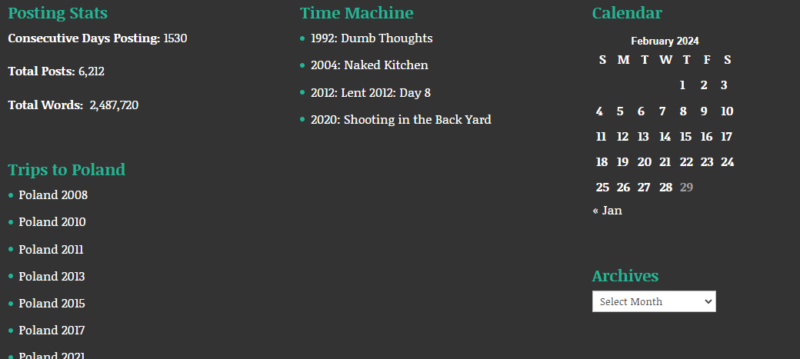

I was very surprised for a moment when checking the Time Machine widget at the bottom of the site: only four entries for this day?! And then I remembered the date.

And realized one of the entries had to do with the kitchen remodel Babcia and Dziadek decided to do when K and I got engaged. They’d planned to do something else with the money, but in the end, they went for the remodel. “If we’re going to have guests from the States…” I seem to recall Dziadek explaining.

Looking at that picture, I think how much younger Babcia looked. It was twenty years ago, and it hits me: in this picture, she’s only a handful of years older than I am now. And the last two decades have simply floated by without any effort and little notice.

And the next two decades?