to focus on for this to work), but I catch enough to make it meaningful. To make it count — literally now.

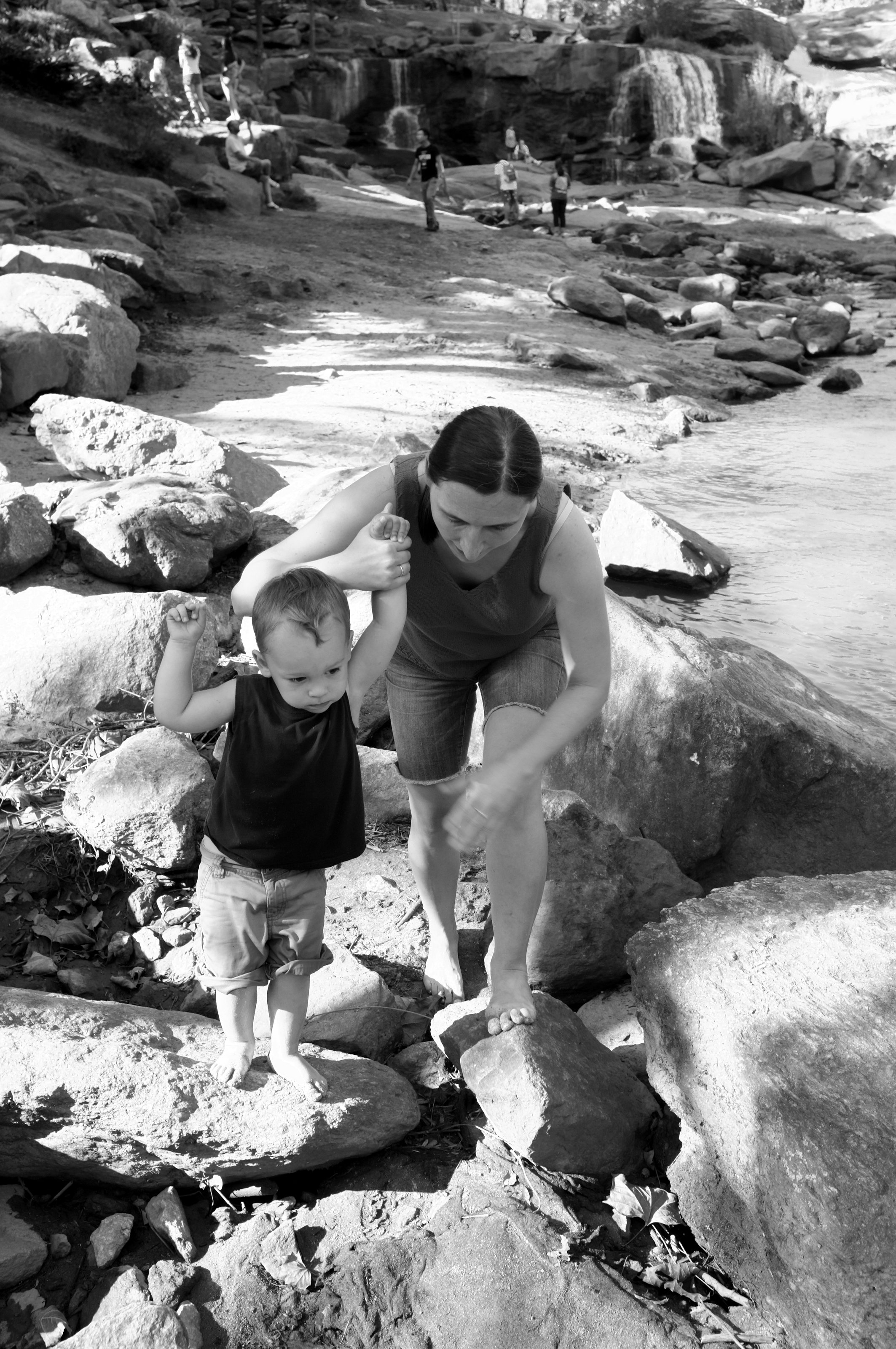

Nearly-Autumn Saturday

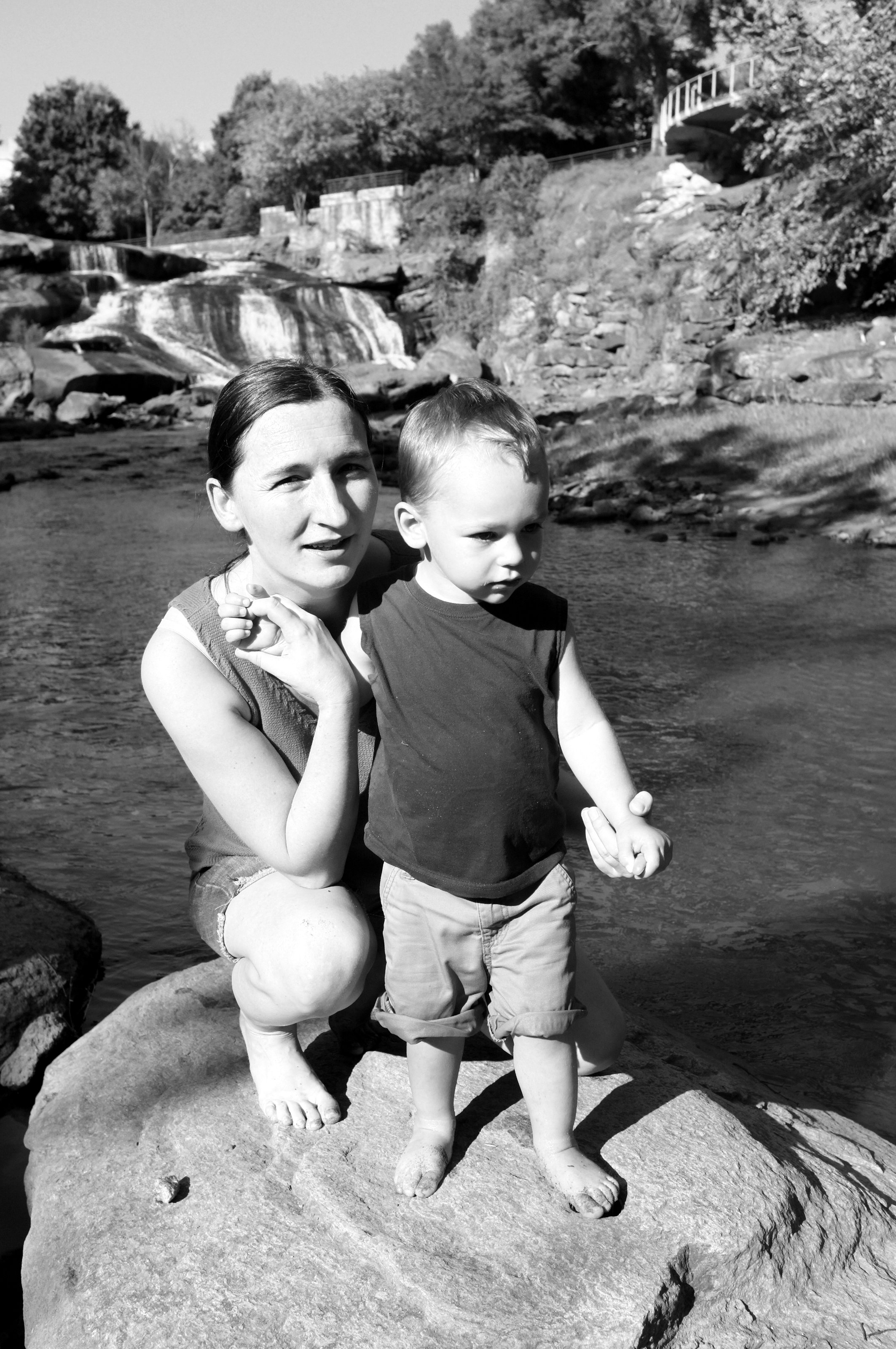

Friends from Asheville came down today. Friends? Well, almost family it seems. After all, M is E’s godmother, and that, according to M’s daughters, make them at least half cousins with L. We headed downtown for some ice cream at Marble Slab (where else?) and a walk around Falls Park, which included wading in the Reedy. There was also some duck feeding, but that nearly turned into disaster as the ducks grew braver and decided to go after E’s cookie as well as the crumbs we were tossing.

Back home, a first: Nana and Papa gave us a campfire ring some weeks (or was it months?) ago, and we finally put it to use, building a small fire in the backyard in our heretofore-unrealized holidy-motif fire ring.

It just seemed right to have our inaugural bonfire with a group of Poles.

Graham Crackers

Fast Forward

Sometimes it seems life with the Boy and the Girl is on fast forward. This is especially true of the Boy, now that he’s talking and giving us more than the mere glimpses we used to get into his developing intelligence and personality. This morning, as I was preparing coffee to take to work, I hear,

“Daddy, can I try it?”

It’s a common refrain: the Boy wants to try everything. In that sense, he’s the polar opposite of L, who hates to try anything new.

“No, little man, this is coffee. It’s hot, and it’s got caffeine. You’re too young to drink it.”

He thought for a little while, then asked hesitatingly, as he often does when he’s turning something over in his thoughts as he speak, “But when I’m bigger?”

Fast forward to the post-dinner cleanup. K was talking to the Boy and for some reason — some of those little conversations start so harmlessly insignificantly that it’s difficult to recreate them in the evening — said something like “B, as in bottle, as in big, as in…” At which point the Boy took over, with boy, baby, and a few others.

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

I was recently asked to view this TED talk and provide some feedback. Here’s the talk.

Here are my thoughts in virtually un-edited form:

To begin with, a few seemingly-random facts: Sir Ken Robinson has a PhD from the University of London. He’s speaking as part of the TED program, which was implemented by Chris Anderson, an Oxford graduate, and his Sapling Foundation. This video was delivered on the World Wide Web, which, despite Al Gore’s protests to the contrary, was the creation of Sir Timothy John Berners-Lee, who studied at Queen’s College at Oxford. All of this is computer based, and many attribute the creation of the computer largely to John von Neumann, a classically trained Hungarian mathematician and physicist who, in an effort to bring himself some peace on his deathbed, quoted from memory large swaths of classical poetry in their original Greek and Latin. I am currently writing this on a computer in my home that uses Linux, an operating system (i.e., Windows and Apple’s OS X) created by Linus Torvald while he studied at University of Helsinki. While many might never have heard of it, Linux is the most used operating system in the world, running on 80% of the world’s super-computers and probably closer to 95% of the servers that make up the Internet. Finally, I am writing this in a country that in the history of the world is and has always been quite unique for its constitutional freedoms, a country that was created by a group of men that experience classical education in its truest meaning.

So it’s deeply ironic that Robinson and all of the individuals who created the technology to view his speech were products of this very education system that Robinson suggests needs reforming. Robinson suggests that we’re stifling innovation and thus we need to have a revolution in education but he says so on a platform made possible by this age of unprecedented innovation, an age that is the product almost exclusively of classical education and its modern kissing cousins.

Robinson suggests that modern education is killing creativity. Yet to be creative, one must have something to be creative with. Otherwise, creativity consists of only the basest instincts, as we have seen here at Hughes on the eighth-grade hall with the recent behavior of two of our students. Their hideous act (and if you don’t know what it was, it’s best not to ask), in their eyes, was brilliantly creative. But as the saying goes, garbage in, garbage out. If we start with nothing to be creative with, we will be creative with our basest instincts.

We traditionalists often suggest that we need to have a wide liberal arts education before the specialization of college in order to ensure the continuation of culture, but it is less esoteric than that. Creativity comes from having something to create with, and all great creative endeavors have stood on the shoulders of the creativity of others–I know I’m mixing my metaphors here, but I’m only intending a first draft of this, so bear with me. Picasso, for example, did not start with Cubism; he learned all the rules, then he decided how he wanted to break them. Faulkner did not begin by writing run-on sentences; he mastered his craft and then learned how and when to break the rules for effect. Linus Torvalds did not create the Linux operating system in a vacuum, and Jef Raskin, Bill Atkinson, Burrell Smith, and Steve Jobs did not create Apple’s operating system from nothing: they both used UNIX, an older, very stable system, as a starting point. So when we start pushing this individualization, this specialization from graduate school to college to high school to middle school, we decrease the amount of raw materials we provide students to be creative with. Despite Robinson’s contention to the contrary, it is based on “the idea of linearity.”

The truth of the matter is that education is linear: one has to learn addition before algebra, and one has to learn algebra before calculus. One has to learn to read music before embarking on a Chopin Ballade. One has to learn basic coding before attempting to create an operating system. There is a hierarchy of knowledge in any discipline, and one must learn things in that hierarchical order or else it’s simply chaos.

I understand Robinson would not dispute that. He’s not suggesting we let students begin wherever they want. He’s talking about an organic model that allows students to follow their own interests wherever they lead them. To do otherwise, he suggests, is soul-killing: We “have sold ourselves into a fast food model of education, and it’s impoverishing our spirit and our energies as much as fast food is depleting our physical bodies,” says the man who quotes Yeats, a product of this very education, an education that, in Yeats’s time, was much more linear than anything we have today. My point is that, as with creativity, to be organic, you have to start with something: life, art, technology, or even existence does not start from nothing.

But there’s more to it than that when we consider the fact that we live in a democratic republic like America. Robinson suggests that students should be able to create learn “with external support based on a personalized curriculum.” This is going to result in a highly fragmented society, with very little common knowledge–i.e., cultural literacy–to share. It is nothing short of Balkanization. E. D. Hirsh, Jr. writes in Cultural Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know about the impact of highly-specialized knowledge on democracy:

No modern society can hope to become a just society without a high level of universal literacy. Putting aside for the moment the practical argument about the economic uses of literacy, we can contemplate the even more basic principle that underlies our national system of education in the first place–that people in a democracy can be entrusted to decide all important matters for themselves because they can deliberate and communicate with one another. (12)

In other words, for democracy to work, everyone must be informed about the basic issues and be conversant about them. That this is not the case in America today is painfully obvious when watching the gotcha viral videos that show people struggling to name one single American senator, to find a given country on the map, and other ridiculous ignorance. Should we create a completely personalize curriculum, many of our students would study video gaming and rap music, leaving very few who are interested in the functions and institutions of our government. It’s easy to see that this becomes an oligarchy quite quickly.

So Robinson can’t possibly be suggesting complete topical freedom for students. He would have to accept the fact that there are some basic things that everyone needs to know in order to function in a modern Western democratic society, but the instant he does that, he’s undermined his own argument. What we have them is not the revolution Robinson is claiming but a bit of feel-good tinkering around the edges. Or complete chaos.

What then is the problem? Why does our education system not work anymore? I suggest that it’s not the education system that’s broken: after all, as I pointed out, it has created all we see around us today. It’s culture that’s broken. Why does the same educational system of the early 20th century no longer work? Because it doesn’t mesh with the 21st century culture, which demands instant gratification, complete and blissful entertainment, and absolutely no hard work.

Furthermore, education doesn’t kill creativity; our modern culture kills creativity. We turn on and tune out with our huge televisions, mobile devices, and gaming systems, then wonder why we aren’t as creative as we used to be. We serve up to our children mindless entertainment that requires no imagination, then wonder why they don’t have imagination. And like always, we blame it on our education system, the system that created Mark Zuckerberg and Sean Parker, Sergey Brin and Larry Page, Bill Gates and Steve Jobs. And what do most people use these men’s amazing inventions to do? Foster creativity? Hardly.

So can this proposed Robinsonian revolution solve the problem? Well, I don’t think as Robinson presents it, it really is much of a revolution. A total revolution would look like this: the dissolution of the grade-level system in exchange for a mastery-learning program with a basic curriculum that fosters general civic, mathematical, linguistic, scientific, and technological literacy. This program would let students learn these basics at their own pace, but it would require mastery before moving on. If takes a student three years for one topic in math, then it takes that student three years and she stays there until she shows mastery; if it takes another student three months, that student moves on in three months. Once students master these basics–what used to be about an eighth-grade education but now is probably more like a twelfth-grade education–students can move on in a similar setting to explore any interest he or she wants. And if that means a student stops his education then and gets a job in construction, then that’s his choice. But that is too radical a reform, and still more important to policy makers, the fiscal cost of such an education would be relatively staggering.

Yet that wouldn’t solve the underlying cultural problem. That, I’m afraid, is out of the purview of public education. It’s a pessimistic view, I understand, and I’m sure some might wonder how I could be a teacher with such a bleak outlook.

And so in final response to Robinson and to more succinctly and beautifully sum up my thoughts, I too turn to Yeats:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

The Boy and His Papa

The Sign of the Cross

We’re starting simple, with the most basic prayer there is: the Sign of the Cross.

The Boy’s getting it. Sort of.

The First Battle of the Marne

They don’t know what awaits they, but by now, they realize it’s not what they thought it would be.

Peace

I often wonder just how much peace my students experience at home. It seems to be an inverse relationship: the more troubled the behavior, the less peaceful the home. A colleague tells of a home visit that sounds absolutely horrifying: two loud televisions in one room, one with sports and the other with some movie, a loud boom box in a nearby room, someone sticking his head in to yell “When’s dinner?!”, and all the while, the conversation continues about the student’s performance and not once does an adult offer to turn down any of the noise.

“They’re surrounded by noise, by motion, by stimulation,” another colleague mentions during lunch. “It’s no wonder they can’t sit still, can’t focus.”

Not to mention what they consume in the name of food.

I have a rough class before lunch, and when we return from lunch, twenty minutes remain until the next class change. I work on social skills with them; I let them relax a while if they’ve worked well during class time; but most often, I try to give them peace. I turn the lights off, instruct them to put their heads down — why is it they won’t put their heads down when told but at least one every day wants to put her head down during class time? — and simply stop. Stop moving, stop talking, stop shaking a leg or beating a finger on the desk. Just stop. Take a moment to collect themselves.

Most of them can’t do it.

I try to play soft music for them, but I wonder if, obsessed as they are with rap “music,” the classical music I play for them might be exhausting. They might not even know what a melody is, and if that’s the case, they can’t find much pleasure in classical music. Add to it their painfully short attention spans and it becomes rather obvious that they can’t trace out the development of a musical theme, let alone notice when it repeats and begins morphing as it does in Romantic and Classical (as in the period, not the genre) music. I find Haydn works best, better than just about anything else.

Fast forward a couple of hours. K, E, and I have dinner together. What a blessing just to have dinner together. What a blessing that the Boy loves veggies. What a blessing that we had an entire zucchini to feed him.

After dinner, we go to the newly-paved street across from our house. K rides the scooter; the Boy coasts around on his whatever-it’s-called. They bump each other, chase each other, goof around. I take the pictures.

After riding, Nana and Papa bring the Girl back and everyone sits a while and talks, rides bikes, fusses, cries, laughs.

After bath, after snacks, the kids lie on the bed with K who reads a new book from the library, translating the English to Polish to provide the kids with more exposure to the language.

“Co to jest ‘snooty’?”

“Go with snobby,” I say.

What do all these vignettes have in common? A peace that comes with a family spending time as a family. A peace that I’m not sure some of my students can even imagine.

Everyone Gets a Turn

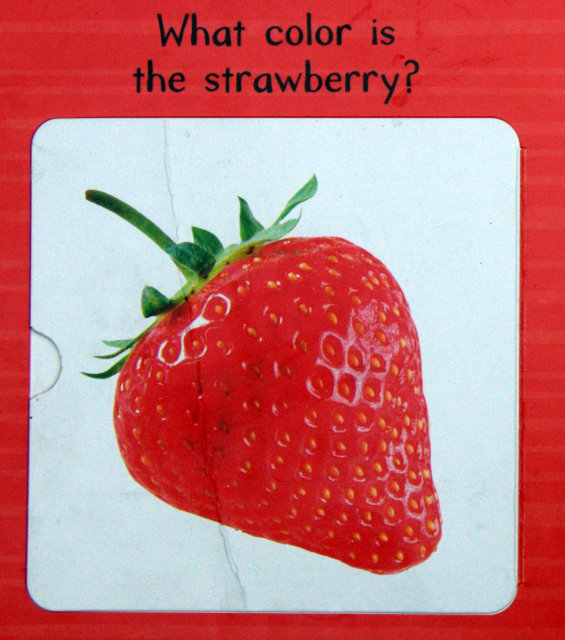

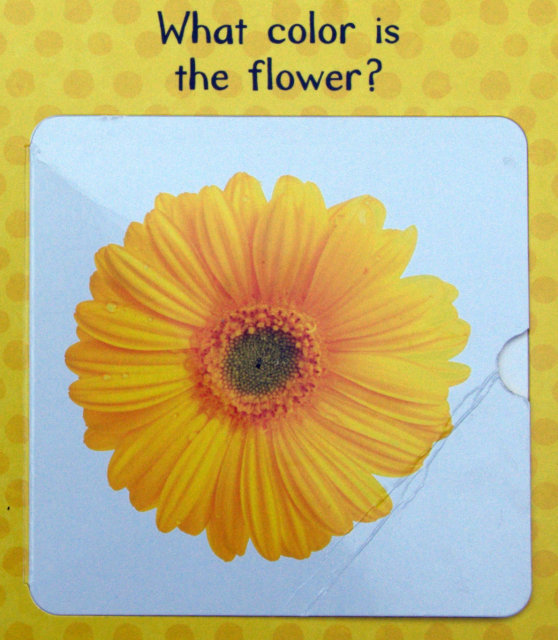

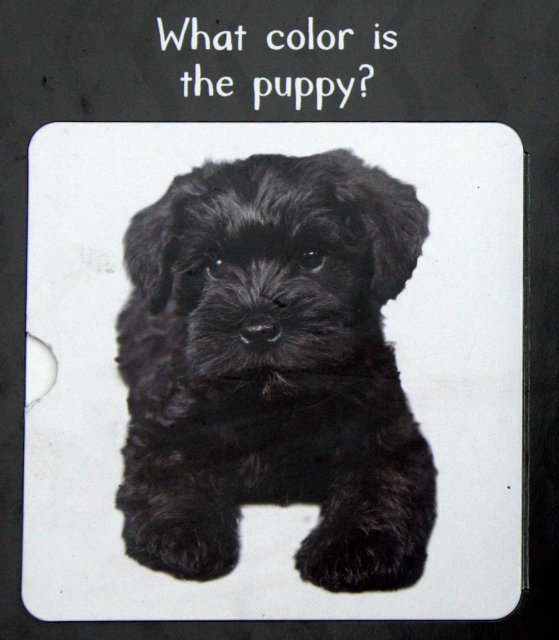

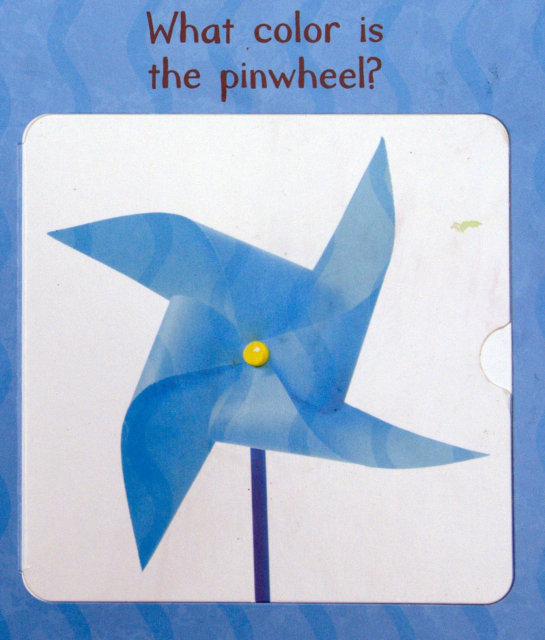

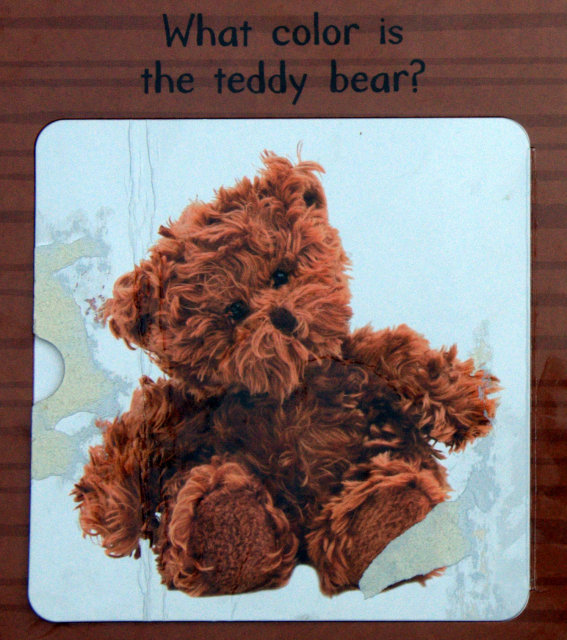

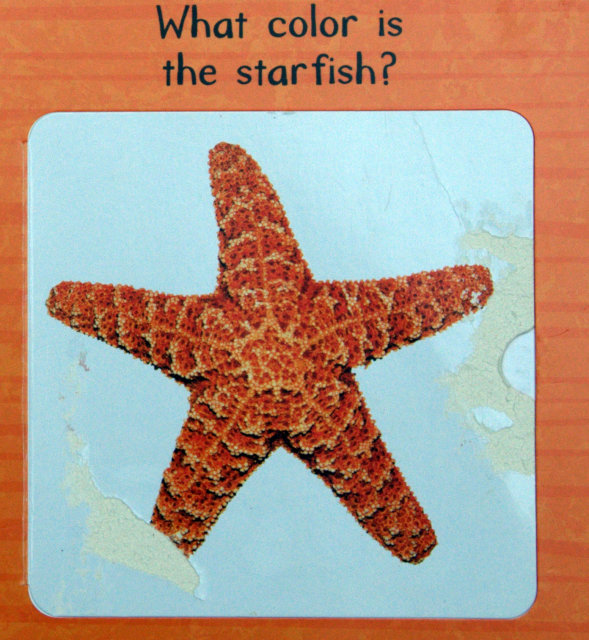

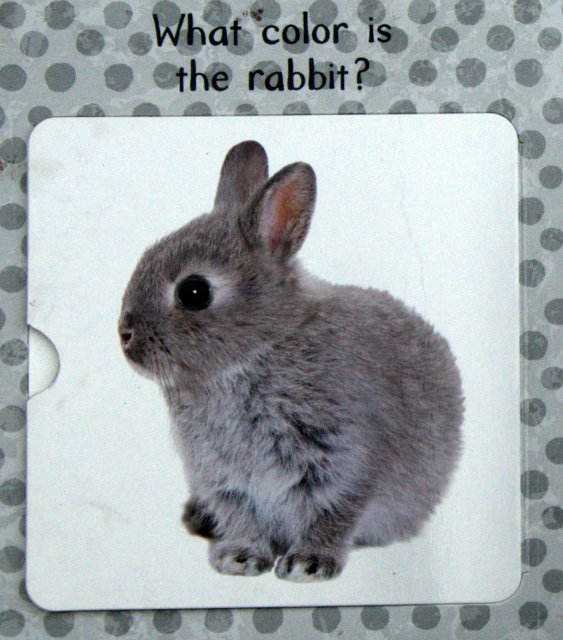

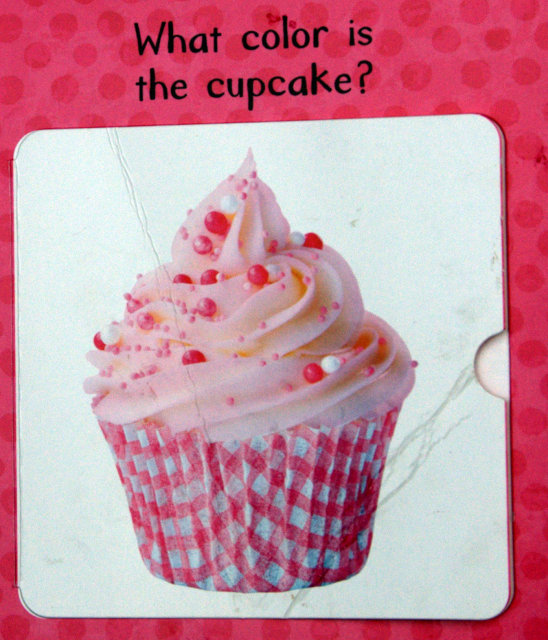

Colors

Sometimes, the Boy tries to be cute. He sees the camera out and decides to scrunch up his face into a silly expression. But sometimes, it seems to come more naturally. And sometimes, it’s positively eerie — in a positive way, of course.

Today, while sitting on the bed waiting for the girls to get ready so the three of them could head to a friend’s for a birthday party, E and I decided to read a book. And he selected his new favorite, a book on colors from the library. He knows red. He wants to know them all. But he knows red.

We began.

Pointing to the strawberry, he said, “Red!” No hesitation. We turned to the next page.

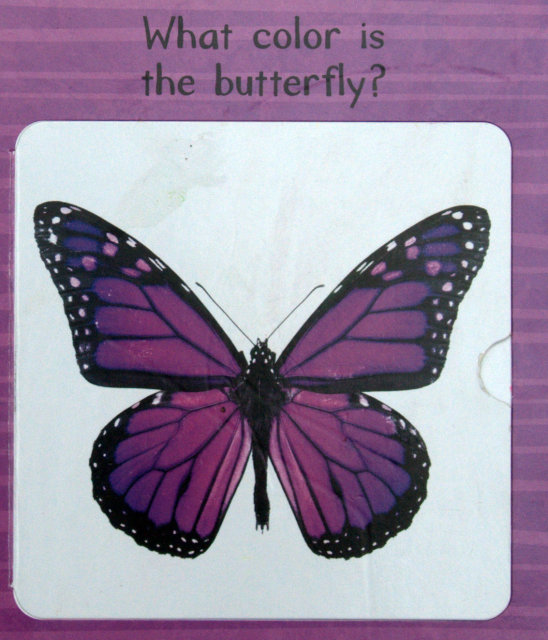

E was a bit hesitant, but wanted to do well.

“Um, red?”

“No, purple.”

“Urple?”

“Yes. Purple.” And we turned the page.

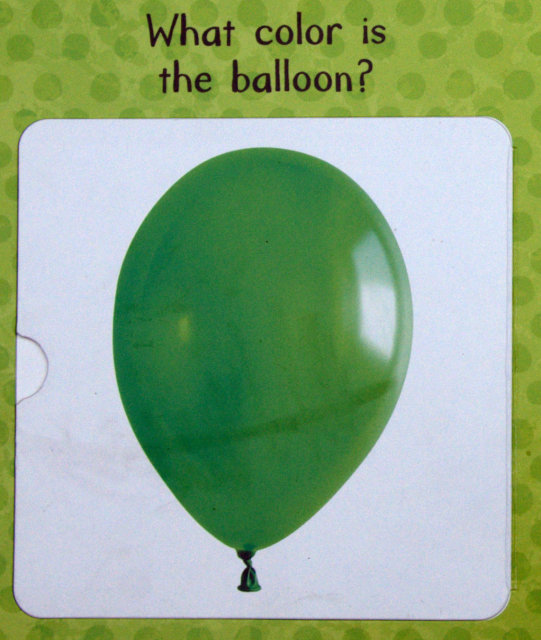

“Um, red?”

“No, buddy, it’s green.”

“Green?” And we turned the page.

“Um, red?”

I started wondering at this point if it was a game. He does like to be silly. Still, I played along, game or no.

“No, little man, it’s yellow.”

Next page.

“Um, red?”

I realized at this point that perhaps he doesn’t know red. Perhaps it’s the only color name he knows.

He knows blue. He’s used the word before, and correctly. I was expecting “Um, blue?”

“Um, red?”

No, he doesn’t know red. Or blue. Or yellow. Or green. He doesn’t know his colors.

We turned the page.

“Um, red?”

We turned the page.

“Um, red?”

“It’s not funny anymore,” I wanted to say, even though it was.

Yep — red.

We turned to the final page. Pink. Close to red. “Red” would be a close enough answer, especially to a colorblind daddy like me.

“Um, yummy!”

No, it wasn’t a game, but it sure seemed like a set-up.

Saturday

Keeping Me In Line

Cleaning the floor is a delicate matter. Use this on this surface; use that on that surface. I was using the wrong this on the wrong that, and when K returned from shopping with the Boy tonight, she informed me in no uncertain terms that I was not to be using this with that. The Boy was standing and watching. When K walked away, he was kind enough to make sure I understood it perfectly:

“No, Tata, no!” he said, finger wagging. “Don’t use this here. No Tata!”

Boot Heel

Dear Terrence,

Today was it. I do honestly like you all; I do honestly believe in your abilities and your intelligence; I do honestly see in you potential. But you all don’t see it in yourself, and because of that, you disrupt. Constantly. We’ve been in school three weeks now, and you’ve shown me that when given the chance to act like adults, you act like infants: you fuss about infantile things, you laugh uproariously and chaotically about infantile things; you fight over infantile things; you talk constantly about infantile things. You’ve shown me you’re just not ready to be treated like adults. What this means is that I must treat you like children. I must seem harsh in order to protect you, from yourselves and from your self-destructive habits. And so tomorrow, though I don’t really want to, I will be putting my foot down. That’s a cliche that doesn’t really adequately explain just how hard I’m going to hit you all tomorrow, so to speak. I expect to send at least ten students – that’s fully one third of you – to the assistant principal for being disruptive, because I’m going to define “disruptive” in such a harsh way that sneezing might get you sent from the room. I do this because you can’t handle the slightest amount of freedom: one off-hand comment to a peer turns into complete chaos in the class in a matter of seconds. One giggle sets ten others giggling. You are lemmings, robots – your behavior is so predictable. And so I am going to make my behavior equally predictable.

Today was it. I do honestly like you all; I do honestly believe in your abilities and your intelligence; I do honestly see in you potential. But you all don’t see it in yourself, and because of that, you disrupt. Constantly. We’ve been in school three weeks now, and you’ve shown me that when given the chance to act like adults, you act like infants: you fuss about infantile things, you laugh uproariously and chaotically about infantile things; you fight over infantile things; you talk constantly about infantile things. You’ve shown me you’re just not ready to be treated like adults. What this means is that I must treat you like children. I must seem harsh in order to protect you, from yourselves and from your self-destructive habits. And so tomorrow, though I don’t really want to, I will be putting my foot down. That’s a cliche that doesn’t really adequately explain just how hard I’m going to hit you all tomorrow, so to speak. I expect to send at least ten students – that’s fully one third of you – to the assistant principal for being disruptive, because I’m going to define “disruptive” in such a harsh way that sneezing might get you sent from the room. I do this because you can’t handle the slightest amount of freedom: one off-hand comment to a peer turns into complete chaos in the class in a matter of seconds. One giggle sets ten others giggling. You are lemmings, robots – your behavior is so predictable. And so I am going to make my behavior equally predictable.

I expect to get calls from parents. I expect to see frustrated students. But I’m doing it for one reason: I will not let you screw up your own education because you find everything else in your tragic world more important.

So take a deep breath, and hope for a change in everyone else soon, because you can only change yourself, no one else. And until you do, all privileges in my classroom are indefinitely suspended. I know it sounds like I’m angry when I say this, and I am, but I’m not doing this to make my life easier or to torture you: I’m doing it to protect you.

Tying my boot laces already,

Your Teacher

Echoes

The Boy is in bed, trying to fall asleep. The cat jumps onto the bed and begins pestering the Boy, who stands up and says, “No, Bida!” When the cat doesn’t listen, the Boy says sternly, “When I say ‘No,’ I mean ‘No.'”

Guest

He was hanging in a web spun between the handrails on our deck, an enormous guest whose body was probably two inches long, the span of his legs much longer still. He was impressive size, impressive color — and probably impressive eater as well. I didn’t know what kind of spider it was; I doubted it was dangerous, for only black widows and brown recluses are spiders of venomous note around here, and this fellow clearly wasn’t either. Still, a bite would probably be painful, especially for a child. So I did the logical: I gently knocked the web down, then pushed it off the deck.

Will he return tomorrow?