Having children necessitates it, one would think. Perhaps they’re not so much necessary as inevitable, for even the worst parents I would imagine fall into some kind of routine partially dictated by their children, even it if it is simply to neglect them cruelly. That of course is not our story. Our family runs on routines, pure and simple. We don’t even question them; the only question is who will do what, and habit has largely answered that question for us. There are morning routines: the Boy, for instance, must — simply must — have his Cheerios before all else. He will insist on wearing a soggy diaper from the full night’s sleep if there’s any question of putting him on the potty chair before his first bowl of Cheerios. As for the Girl, she has to have a blanket wrapped around her to keep off the morning chill, even when it’s summer and there is no morning chill. There are afternoon routines involving snacks. There are the standard evening routines, who puts which child to bed, who supervises the bath, who straighten’s up the day’s messes. There are travel routines, fussing routines, play routines, shoe routines, bathroom routines. We even fall into meal preparation routines.

The thought of abandoning all those routines for a weekend would be tantamount to suggesting that we try not to breathe through all of Thursday morning or not get up on a November Monday morning. And yet, in celebration of ten years of marriage, we decided, with a little help from Nana and Papa, to drop all the routines and just breath for a weekend.

A small cabin on the banks of the French Broad River in Hot Springs, North Carolina (Population, according to one resident, about “Oh, I don’t know, six-twenty, six-thirty”) was just the place to do just that. To walk on the banks of the river,

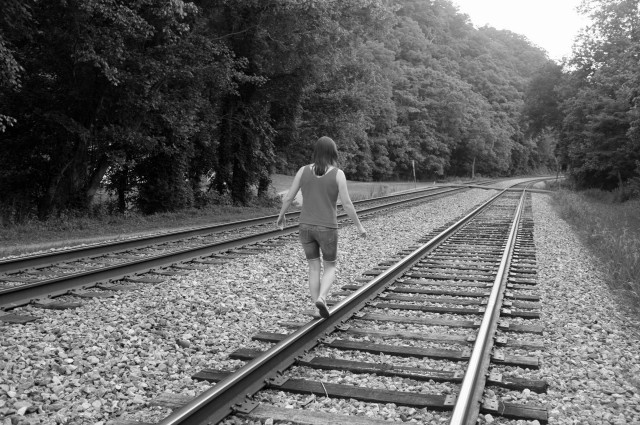

to stroll by the railroad tracks looking for spikes to take home to our train-obsessed little boy.

This was the plan. And this was, it seemed, what all the stars in the heavens aligned against — if one believes in such things — as we tried to make our way there. First, there was the flood. It was supposed to keep raining all weekend, and Friday morning at four, as I was trying desperately to keep the water from spilling from the storage half of the basement to the living half of the basement, it seemed unlikely that we would be able to make it.

On the way to the cabin — about a two-hour drive — we encountered an accident in the road that stopped traffic from going both directions. Not an insurmountable obstacle, but we both joked about it. After a few minutes of waiting and checking the GPS for alternate routes, we decided to try what so many other cars were trying and do a U-turn in the median. We got all four wheels in the median, wet with two days’ rain, and the front wheels started spinning. Visions of what it might take to get us out were just forming as I shifted into reverse, caught enough traction to back up to the pavement, then tried again, successfully, after gaining a bit more momentum. Three efforts to stop us, all failed. Still, what else might be waiting, we wondered.

Granted, an incredible, modern cabin made from wood of a hundred-year-old cabin brought from deep in the mountains awaited us. A cabin so perfect that we found ourselves saying things like, “This is what we need we retire.”

That little slice of perfection waited, but there were a few more obstacles first. Like being unable to find the cabin despite following instructions that matched both the GPS’s monotone directions and Google Maps. When you head down a narrow mountain road that soon becomes a gravel road, which crosses a railroad track — all according to direction — and leads to an enormous abandoned house that looks like something from the horror story William Faulkner never wrote (granted, from a certain point of view, that’s all he wrote, but that’s another literary argument). When you get through all this and overcome the visions of mindless zombie hordes flooding out of the abandoned structure and manage to pull away, when you make it this far and decide that, despite the late hour, you must call the owner, there’s only one possible outcome: no bars. None. T-Mobile has been the object of my hatred and vitriol from the start (why did we switch? but that’s another horror story), but now my hatred became white-hot. We drive back to town, found an open shop, and asked for directions.

“I know where the road is,” the attendant said, “but I don’t know that exact address.” He looked back at the slip of paper I’d given him and then said, “Come on.” We went out to the young man sitting in front of the store and the attendant asked, “Hey, do you know where Harold has his cabins?” Small town — they know the owner by name. We didn’t yet know just how small and just how inevitable such an exchange would be.

He gave me directions; I replied, “That’s where we went.”

“Yeah, but you’ve got to turn before the tracks. Did you see that little gravel road beside the tracks?”

We had indeed seen that road, and started down it before deciding it couldn’t be right.

And so back we went, down the the rail-side tracks on a road that came so close to the tracks that my heart thumped when K asked, “Can you imagine being at this point of the road when the train comes?”

We later shared this with the owner. “Oh, I do that on purpose. It’s quite a rush.”

But finally, we’d made it. Everything faded away as we slipped into the hot tub on the front porch, listened to the crickets and cicadas, and marveled at how utterly dark it was in that secluded place. The stars provided enough light to see the clouds passing by overhead.

Next morning, we headed to town after a short walk along the tracks, surprised at how quickly and effortlessly we’d made it through the transitions. No kids to feed; no E to worry about potty training; no L to worry about moments of panic exaggeration; no car to pack. We simply ate our breakfast, took our walk, and said, “Well, let’s just go head to town.”

We had a relaxed lunch without fussing about food this one doesn’t like or about getting more of this or that food that the other is on the verge of breakdown about. No trips to the bathroom afterward to clean an incredibly independent but not quite coordinated little boy’s enthusiastic eating.

We just ate lunch, paid the bill, and left. No routine.

“What a marvelous change,” K said. Or was that I who said it? Or both?

We headed over to the grounds where the Bluff Mountain Festival is usually held, trying to place where the stage was, where we usually sat, where the clogging area was — mindless chatter.

We went to the hot springs for which the town is named, soaking in a hot tub filled with hot mineral water that made our skin tingle and our muscles relax. We went on a short kayak trip with no one panicking at the rough water (L) and no one begging for more (E).

We went for another walk when we got back to the cabin,

talked about how thrilled E would have been to be standing there as a train crawled by then stopped, waiting on the siding for an opposite-bound train to pass by and stop to wait for a third train to go by.

There was no one to complain about how long our by-the-train photo session was taking.

There was no one to ask just how many times we would take the same picture.

There was no one to be utterly thrilled with the multiple deer sightings.

There was no one to complain about hunger when we returned to the cabin, no one to get upset about us going back into a hot tub for the third time in twenty-four hours, noone to put to bed.

In other words, it was absolutely and blissfully peaceful while being all wrong. Those routines, new and old, are what make us a family, and being a family is what makes us us. We are greater than the sum of our parts, and we are less than two individuals when we’re alone.

So when we got back to Nana’s and Papa’s and took the kids swimming, it was all as it had been before. The routines returned; the exhaustion of a return to the everyday settled.

And we were happily complete again.