The last question for the act three study guide was to complete a paraphrase of lines 94-103. It was one of the few questions I actually check — the rest of them, I skim and make sure they put something close to correct. This one I read.

One young lady (we’ll call her Lisa) turned in the following:

I’m so upset about my cousin’s death that I’ll never be satisfied with Romeo until I see him dead. Mother, if you could find a man who sells poison, I would mix it myself so that Romeo would be dead. My heart hates hearing his name and not being able to go after him, not being able to avenge the love I had for my cousin.

The second part wasn’t as simple: explain the paradoxical/ironic phrases in this passage.

This passage is ironic because Juliet has to pretend that she hates Romeo and wants to kill him even though in reality she loves him and wants to protect him. Juliet says that she will never be satisfied until she sees Romeo dead when in reality she won’t be satisfied until she sees Romeo and can hug him and be with him. Juliet tells her mother that she wants to mix up the poison to kill Romeo but she really wants to mix up the poison so she can protect Romeo and make sure that the poison doesn’t kill him. Also, Juliet hates to hear Romeo’s name and not go after him, but she says that she hates hearing Romeo’s names and not being able to avenge Tybalt’s death to cover-up that fact that she loves Romeo.

My comment: “Good work. A thorough examination of all the levels of irony.” Lisa is, in all respects, a star student. She never gives less than 115%, and she absolutely hounds me to death for extra feedback and additional help. As a result, she finished the second quarter this year with an eye-popping grade of 100. She had a 99 without the extra credit for the quarter, but she did every possible bit of extra credit so I was more than happy to give that one point, though she didn’t have to do everything to get that point. But she would have done it all even if I’d told her she didn’t have to. “I just want to make sure,” she’d likely say.

A couple of students later, I was skimming through the answers, thinking how much more complete these answers seem than what I’m used to receiving from the boy (we’ll call him James). Then I get to the paradox question and read his answer:

This passage is ironic because Juliet has to pretend that she hates Romeo and wants to kill him even though in reality she loves him and wants to protect him. Juliet says that she will never be satisfied until she sees Romeo dead when in reality she won’t be satisfied until she sees Romeo and can hug him and be with him. Juliet tells her mother that she wants to mix up the poison to kill Romeo but she really wants to mix up the poison so she can protect Romeo and make sure that the poison doesn’t kill him. Also, Juliet hates to hear Romeo’s name and not go after him, but she says that she hates hearing Romeo’s names and not being able to avenge Tybalt’s death to cover-up that fact that she loves Romeo.

A few more students later, I read another boy’s work. We’ll call him Nate. Nate has been struggling with the class, but he’s constantly saying he wants to do better. I read his paradox answer:

This passage is ironic because Juliet has to pretend that she hates Romeo and wants to kill him even though in reality she loves him and wants to protect him. Juliet says that she will never be satisfied until she sees Romeo dead when in reality she won’t be satisfied until she sees Romeo and can hug him and be with him. Juliet tells her mother that she wants to mix up the poison to kill Romeo but she really wants to mix up the poison so she can protect Romeo and make sure that the poison doesn’t kill him. Also, Juliet hates to hear Romeo’s name and not go after him, but she says that she hates hearing Romeo’s names and not being able to avenge Tybalt’s death to cover-up that fact that she loves Romeo.

At this point, there was only one thing to do: go back through all the other papers and check. Nothing else seemed suspect, but these Lisa’s, James’s, and Nate’s study guides were, upon closer inspection, identical. Completely. Perfectly. A medieval scribe would be jealous of the letter accuracy.

I was puzzled, though. I couldn’t get a single thought out of my mind: “This just does not seem like something Lisa would do.” James and Nate — maybe. Conceivably. But Lisa? Never.

I took the three papers to Mrs. D, the eighth-grade vice principal, and she sweated a couple of more names out of them. I got a call during my planning period asking if I’d print out Sam’s and Jacob’s paper. I did so, but they were identical to the other three. Mrs. D applied a little more pressure while I stood there: “You want to tell me what happened or should I immediately just start suspending people?” It turned out that both James and Nate had gotten the study guide from Jacob.

While they were providing details, I looked down at Lisa. Her brow was furrowed in confusion; her eyes glistened; her chest was heaving slightly. She was utterly terrified.

It wasn’t difficult to understand why: here was a girl who’d probably never gotten in trouble at school. Ever. For anything. She’s chatty because she’s so very bright, and she just wants to share all the thoughts she has. (She puts Post-It notes on her article of the week in addition to all the marginal comments. “I just have a lot to say,” she explained with shrug of the shoulders when I asked her why she was doing so much more than was required.)

I left the room to get ready for class — their class. Students began filing in, and I heard the talk:

“Who else got called to the office?”

“Lisa’s in there.”

“Then it must be some star student thing or something.”

“No, I think she’s in trouble.”

Just before class started, the vice principal came down to my room to tell me that Jacob had rather casually admitted that he’d swiped the study guide from Lisa. While she had gone to the restroom, he noticed the study guide was up and quickly jumped on her computer to send a copy to himself. He then shared it.

Poor Lisa, I thought.

I went back into the classroom and made sure everyone was working, then called Lisa outside.

“Are you okay?” I asked.

“Yes. Did Mrs. D tell you what happened?”

“Yes, and I’m glad it all came out. I’m sure you were quite confused.”

“Very,” she said, shaking her head vigorously.

“Well, this should serve as a lesson to you that’s a little different than the lesson the boys are going to learn.” I asked her if Mrs. D had told her what I’d said initially.

“No, not really.”

“Well, I told her that it just didn’t seem like you. That I doubted you’d just shared this. I didn’t have any way to explain it, but I really didn’t think you would do something like this.” She smiled, and I continued, “So the lesson I hope you learn in a very real way is how valuable the reputation you’ve created for yourself is, how important it is to maintain such a reputation because it will serve you well in ways you probably didn’t previously imagine.”

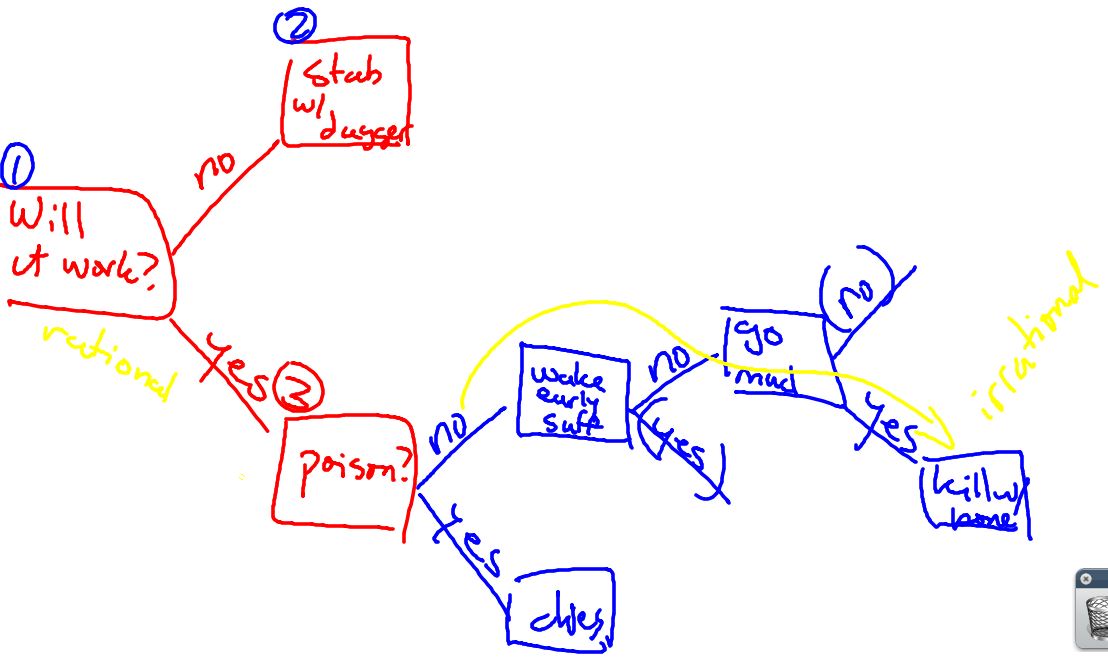

She smiled again, and we went back inside and had a great class, making a decision tree of Juliet’s concerns about taking Friar Lawrence’s potion.

Farewell! God knows when we shall meet again.

I have a faint cold fear thrills through my veins,

That almost freezes up the heat of life:

I’ll call them back again to comfort me:

Nurse! What should she do here?

My dismal scene I needs must act alone.

Come, vial.

What if this mixture do not work at all?

Shall I be married then to-morrow morning?

No, no: this shall forbid it: lie thou there.Laying down her dagger

What if it be a poison, which the friar

Subtly hath minister’d to have me dead,

Lest in this marriage he should be dishonour’d,

Because he married me before to Romeo?

I fear it is: and yet, methinks, it should not,

For he hath still been tried a holy man.

How if, when I am laid into the tomb,

I wake before the time that Romeo

Come to redeem me? there’s a fearful point!

Shall I not, then, be stifled in the vault,

To whose foul mouth no healthsome air breathes in,

And there die strangled ere my Romeo comes?

Or, if I live, is it not very like,

The horrible conceit of death and night,

Together with the terror of the place,–

As in a vault, an ancient receptacle,

Where, for these many hundred years, the bones

Of all my buried ancestors are packed:

Where bloody Tybalt, yet but green in earth,

Lies festering in his shroud; where, as they say,

At some hours in the night spirits resort;–

Alack, alack, is it not like that I,

So early waking, what with loathsome smells,

And shrieks like mandrakes’ torn out of the earth,

That living mortals, hearing them, run mad:–

O, if I wake, shall I not be distraught,

Environed with all these hideous fears?

And madly play with my forefather’s joints?

And pluck the mangled Tybalt from his shroud?

And, in this rage, with some great kinsman’s bone,

As with a club, dash out my desperate brains?

O, look! methinks I see my cousin’s ghost

Seeking out Romeo, that did spit his body

Upon a rapier’s point: stay, Tybalt, stay!

Romeo, I come! this do I drink to thee.

I’ve always loved this lesson: the decision tree helps them literally see how increasingly irrational Juliet is becoming:

Lisa was classic Lisa: she took control of her group; she offered her ideas enthusiastically but humbly; she listened to others and helped everyone synthesize their thoughts. Back to normal. Classic Lisa. The Lisa everyone was thinking of, scratching their heads, wondering, “Lisa, in trouble?”

And the boys? Well, I didn’t talk to them. After all, what could I say that Mrs. D hadn’t already said?

0 Comments