Ten or so years ago, while preparing for the GRE in Poland, I was getting frustrated with the analytical section and how rushed I felt during the practice tests. One evening, I sat down with a cup of coffee and no timing device whatsoever, and I took a practice analytical section — and completed it without a single mistake. It took me almost twice the usually allotted time for the section.

When I took the actual GRE, my analytical results were substantially lower than the perfect score of 800. I attributed this solely to time pressure, and included a note in my grad school applications to that effect: “This test, I feel, was a test not of my analytical ability, but my ability to work under artificial time restraints,” I wrote, or something similar.

Yesterday, while taking ETS’s “Principles of Learning and Teaching, Grades 7-12” Praxis test, I found my mind returning to those long-forgotten themes.

What is the point of a time limit on a professional test? I understand that the administrators don’t want examinees to be there all day, but what is the thinking behind making the time so incredibly short that everyone is frantically working up until the moment time is called?

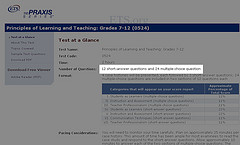

The PLT test consists of twelve short-answer questions and twenty-four multiple-choice questions. Or, as it’s put on their web site: “12 short-answer questions and 24 multiple-choice question” (my emphasis added). Those twelve “short answer” questions are divided into four scenarios, with each one having a long case history.

Here’s a sample, provided by ETS:

Case History: 7-12

Directions: The case history is followed by two short-answer questions.

Mr. Payton

Scenario

Mr. Payton teaches world history to a class of thirty heterogeneously grouped students ages fourteen to sixteen. He is working with his supervisor, planning for his self-evaluation to be completed in the spring. At the beginning of the third week of school, he begins gathering material that might be helpful for the self-evaluation. He has selected one class and three students from this class to focus on.

Mr. Payton’s first impression of the three students

Jimmy has attended school in the district for ten years. He repeated fifth and seventh grades. Two years older than most of the other students in class and having failed twice, Jimmy is neither dejected nor hostile. He is an outgoing boy who, on the first day of class, offered to help me with “the young kids” in the class. He said, “Don’t worry about me remembering a lot of dates and stuff. I know it’s going to be hard, and I’ll probably flunk again anyway, so don’t spend your time thinking about me.”

Burns is a highly motivated student who comes from a family of world travelers. He has been to Europe and Asia. These experiences have influenced his career choice, international law. He appears quiet and serious. He has done extremely well on written assignments and appears to prefer to work alone or with one or two equally bright, motivated students. He has a childhood friend, one of the slowest students in the class.

Pauline is a withdrawn student whose grades for the previous two years have been mostly C’s and D’s. Although Pauline displays no behavior problems when left alone, she appears not to be popular with the other students. She often stares out the window when she should be working. When I speak to Pauline about completing assignments, she becomes hostile. She has completed few of the assignments so far with any success. When I spoke to her counselor, Pauline yelled at me, “Now I’m in trouble with my counselor too, all because you couldn’t keep your mouth shut!”

Mr. Payton’s initial self-analysis, written for his supervisor

I attend workshops whenever I can and consider myself a creative teacher. I often divide the students into groups for cooperative projects, but they fall apart and are far from “cooperative.” The better-performing students, like Burns, complain about the groups, claiming that small-group work is boring and that they learn more working alone or with students like themselves. I try to stimulate all the students’ interest through class discussions. In these discussions, the high-achieving students seem more interested in impressing me than in listening and responding to what other students have to say. The low-achieving students seem content to be silent. Although I try most of the strategies I learn in workshops, I usually find myself returning to a modified lecture and the textbook as my instructional mainstays.

Background information on lesson to be observed by supervisor

Goals:

- To introduce students to important facts and theories about Catherine the Great

- To link students’ textbook reading to other sources of information

- To give students practice in combining information from written and oral material

- To give students experience in note taking

I assigned a chapter on Catherine the Great in the textbook as homework on Tuesday. Students are to take notes on their reading. I gave Jimmy a book on Catherine the Great with a narrative treatment rather than the factual approach taken by the textbook. I told him the only important date is the date Catherine began her reign. The book has more pictures and somewhat larger print than the textbook.

I made no adaptation for Burns, since he’s doing fine. I offered to create a study guide for Pauline, but she angrily said not to bother. I hope that Wednesday’s lecture will make up for any difficulties she might experience in reading the textbook.

Supervisor’s notes on Wednesday’s lesson

Mr. Payton gives a lecture on Catherine the Great. First he says, “It is important that you take careful notes because I will be including information that is not contained in the chapter you read as homework last night. The test I will give on Friday will include both the lecture and the textbook information.”

He tape records the lecture to supplement Pauline’s notes but does not tell Pauline about the tape until the period is over because he wants her to do the best note taking she can manage. During the lecture, he speaks slowly, watching the class as they take notes. In addition, he walks about the classroom and glances at the students’ notes.

Mr. Payton’s follow-up and reflection

Tomorrow the students will use the class period to study for the test. I will offer Pauline earphones to listen to the tape-recorded lecture. On Friday, we will have a short-answer and essay test covering the week’s work.

Class notes seem incomplete and inaccurate, and I’m not satisfied with this test as an assessment of student performance. Is that a fair measure of all they do?

From this, examinees answer three questions. They’re called “short answer” questions, but they’re really essay questions if one wants to answer the question carefully and thoroughly.

Question One

In his self-analysis, Mr. Payton says that the better-performing students say small-group work is boring and that they learn more working alone or only with students like themselves. Assume that Mr. Payton wants to continue using cooperative learning groups because he believes they have value for all students.

- Describe TWO strategies he could use to address the concerns of the students who have complained.

- Explain how each strategy suggested could provide an opportunity to improve the functioning of cooperative learning groups. Base your response on principles of effective instructional strategies.

Question Two

In the introduction to the lesson to be observed, Mr. Payton briefly mentions the modification he has or has not made for some students. Review his comments about modifications for Jimmy and Burns.

- For each of these two students, describe ONE different way Mr. Payton might have provided a modification to offer a better learning situation for each.

- Explain how each modification could offer a better learning situation. Base your explanation on principles of varied instruction for different kinds of learners.

There are two sample questions provided at ETS’s web site; on the actual test, there are three questions, each one asking for two specific examples of this or that. For each case-history essay section (like the one above, though with one more question), ETS allotted twenty-five minutes.

This might be fine if the case histories didn’t sometimes require multiple readings:

- trying to figure out things like whether Bobby is in the first group of students Mr. Tadeusz spoke with or the second group;

- wondering about the nature of the student-teacher relationship and prior interventions in a question about dealing with a disruptive student; or,

- fighting the urge to scream, “This test is ridiculous!”

Teaching is a reflective task, and often one’s first response to a situation is not the correct one. It leads me to believe that this test is only about testing how ingrained standard “first responses” are and nothing more. Indeed, any test with a severely restrictive time limit can only be testing how quickly examinees can recall and synthesize information.

One positive emerged from it all: I need to be more aware of how much time I’m giving my own students for tests and exams.

To its credit, South Carolina does not impose a time limit on its main standards-assessing test, the PASS (Palmetto Assessment of State Standard).