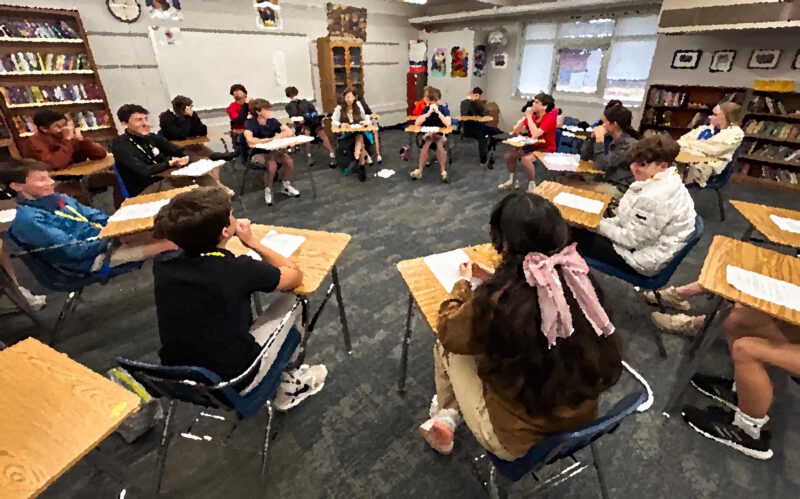

The setup is simple: two circles of desks created of triads of one inner-circle desk and two outer-circle desks. Students in the inner circle can talk; students in the outer circle can only listen until they tag in and exchange places with an inner-circle student. However, the desks are usually set up in rows, so students have to rearrange the desks to get them in these circles.

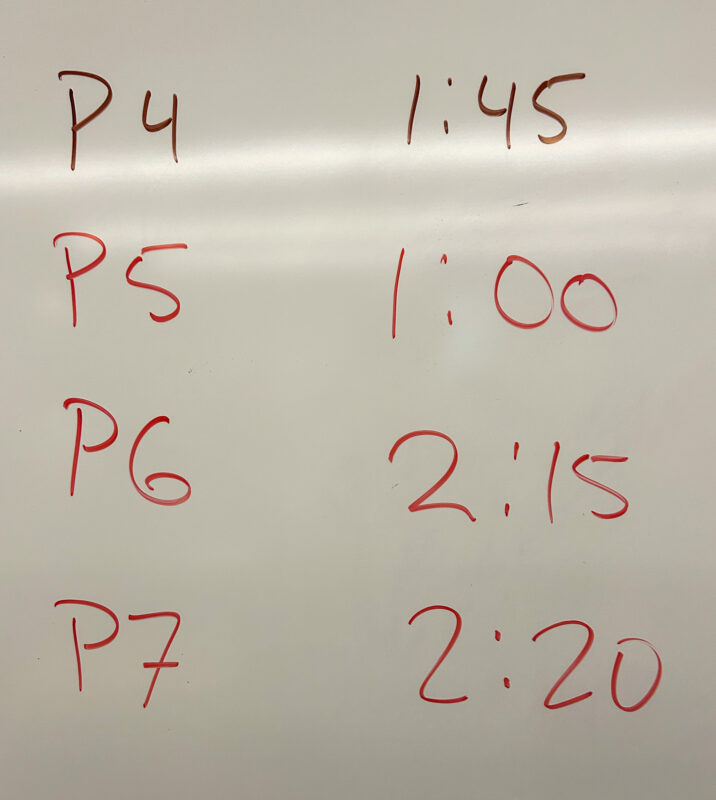

I often race classes to see who can settle the rearrangement the fastest. The results are telling:

My P4 and P5 classes are my honors classes; my P6 and P7 classes are my on-level groups. The result is consistent: the honors classes get the job done faster than the on-level classes.

Why is this?

The on-level classes sometimes refer to the honors classes as “the smart-kids classes,” and I often point out that they’re not smarter. They usually just work harder. They stay focused in class and give their best effort at all times. When I ask them to do something at home, they generally do it. The thing is, they’ve been doing this for years, so they’ve gradually become increasingly better students — better readers, better writers.

I know that for many of the honors kids, there is a socioeconomic element at play as well. They most likely live in homes with more books. Their fathers and mothers are lawyers and teachers, so they see reading and writing modeled frequently. And most of them come from two-parent family, which offers great economic advantages over single-parent households. This is not to say all these factors are true for all honors students or that none of these factors are true for on-level students. There are a lot of factors at play.

Be all that as it may, though, the honors kids get the desks arranged faster. This is connected to executive functioning more than academic achievement. So which came first? Probably neither: both were nurtured at every turn by a number of different adults, and the numbers tell that story.