There are movies out there that are so awful that you just have to recommend them to your friends. Like the old Saturday Night Live sketch in which Chris Farley has everyone trying the rancid milk and rubbing his clammy belly, there are some evils that we simply must share to appreciate.

The Omega Code is one of them. Without a doubt, it is the worst movie I’ve ever seen, yet one film everyone should endure just to see how bad a movie can be.

There is nothing redeeming about this film, and that’s its perverse charm. The acting is awful, sometimes too hot, sometimes too cold, most times just not there; the script is pathetic, ranging from faux Elizabethan nonsense to middle school scribblings; the special effects are neither special nor effective; the cinematography is along the lines of “put the camcorder there and hit the red button”; the soundtrack has all the subtlety of a mix prepared by an eight grader who’s just discovered Carl Orff; the direction lacks any whatsoever; the costumes are late-eighties high school drama club quality.

If someone sat down to plan a worse movie, it would be tough to top this one.

A look at the production credits brings everything into focus, though. TBN Films, as in “Trinity Broadcast Network”–Paul Crouch’s network. Writing credits include Hal Lindsey as a consultant for biblical prophecy.

A-ha! It’s not the film itself that’s important, but the ideology behind it. In short, it’s propaganda portraying the soon-coming end of the world according to a certain fundamentalist Christian interpretation of the Bible.

As a bizarre aside, there is a bizarre theological menage a trios involved in this film that is about as dumbfounding as the film itself. Both Casper Van Dien and Michael Ironside play in The Omega Code and Starship Troopers. Troopers, in turn, was directed by Paul Verhoeven, who was a fellow of the notorious Jesus Seminar, the ultimate liberal theologians club, hated and scorned by Crouch’s TBN. Talk about working with directors of diverging views!

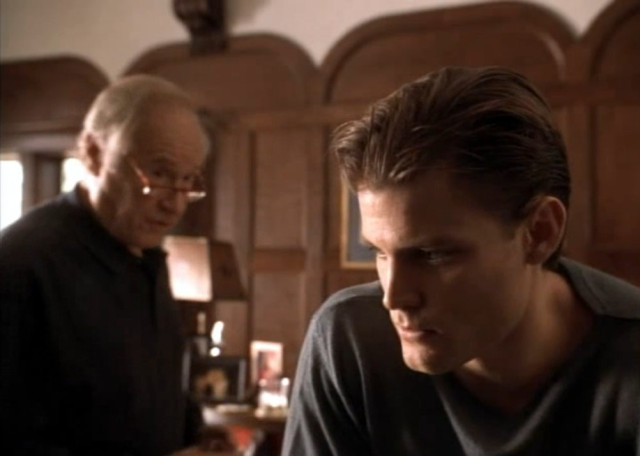

Michael York plays Stone Alexander, “beloved media mogul turned political dynamo,” whose rise to power is never explained. Within a few minutes of the film, however, he’s “named chairman of the European Union,” developed “an inexpensive, high-nutrient wafer that can sustain an active person for more than a day and a revolutionary form of ocean desalination that will bring life-giving water to the driest of deserts,” and won the “United Nations Humanitarian award.”

And there you have it, folks: if you haven’t figured it out already, Alexander is going to set himself up as the miracle-working Beast prophesied in the Book of Revelation.

Initially, “motivational guru Gillen Lane,” played (or rather, played at) by Casper Van Dien, joins forces with Alexander in an effort to make a cliche difference in the world. He soon realizes the evil of Alexander’s true aims and becomes determined to stop him.

In the meantime, though, he has some of the choicest moments of the film, often serving up the lines that other characters hang themselves with. For example, Lane suggests that, in order to motivate people, Alexander needs to be someone “to rally behind,” an “archetypal figure to embody the message.” His ultimate suggestion, after mention Martin Luther King and Gandhi, is “a new Caesar,” to which Alexander memorably replies,

Oh, no, no! No, not Caesar! Why man, he’d have to stride the narrow world like a colossus, and we petty men walk beneath his huge legs and peep about to find ourselves dishonorable graves. Oh, no! No, I’m not that ambitious.

Yes, your sophomore English serves you well–Julius Caesar, Act I, Scene ii.

Is this an attempt at high-brow script writing, or is it York improvising, flexing his theatrical muscle, so to speak? I’m not sure which alternative is more frightening.

Yet as the film progresses through the second half, it gets worse. Or better. Or both, if you’re a masochist.

Some examples: Alexander develops technology that “neutralizes” nuclear weapons, unites the world into a single government, with a single-currency, rebuilds Solomon’s Temple, and literally comes back from the dead.

Gillen Lane’s close friend Sen. Jack Thompson, played by George Coe (The Mighty Ducks, Bustin’ Loose), laments,

I don’t know anything about visions. I never had one. But I know about marriage. And I know about family. And I know the worth of a real man will show in the countenance of his wife’s face.

The director, Robert Marcarelli, introduces bizarre attempts at plot twisting which, to anyone really thinking during the film, are inexplicable plot complications. Characters faced with immanent danger react with increasingly baffling shortsightedness. And most puzzling, the relationship between the purported Bible code (the crisscross, three-dimensional code supposedly hidden in the Torah, a la Jewish Kabbalah) and Biblical prophecy is never explained, though it seems clear to everyone in the film.

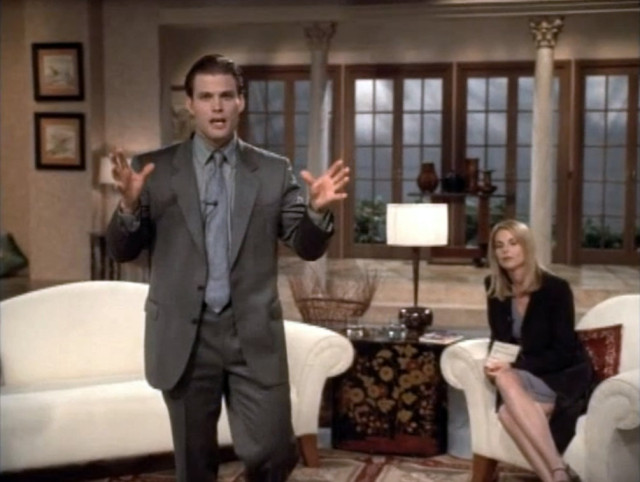

This is perhaps the film’s most confusing point. The waters get muddied right at the film’s opening, when Lane, who also has “a doctorate in both world religion and mythology from Cambridge,” is interviewed on a talk show by Cassandra Barashe, played by Catherine Oxenberg.

Barashe: In addition to your many other accomplishments, you seem to be an expert on the Bible code. […] Explain to our audience what this Bible code is, and how it works.

Lane: Well, crisscrossing the Torah is a code of hidden words and phrases that not only reveals our past and present, but foretells our future. […] Most amazingly, in the Book of Daniel, an angel tells him to seal up the book until the end of days. But Rostenburg[, an expert on the Bible code,] may have found the key to unlock it. See, he believed that the Bible was actually a holographic computer program and that instead of two dimensions, it should be studied in three. If this could be achieved, the code would actually feed us prophecies of our coming future. Anyway, the reason I discuss this in my book is because what we want to believe as religion really traces back to myths born out of our collective consciousness.

Barashe: Has anyone raised the question of how people like yourself can believe in these hidden codes within the Bible, and yet not in the Bible itself?

Lane: You mean like, “Jesus loves me, this I know [Looks at the audience with skeptically raised eyebrows], for the Bible [Air quotes, returning his gaze to Barashe] tells me so?” [Looks at the audience as they laugh at his wittiness]

Barashe: Yes, exactly.

Lane: My mother used to sing me that song. But you know what? She died in a tragic car accident when I was ten years old, and I finally realized that her faith in this loving God, her truth, was just a myth. Therefore, myth must be truth.

This kind of twisted logic is the basis for the film and snakes its way throughout the whole script. The Beast rises to power by following the secret codes of the Bible, yet we’ve all been warned of it in the books of Daniel, Ezekiel, and Revelation, as other characters make clear. We’re left wondering, “If it was supposed to be so clear to us mere mortals, why did Satan–and that’s really who Michael York’s Stone Alexander is, a possessed megalomaniac–need the secret Bible code to figure out how to bring it all to fruition?”

That’s a question that not only does the film not answer, but it doesn’t even realize it raises it. I suspect this confusion between code and prophecy arises from TBN’s effort to get “real prophecy” into a mass marketed, main-steam film. The popularity of Michael Dorsnin’s The Bible Code and similar books seems to have gotten the writers at TBN to thinking, “Hey, we can use this as a springboard into the Bible’s real code: prophecy!” As a result, it’s a mess.

As a whole, the biggest flaw of The Omega Code is its earnestness. Films usually don’t take themselves as seriously as The Omega Code does, for it not only depicts but is a battle against the wiles of the devil. Yet what the cast and crew end up making, instead of the Biblically-based, thought-provoking thriller they think they’re working on, is a B-movie, and the absolute worst kind: an accidental B-movie. It’s “B” status slipped up unawares, probably just a few moments behind the initial idea was taken seriously by all involved.

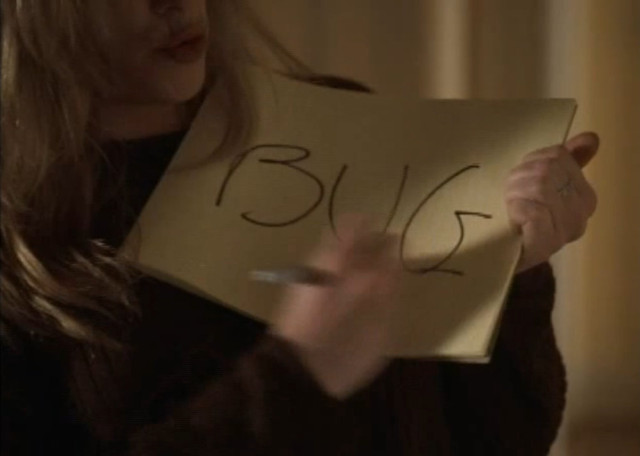

Even if the film were made in earnest but intelligently, it wouldn’t be so bad. But not only are we dealing with an awfully written script, but we’re also enduring characters who are simply stupid. They scribble “bug” on a legal pad to let one another know a room’s wired, then proceed to talk in hushed stage whispers that no known listening device can detect. They run for their lives, literally the most wanted individual on the planet, then start ranting about visions they’re having when they finally find someone who’ll help them.

God bless them all, but they’re freaking idiots, each and every one!

The clear stupidity of the characters lets us sigh in relief, though. In the end, their idiocy transforms the film into a hopeful vision for the future, because if Revelation’s Beast turns out to be half as dimwitted as any one of the characters in this film, there’s hope for humanity.

Unless he starts producing films.