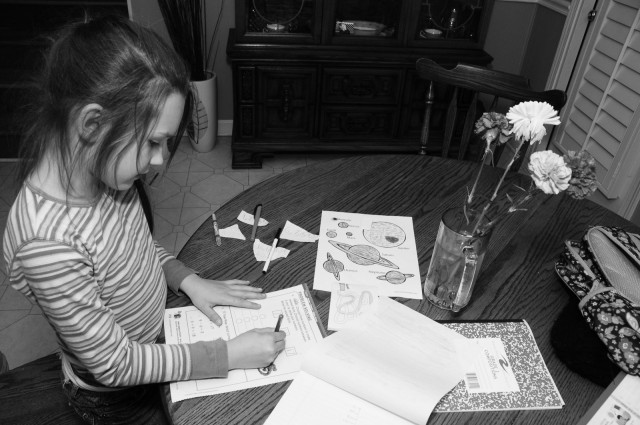

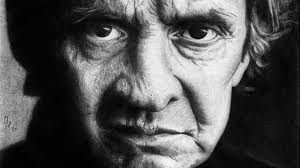

About the only time I was indoors all day was for this shot, taken as I was finishing up my coffee and heading out to

- finish the backyard leaf clean up, including

- the mulching of multiple wheelbarrow-loads of leaves;

- the hauling of countless loads of branches and twigs to the roadside; and,

- the removal sand from the backyard deposited by last spring’s flood;

- prepare the raspberry patch including

- the removing of leaves and debris; and

- the depositing of a twelve-inch layer of mulched leaves (see above) on the raspberry patch;

- clean the front flower bed, including

- the removing of numerous leaves; and,

- the cutting back of last year’s jasmine;

- apply various concoctions to the yard including

- the applying fertilizer to isolated patches of the yard I missed two weeks ago; and,

- the applying preemergent weed killer to the rest of the lawn;

- sow grass seed in the entire backyard;

- remove countless Sweet Gum seed balls from the front yard;

- spray insecticide around the outer edges of the house;

- and finally, fall into a heap to watch Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil with my equally exhausted K, who

- cleaned the house;

- cared for the kids;

- went shopping;

- planted strawberries; and

- prepared supper.

In short, a perfect spring Saturday.