This content has restricted access, please type the password below and get access.

Month: January 2006

I znowu brakuje mi czasu.

Zaniedbuje bloga, wiem ale bezgranicznie oddalam sie urzadzaniu naszego mieszkania.

Szyje zaslony, poduszki, w grudniu malowalismy ragaly a prucz tego zwyczajny rytm — praca, dom I nasze coraz ciekawsze zycie towarzyskie. Czas tak strasznie szybko mi biegnie I ciagle mi go na cos brakuje. A wszystko rozpedzilo sie listopadzie, kiedy lokalna galeria przyznala nam miejsce na scianie I postanowilismy sprobowac sprzedawac nasze zdjecia. Przygotowanie wystawy zajelo nam pol listopada I pierwszy tydzien grudnia. Wszystkie wieczory I weekendy spedzalismy tnac paspartu, oprawiajac zdjecia I przygotowujac skromna dekoracje naszej sciany — Koliba. Koliba ruszyla pierwszego grudnia I niestety nie prosperuje zbyt dobrze, do tej pory sprzedalismy tylk jedno zdjecie. Wiec jak na razie zainwestowalimsy w Kolibe troche pieniedzy i mnostwo czasu a w zamian pozostaje nam jedynie satysfakcja, ze nasze zdjecia wisza w jednej z bardziej znanych galerii w centrum miasta. Pozniej ruszylismy ostro z przygotowaniami swiatecznymi. Ja jak to moja mama mowi umiem sobie narobic roboty. Wymyslilismy sobie regal na ksiazki I dwa male regaly na plyty kompaktowe. A ze nasze potrzeby ciagle sa wieksze niz dostepne fundusze kupilismy meble z surowego drewna I sami postanowilismy je pomalowac. Gary niestety bardzo szybko odpadl z calej imprezy bo po kazdym malowaniu dostawal strasznych bolow glowy. Zostalam wiec sama z trzema regalami, ktore malowalam w lazience, bo niestety bylo juz za zimno zeby malowac na balkonie. W lazience miescil sie tylko jeden, wiec malowalam je kolejno, warstwa po warstwie (2 do czterech warstw koloru i po trzy warstwy lakieru bezbarwnego), dzien po dniu, bo farba musiala schnac przynajmniej 4 godziny. Wracalismy wiec z pracy, Gary zabieral sie za gotowanie a ja za malowanie i tak w kolko przez trzy tygodnie a w miedzyczasie przygotowalismy swieta z gruntownym sprzataniem, pieczeniem i gotowaniem — dokladnie tak jak w domu. Teraz zabralam sie za okna. Szukalam karniszy, wieszlam polskie firanki, ktore mama przyslala nam na gwiazdke. Szyje zaslony i poszewki na poduszki pod kolor — generalnie znowu narobilam sobie roboty.

Faktycznie to wszystko pochlania mi mnustwo czasu i wieczorami przewaznie padam zmeczona do lozka. Ale warto, po pierwsze swieta byly bardzo udane, i my, i nasi goscie milo spedzilismy czas, po drugie to wszystko bardzo mnie cieszy i pochlania, planuje, kombinuje, szukam okazji po miescie no i przede wszystkim nasze mieszkanko wyglada coraz przytulniej. Obydwje stwierdzilimy, ze powoli zaczynamy myslec o tym mieszkaniu jak o naszym domu. No a dzisiaj przychodzi do nas Kuba z rodzina. Kube poznalam w lokalnym rosyjskim sklepie, jest Polakiem, mieszka w Asheville juz kilka lat. Dzisiaj przychodzi ze swoja rodzina na kolacje. Jestesmy bardzo ciekawi i zony, ktora jest Blugarka i dzieciakow, ktore wychowuja sie w trzyjezycznej rodzinie.

The Omega Code

There are movies out there that are so awful that you just have to recommend them to your friends. Like the old Saturday Night Live sketch in which Chris Farley has everyone trying the rancid milk and rubbing his clammy belly, there are some evils that we simply must share to appreciate.

The Omega Code is one of them. Without a doubt, it is the worst movie I’ve ever seen, yet one film everyone should endure just to see how bad a movie can be.

There is nothing redeeming about this film, and that’s its perverse charm. The acting is awful, sometimes too hot, sometimes too cold, most times just not there; the script is pathetic, ranging from faux Elizabethan nonsense to middle school scribblings; the special effects are neither special nor effective; the cinematography is along the lines of “put the camcorder there and hit the red button”; the soundtrack has all the subtlety of a mix prepared by an eight grader who’s just discovered Carl Orff; the direction lacks any whatsoever; the costumes are late-eighties high school drama club quality.

If someone sat down to plan a worse movie, it would be tough to top this one.

A look at the production credits brings everything into focus, though. TBN Films, as in “Trinity Broadcast Network”–Paul Crouch’s network. Writing credits include Hal Lindsey as a consultant for biblical prophecy.

A-ha! It’s not the film itself that’s important, but the ideology behind it. In short, it’s propaganda portraying the soon-coming end of the world according to a certain fundamentalist Christian interpretation of the Bible.

As a bizarre aside, there is a bizarre theological menage a trios involved in this film that is about as dumbfounding as the film itself. Both Casper Van Dien and Michael Ironside play in The Omega Code and Starship Troopers. Troopers, in turn, was directed by Paul Verhoeven, who was a fellow of the notorious Jesus Seminar, the ultimate liberal theologians club, hated and scorned by Crouch’s TBN. Talk about working with directors of diverging views!

Michael York plays Stone Alexander, “beloved media mogul turned political dynamo,” whose rise to power is never explained. Within a few minutes of the film, however, he’s “named chairman of the European Union,” developed “an inexpensive, high-nutrient wafer that can sustain an active person for more than a day and a revolutionary form of ocean desalination that will bring life-giving water to the driest of deserts,” and won the “United Nations Humanitarian award.”

And there you have it, folks: if you haven’t figured it out already, Alexander is going to set himself up as the miracle-working Beast prophesied in the Book of Revelation.

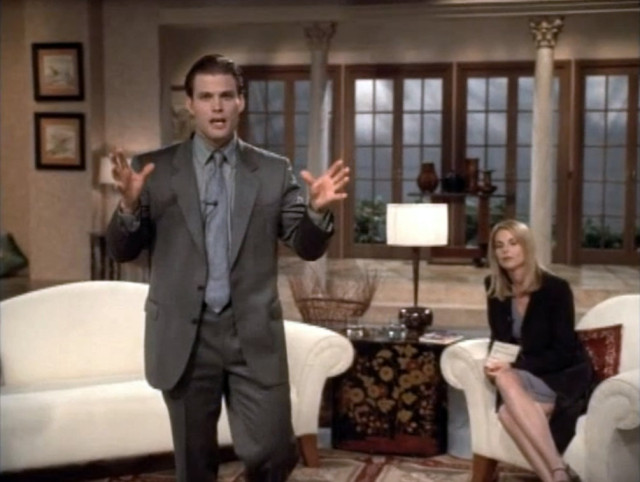

Initially, “motivational guru Gillen Lane,” played (or rather, played at) by Casper Van Dien, joins forces with Alexander in an effort to make a cliche difference in the world. He soon realizes the evil of Alexander’s true aims and becomes determined to stop him.

In the meantime, though, he has some of the choicest moments of the film, often serving up the lines that other characters hang themselves with. For example, Lane suggests that, in order to motivate people, Alexander needs to be someone “to rally behind,” an “archetypal figure to embody the message.” His ultimate suggestion, after mention Martin Luther King and Gandhi, is “a new Caesar,” to which Alexander memorably replies,

Oh, no, no! No, not Caesar! Why man, he’d have to stride the narrow world like a colossus, and we petty men walk beneath his huge legs and peep about to find ourselves dishonorable graves. Oh, no! No, I’m not that ambitious.

Yes, your sophomore English serves you well–Julius Caesar, Act I, Scene ii.

Is this an attempt at high-brow script writing, or is it York improvising, flexing his theatrical muscle, so to speak? I’m not sure which alternative is more frightening.

Yet as the film progresses through the second half, it gets worse. Or better. Or both, if you’re a masochist.

Some examples: Alexander develops technology that “neutralizes” nuclear weapons, unites the world into a single government, with a single-currency, rebuilds Solomon’s Temple, and literally comes back from the dead.

Gillen Lane’s close friend Sen. Jack Thompson, played by George Coe (The Mighty Ducks, Bustin’ Loose), laments,

I don’t know anything about visions. I never had one. But I know about marriage. And I know about family. And I know the worth of a real man will show in the countenance of his wife’s face.

The director, Robert Marcarelli, introduces bizarre attempts at plot twisting which, to anyone really thinking during the film, are inexplicable plot complications. Characters faced with immanent danger react with increasingly baffling shortsightedness. And most puzzling, the relationship between the purported Bible code (the crisscross, three-dimensional code supposedly hidden in the Torah, a la Jewish Kabbalah) and Biblical prophecy is never explained, though it seems clear to everyone in the film.

This is perhaps the film’s most confusing point. The waters get muddied right at the film’s opening, when Lane, who also has “a doctorate in both world religion and mythology from Cambridge,” is interviewed on a talk show by Cassandra Barashe, played by Catherine Oxenberg.

Barashe: In addition to your many other accomplishments, you seem to be an expert on the Bible code. […] Explain to our audience what this Bible code is, and how it works.

Lane: Well, crisscrossing the Torah is a code of hidden words and phrases that not only reveals our past and present, but foretells our future. […] Most amazingly, in the Book of Daniel, an angel tells him to seal up the book until the end of days. But Rostenburg[, an expert on the Bible code,] may have found the key to unlock it. See, he believed that the Bible was actually a holographic computer program and that instead of two dimensions, it should be studied in three. If this could be achieved, the code would actually feed us prophecies of our coming future. Anyway, the reason I discuss this in my book is because what we want to believe as religion really traces back to myths born out of our collective consciousness.

Barashe: Has anyone raised the question of how people like yourself can believe in these hidden codes within the Bible, and yet not in the Bible itself?

Lane: You mean like, “Jesus loves me, this I know [Looks at the audience with skeptically raised eyebrows], for the Bible [Air quotes, returning his gaze to Barashe] tells me so?” [Looks at the audience as they laugh at his wittiness]

Barashe: Yes, exactly.

Lane: My mother used to sing me that song. But you know what? She died in a tragic car accident when I was ten years old, and I finally realized that her faith in this loving God, her truth, was just a myth. Therefore, myth must be truth.

This kind of twisted logic is the basis for the film and snakes its way throughout the whole script. The Beast rises to power by following the secret codes of the Bible, yet we’ve all been warned of it in the books of Daniel, Ezekiel, and Revelation, as other characters make clear. We’re left wondering, “If it was supposed to be so clear to us mere mortals, why did Satan–and that’s really who Michael York’s Stone Alexander is, a possessed megalomaniac–need the secret Bible code to figure out how to bring it all to fruition?”

That’s a question that not only does the film not answer, but it doesn’t even realize it raises it. I suspect this confusion between code and prophecy arises from TBN’s effort to get “real prophecy” into a mass marketed, main-steam film. The popularity of Michael Dorsnin’s The Bible Code and similar books seems to have gotten the writers at TBN to thinking, “Hey, we can use this as a springboard into the Bible’s real code: prophecy!” As a result, it’s a mess.

As a whole, the biggest flaw of The Omega Code is its earnestness. Films usually don’t take themselves as seriously as The Omega Code does, for it not only depicts but is a battle against the wiles of the devil. Yet what the cast and crew end up making, instead of the Biblically-based, thought-provoking thriller they think they’re working on, is a B-movie, and the absolute worst kind: an accidental B-movie. It’s “B” status slipped up unawares, probably just a few moments behind the initial idea was taken seriously by all involved.

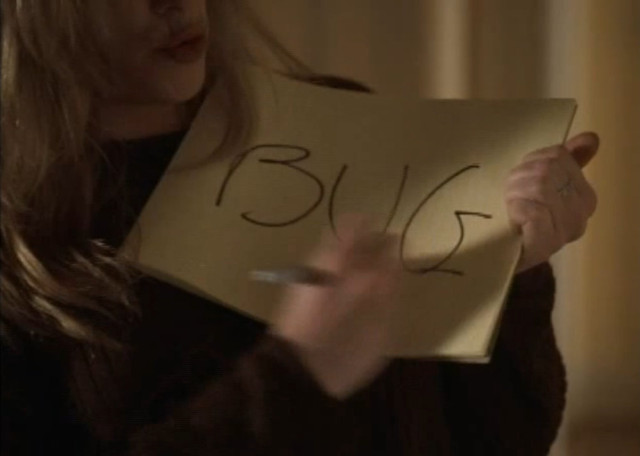

Even if the film were made in earnest but intelligently, it wouldn’t be so bad. But not only are we dealing with an awfully written script, but we’re also enduring characters who are simply stupid. They scribble “bug” on a legal pad to let one another know a room’s wired, then proceed to talk in hushed stage whispers that no known listening device can detect. They run for their lives, literally the most wanted individual on the planet, then start ranting about visions they’re having when they finally find someone who’ll help them.

God bless them all, but they’re freaking idiots, each and every one!

The clear stupidity of the characters lets us sigh in relief, though. In the end, their idiocy transforms the film into a hopeful vision for the future, because if Revelation’s Beast turns out to be half as dimwitted as any one of the characters in this film, there’s hope for humanity.

Unless he starts producing films.

Sysadmin

Value Monkeys

Why is it people with a strong belief in the literal six-day creation of the world seem to take the notion of evolution so personally?

“I didn’t evolve from slime, from monkeys!”

A friend gets a little perturbed when she’s watching something on Animal Planet and evolution is mentioned — as if that completely falsifies anything the particular individual who mentioned the “e word” might have to say.

Of course being offended by it doesn’t make it not true, but that’s beside the point. The point is this: why does where you came from millions of years ago have any affect on your personal value now?

There’s this underlying fear, “If we’re evolved from monkeys, then we can do whatever we want to each other! There is no such thing as rape, murder, etc — it’s all just animal cruelty!”

In this view, humans cannot make values, cannot make meaningful laws. And forgetting the pragmatic side of most laws, these folks promptly jump in their cars and drive to work on the right side (or left, in some countries) of the road…

Pattern of Mate

Chess, from beginning to end, is a game of patterns. Steven Pinker, in The Blank Slate, writes that chess grandmasters are no better than non-players at remembering randomly arranged chess pieces. They rather remember the patterns of threats, attacks, defenses.

Patterns are the stock and trade of autism. Arranging, rearranging, obsessing with shapes.

At school I’ve been finding that chess is in fact an excellent activity for children the higher functioning spectrum of autism. During their choice time, several kids have taken to playing chess, taught primarily by yours truly. Elementary chess; chess without much “strategy”; with some kids, chess without all the pieces (minimizing input and thereby confusion) — still, chess all the same.

Today, much to my surprise, one of the children with more intrusive autism (read: closer to low-functioning than most of the other children) decided he wanted play with the chess pieces during his choice time. He knew that they go one to a square, and he’d even picked up from watching the other kids play during the last few weeks that all the pawns go in front of all the major pieces. Once he’d got them all situated, I asked him if he’d like me to show him how the back pieces were to be arranged. He readily agreed, and I showed him: castles (using “rook,” “knight,” etc. was a level of abstraction that I decided was unnecessary) go on the outside; the horses go next, because they’re riding out of the castles; next we have these tall, funny, pointy looking pieces; and then the king and queen. I tried to get him to turn the board around and set up the white pieces, using the black pieces as a model. Nothing going there, and I simply backed off. I returned in a few minutes to find that he’d done it himself.

Impressive.

But more was to come.

Another young lad decided to join in the fun, and the two were soon having a blast simply moving the pieces around randomly, taking with rooks by jumping three pieces at a diagonal, but still obviously grasping the object of the game.

And then the real shock – the first boy put all the pieces back perfectly and they played again.

Once choice was over, I used the chess pieces and board with the first boy to segue into math, working on which numbers are bigger. Instead of using the workbook and coloring in blocks of a chart to give a visual for the young lad, we used the chess board. Once he’d arranged the correct number of pieces on the board, he then colored in the squares in his workbook, and we had a short little quiz.

“Which number is bigger: six or eight?” A quick to the chess board or the workbook gave him the necessary help when he wasn’t sure. By the time we got to ten (I added two squares on a piece of paper, since a chess board is only eight by eight), he was carefully arranging the pieces by alternating color and size.

And we continued working, without a glitch, even when the rest of the class left for the library.

Mów po polsku!

“Have you ever noticed how few of these children of Polish families actually speak Polish?”

Kinga asked — in Polish, of course — the other evening. She was speaking mainly of the children of a Polish couple who have been in America for more than twenty years, and who rarely if ever go back to Poland as a family. The children of these very nice folk usually speak to their parents in English, even though their parents often simply speak Polish to them.

Kinga and I both want our children to grow up bilingual, but that’s difficult enough when both parents are foreigners. When only one is a foreigner, it might be all but impossible. The language of society dictates what is Language One for the child, and not the language at home.

Where there is a community to support the use of the foreign language, it’s much easier. But North Carolina is no Chicago, and the opportunities to use Polish will be rare.

“We’ll just have to send the kids to Poland every summer,” I replied to Kinga. There’ll be Polish music in the house; we’ll eat Polish cuisine; I’ll try to speak more and more Polish at home; we’ll have Polish books in our library; we’ll just cram Polish culture down their throats! (That is a joke — in reality, there’d be no better way to turn them off of all things Polski.)

Will all that even be feasible, though?

One would think that instilling in them a sense of pride in and love for their heritage would suffice. But at a certain points in their lives, the “un-coolness” of being different would stifle any urge to speak Polish.

Perhaps I’m wrong? Hopefully I’m wrong. We shall just have to read a few books about raising bi-lingual children.

One Thing I Miss About Europe

Adoption and Culture

The other evening, discussion turned to adoption and the supposed population shortage in Europe. The Polish government recently passed a bill that would give families a monetary reward (“aid” was probably the preferred choice of words) for having kids. Kinga answered my protests about unnecessarily adding to the world’s population by saying that she wasn’t sure whether it was a reward for giving birth to a child, or merely having another child (i.e., adoption).

It seems though, that given the number of homeless, neglected children in the world, that there would be a massive effort — in the name of relief at the very least — to get these children adopted.

But what a thorny issue that is, for both the adopter and adoptee.

Most of these kids are in Asia, raising cultural concerns. It’s not just that there don’t seem to be many people willing to adopt kids who don’t look like them. There’s also a question of the child’s culture. If I were to adopt an Indian child, I would want him to have some sense of his heritage – language, food, customs.

There are plenty of studies underway regarding some of the issues raised by adoption. The Transracial Adoption Study “attempts to examine the types of cultural socialization strategies used by parents and to evaluate these as factors in the psychological adjustment of the child.”

In recent years, an increasing number of families have adopted children from other countries. However, there is currently limited research on transracial adoption. As such, this study aims to understand the adoptee experience. The Transracial Adoption Study attempts to examine the types of cultural socialization strategies used by parents and to evaluate these as factors in the psychological adjustment of the child. (Source)

Harvard University’s “Study of Language Development in Internationally Adopted Children” is “looking for families who have recently adopted or will soon be adopting 2.5-6 year old children.”

The complexity of language has bewildered scientists for decades. When adults are trying to learn a new language, they struggle for years to become fluent. Yet young children rapidly acquire language with little apparent effort. At the Laboratory for Developmental Studies at Harvard University, we want to find out how children manage to solve this puzzle and why our abilities change as we grow older. (Source)

But the reality is, most people don’t go this route. Adopting.org writes, for example, that it is possible to adopt a Caucasian baby through a public agency: “Public agencies occasionally have some healthy Caucasian infants. It is worthwhile to inquire about them, but there will probably be a long waiting list” (Source). To adopt a Caucasian baby, agencies look for “couples married at least 1 to 3 years, between the ages of 25 and 40, and with stable employment income.”

And yet if you’re willing to adopt non-white children, the situation is a little different:

For children with special needs, some African-American children, and some intercountry adoptions, agencies are willing to consider single applicants, those over age 40, and those with other children. The adoption of American Indian children by non-lndians is strictly limited by the Federal Indian Child Welfare Act.

Why all this talk of adoption? K and I are hoping, at some point, to adopt at least one child. Being adopted myself, I feel that it would border on immorality for me not to return the gift given to me. But it’s disheartening to see so few people in the world looking at this as a viable option. European governments worried about population and demographics could help solve this problem simply by encouraging families to adopt — say, make the supplement for adopted children higher than for birth children.