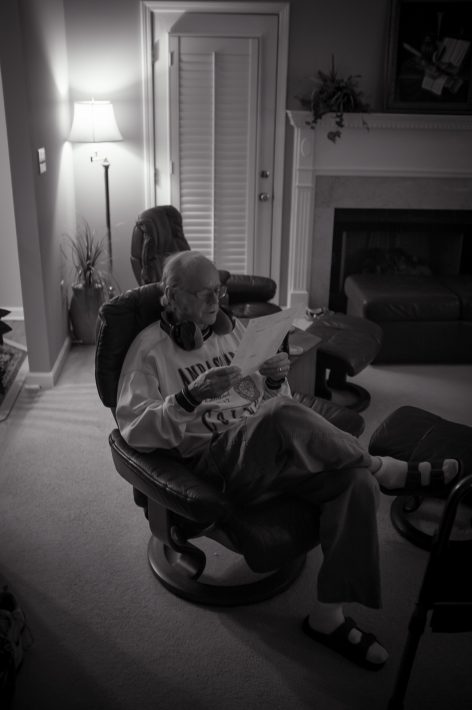

With Nana still in rehab and Papa alone, we take care of them the best we can. Poor Nana has to put up with institutional food, which, she claims, is not terrible, but which I also know is not great. Poor Papa can cook eggs and warm things up in the microwave, but he’s never done much more than that.

This afternoon, since it was MLK Day and the kids and I had the day off, we took over a favorite chicken sandwich for Nana and cheered as we saw evidence of an ever-increasing appetite.

In the evening, we went to make dinner at Papa’s. We either cook something here and take it over every night or take everything there to cook.

Other than that, an uneventful day. I spent an hour in the morning planning lessons for the next several days (this week and a little beyond) for one class and another hour in the afternoon planning for another class, plus half an hour in the evening grading papers.

This year, I’ve kept track of all my out-of-classroom hours — planning, grading, going to meetings, etc. For this first semester, I’ve spent 115 hours above the 40-hour work weeks. That’s just a little over half a day shy of three full work weeks. If I keep this pace up — and I see no reason why I wouldn’t — I’ll have spent close to six weeks’ worth of time outside the classroom doing work. Add to that the half-hour morning duty I have every third week, which makes 2.5 hours a week or 30 hours for the year, and I’ll have 260 hours of additional work on top of my normal work week. That’s six and a half weeks of work. I have about nine weeks off during summer break, but I probably spend an additional 40 or so hours over the summer planning for the coming year. (I’ll keep track this summer.) That’s seven and a half weeks of work, which means my summer “vacation” is really not much of vacation — I’ve just put in the hours in advance.

I don’t say this to complain. Much of the time I spend grading is because I try to push my kids as hard as I can, which produces a lot of material for me to assess. I have a reputation to keep up, after all: students tell me that they’ve heard since they entered the school in sixth grade that I’m the most demanding teacher in the school. I don’t know about that, but it certainly doesn’t hurt one’s sense of self-worth to hear something like that. In other words, I could do less work and get by, but then it wouldn’t be the Dread Teacher Mr. Scott’s.

Finally, I must have been under a rock, but I just learned of Mary Oliver’s death tonight, listening to the news in the car. A poet of fairly simple verse, she’s always a great choice for thirteen-year-olds. In past years, when I had students put together annotated portfolios as their culminating poetry unit project (which is not to say I have my students read poems for one dedicated unit and then neglect poetry for the rest of the year, but I find it’s good to spend three or four weeks focusing on what makes poetry poetry to equip them for the rest of the year), almost every student included an Oliver poem, and they all said they liked her because she’s easy to understand. I personally have always liked poems that require a bit more digging, but that’s not to say I’m a big fan of someone like Louis Gluck, someone who writes poetry that is almost impenetrable. My favorites — Bishop, Heany, Levine, and the like — require some thought, require a bit of effort, but always reward with a moment of stunned epiphany.

And since I’ve been talking about work, why not include Levine’s poem on the same subject:

I must interject! “My favorites require some thought…” And Mary Oliver doesn’t? Then you’re missing her message. I’ll say no more. But here’s an article that pretty much shares my view of her work. It was written before her death.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/11/27/what-mary-olivers-critics-dont-understand

I like a poem that’s a little like a puzzle. Not much. Just a bit. Sort of like a good life. That’s all I meant. :)

I think you’re just way ahead of the rest of us in being able to decipher a poem. But, to stick to my guns — thre’s meaning and there’s meaning. Your 13 year olds also love and understand Romeo and Juliet. It speaks to them! But it isn’t until you’ve taught them to read those incredible lines that they come to really understand R&J! Oliver’s poems are easy at the outset. But there is much more meaning than at first glance. Not unlike Szymborska. Do you like Szymborska?

I like Szymborska because I can read her in Polish and largely understand her work. I have a bilingual edition of some of her poetry, and I like reading the Polish, thinking how I might translate it, then looking at how Clare Cavanagh translated it. Sometimes, so much difference — an entirely different poem in English.