M and I were the most unlikely of friends. In many ways, we were as opposite as anyone could imagine. He was raised by his grandparents in the country, and throughout his schooling, I’m sure he was considered “at-risk.” He smoked (cigarettes and more), drank, and was, by his own admission, a hellion. When, at a church youth function, the minister gathered all the boys together and asked who’d brought the flask, it was M. If anyone ever got in trouble for making a smartass remark in youth group, it was always M. He was rebellious and sometimes disrespectful, and academic concerns were of little importance in his thinking. He finished high school, but just barely.

Yet on a church youth trip to Disneyworld, he and I ended up spending an afternoon together. We’d been in separate groups during the morning, but the kids in my group had wanted to break up into small groups. “Mr. K said not to do that,” I protested. But they did it anyway, and the result was the Mr. K, the minister, followed through with his threat: they had to spend the rest of the day with him and his group of adults. I protested my innocence, and the kids in my group admitted that I’d tried to keep the group together, so I was pardoned. M and I ended up spending the rest of the day together. It was the first time we’d really spent any time together, and from that afternoon, we became close friends.

While we had little in common, what we did have in common was enough, I guess. We both loved hot food, for example, and we’d often get the spiciest salsa we could find with a bag of chips to see if we could handle it, washing it all down with Mountain Dew. We loved music, and we spent a lot of time with his grandparents playing bluegrass, Paw (as I came to call his grandfather just as he did) and I on guitar, M on banjo, and Maw singing. We both enjoyed shooting .22s at anything that would sit still long enough, and though we shot at a lot of squirrels and birds, we never hit them. Old cans and cola bottles filled with water were our favored targets. How many times can you hit that two-liter bottle before all the water drains out? The strategy is, of course, simple: start aiming at the top and work your way down. During the summer, if we needed money, we’d spend an afternoon helping this neighbor or that put up hay, and we’d earn enough for dinner, gas, and a couple of movies.

When he graduated high school the year before me, my parents asked him about his plans. “I’ll just get a job in construction, I guess.” They encouraged him to at least take a few courses at the local community college. “Then, you could start your own construction firm and you’d have the paperwork skills to run it,” my mom explained. “Nah,” he laughed, “school’s not for me.”

One July day that summer, Paw gave us a job: “There’s some raccoons that are just giving our garden hell,” he said. “I’d appreciate it if you boys’d take care of it.” We sat at the edge of a small clump of trees that summer evening, a two-liter bottle of Mountain Dew sitting between us, .22s by our sides waiting. Soon enough, three raccoons trundled into the garden. We waited until the were situated so that we could shoot away from any houses then let loose.

Maw and Paw’s farm was in a valley that seemed to echo with the sounds of neighbors’ activities, and as we fired away, we heard their nearest neighbors, who were sitting on their front porch, cheer us on: “Somebody’s gettin’ some coons!” they whooped.

Afterward, we put them in a trash bag and Maw took a commemorative picture.

Eight years after his picture, I came home for the summer after spending two years in Poland and having already committed to a third year. I went to track down M, heading to his grandparents’ farm. I didn’t know if M was still living with them or if he’d moved out. In point of fact, he’d been moved out.

“He’s locked up in the Washington County jail,” his grandmother explained. “Breaking and entering.”

I went to visit him that same afternoon. After the deputy filled out all the paperwork, I waited in the visiting room. It wasn’t a room with a row of chairs and little telephones like you see in the movies. This was no prison, just a county facility: there was a chair on the other side of the bars and the rest of the office with a single chair next to the bars on the visitors’ side. Glancing around, I saw a sign that visitors were not allowed to bring anything to inmates. I looked down at the two packs of cigarettes I’d bought him, wondering what I’d do with them, when I heard the deputy call his name: “You’ve got a visitor.” M’s face was a mixture of pleased shock and utter embarrassment. We talked for a while — I’m not sure because we never really talked about anything important. I had friends that I could sit around and talk about the existence of gods, the current political situation, the ironies of life, but with M, it was seldom more than friendly banter.

As the visit ended, I turned to the deputy. “Here’s some cigarettes. I guess you can give them to any officers who smoke since I can’t give them to my friend.” The deputy smiled: “Go ahead. It’s no big deal.”

When I returned a year later, he was incarcerated again, this time in prison; I was in Boston, starting what I thought would be a long slog to a Ph.D. in the philosophy of religion. We corresponded for about nine months, and then it just stopped just about the time I dropped out of grad school with the realization that while the philosophy of religion is an utterly fascinating topic, it has little practical value. I can’t remember who sent the last letter.

Shortly after K and I moved to America in 2005, I got word that M’s younger brother, who was in his mid-thirties like I was, had died from an aneurysm in his brain. Paw had died just a few years before that, and I hadn’t gone to the funeral because I was still living in Poland, but I was determined to go to C’s funeral.

The day before the funeral, though, a horrible storm swept through Ashville, covering the mountain I’d have to drive over with icy snow. K asked me not to take the chance; Nana begged me not to take the chance. I didn’t go.

A few years after that, Maw passed away. She’d moved in with her older daughter, and we’d moved to Greenville. For whatever reason, I didn’t go.

Some years ago, Nana got a contact number for M from his aunt, who was more like a sister — or was it the opposite, an sister so much older that she was more like an aunt? I can’t remember. I sent a text to that number, but I never got a response.

I find myself sometimes thinking about people from the past, wondering where they ended up. Social media has answered that question for so many of the people I grew up with. Others disappear. But it occurred to me that I might simply Google him.

I did, and I wish I didn’t: I find an article from the local paper where we grew up — “Bristol, Va. man arrested after agents find meth lab.” The link is to a Facebook post, so I click through, but the link to the article itself is broken. I go directly to the site and search. I find two hits.

“Please let this be a different man.”

It’s not.

A Bristol, Virginia man is charged after a tip given to police leads to the discovery of a methamphetamine lab.

Washington County, Virginia Sheriff Fred Newman said a search warrant was secured to examine a home located in the 22000 block of Benhams Road on Monday.

Deputies then arrested Michael Lee Braswell, 44, who is charged with possession with intent to manufacture 28 grams or more of methamphetamine, possess precursors to manufacture methamphetamine, allow a minor under the age of 15 to be present while manufacturing methamphetamine, and possession of meth.

Newman said Braswell is being held without bond in the Southwest Virginia Regional Jail in Abingdon. (Source 1 || Source 2)

The article is from Tuesday, September 20, 2016. I guess had I been in the area then, I could have visited him in the same jail in which I’d visited him almost twenty years earlier.

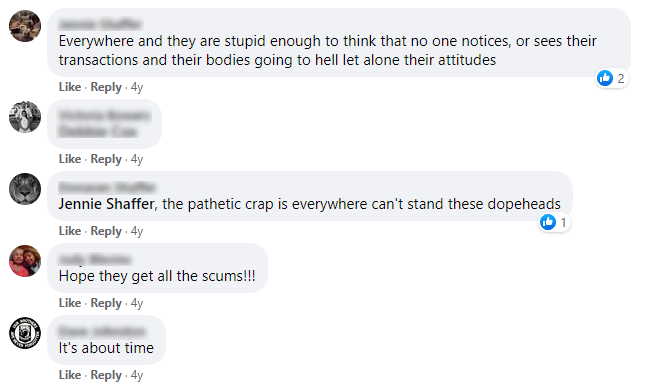

I head back to the Facebook source and read the comments:

A dear friend from my youth is being called a dopehead (I guess that’s true) and scum.

I guess I could have seen it coming when we were kids. I did see it coming. I was with him on two occasions when he bought pot. He didn’t admit. He didn’t show it to me. He certainly didn’t offer it to me, but there was no doubt. When you pull into a convenience store parking lot, and your friend gets out, goes over to another car, and sits in that car for a few minutes, coming back stuffing something in his pocket, it’s obvious. When you and your friend pull into a driveway, and a scruffy young man walks out to the car, makes small talk, then asks, “How much of that stuff did you want,” it’s obvious.

I clean up his photo in Lightroom to make him look a little less — what?

It doesn’t work. He still looks too much like a — what? A thug? An exhausted and frustrated man? I try again, trying to soften the hardness of his skin.

A little better, but there’s nothing I can do with those eyes, those forlorn eyes that seem completely lacking in surprise, completely resigned to his reality, completely fatalistic.

Every year, there’s a kid or two on the hall that I find myself wondering about, thinking that he or she might end up like this. There’s the same resignation about them, the same air of fatalism. Every year I try to help them, to show them that they do have some control over their fate, to show them that more is in their hands than they probably realize (though the cards are often stacked against them). To try to prevent them from being a photo someone looks at thirty years later, wonders whatever happens to them, then loads a search engine and beings looking…

0 Comments