walkin’ down the street…

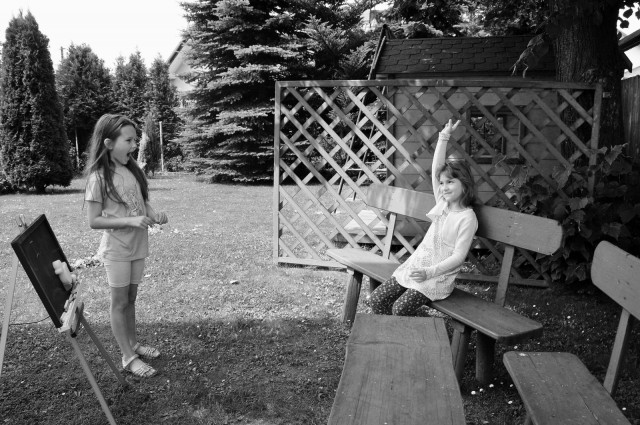

Such a difference in how L plays here in the States versus Babcia’s place in Polska. With all the houses tightly packed in Babcia’s neighborhood, I could easily hear L just about anywhere she was. She’d developed a few little haunts, but they were all within earshot of the house. Here, I watch her as she walks up the street to her friend’s house, and his parents do the same when they return. It’s a busier street to begin with, but there’s also the eternal fear that sparks the almost cliche instructions, “Don’t talk to strangers.” In Polska, there were times that I didn’t really know where L was, but I wasn’t really worried about it. It’s not that there aren’t evil people in Polska, they just seem fewer and farther between. You don’t read news accounts of abductions and murders like you do here.

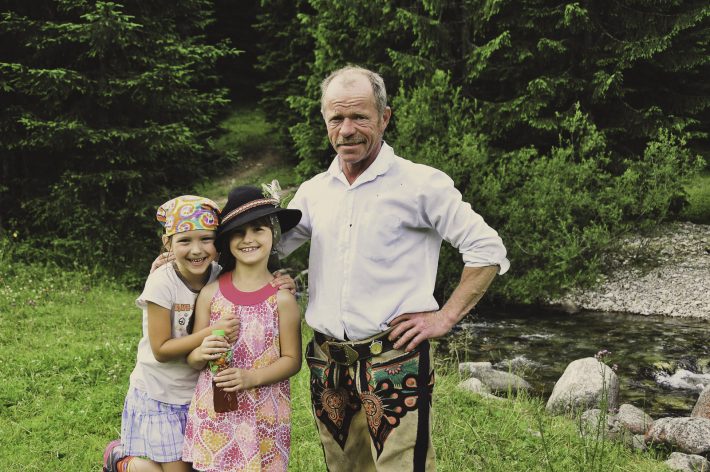

And so L and S would often strike out on their own, yelling to one of us on their way out where they were headed.