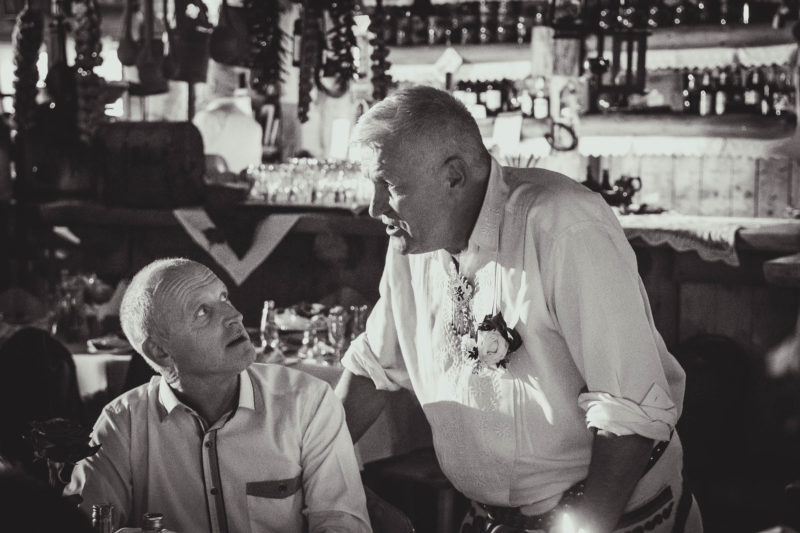

Here in Jablonka, we began our last day with rain and temperature keeping us indoors. It never rose above the high-50s, and it rained all morning before taking a short lunch break to prepare for an afternoon and evening of rain. Depressing weather to go with a day of mixed feelings: ready to go home, we’re both a little sad to leave the adventure here.

In the meantime, K flew out of our local airport heading to Newark for a funeral. In New York, it was sunny and lovely, and K got to see a friend she hadn’t seen for years. Still, the motivation for the trip was a tragedy. A mixture as here.

With the weather as it was, we had few choices this last day in Jablonka. We watched some television, talked, packed — and repeated it all.

And for dinner: kiszka heated on the stove Babcia uses for hot water.

Random Bit for Future Smiles

A regular during our stay here was was the Magno-Z commercial: we got to see that a few times during our month here. The Boy groaned each time it came on, but he still sang along with it.

Commercials, it turns out, are a great source for learning a language.