Ever wonder what an EFL (English as a Foreign Language) textbook looks like? I certainly did as I was preparing to come to Poland for the first time back in 1996. After all, how often do you get to see a textbook teaching something you already know fluently? Naturally, after four and a half years’ experience, I’ve seen and used more textbooks than I care to remember. I thought I’d share a little about the books I’ve been using.

Ever wonder what an EFL (English as a Foreign Language) textbook looks like? I certainly did as I was preparing to come to Poland for the first time back in 1996. After all, how often do you get to see a textbook teaching something you already know fluently? Naturally, after four and a half years’ experience, I’ve seen and used more textbooks than I care to remember. I thought I’d share a little about the books I’ve been using.

Most units tend to be thematic. For example, for practicing modal verbs such as “should,” “must,” and “have to” (among others), this particular book (and many others) use the idea of advice and “Doing the right thing.”

There are certain groups of easily-confused words, and some activities are aimed at improving students’ ability to choose the correct word from a similar pair. This particular book is written specifically for Polish students, and so that influenced the word choice (in other words, they might not seem like similar words in English, but they are in Polish translation, so . . .).

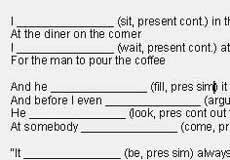

There are three tenses in Polish; there are twelve in English. When to use which tense can be somewhat confusing for students. Even remembering how to make them all can be difficult, so sometimes we have “easy” lessons that just make students think about how to make the tenses. (This particular exercise uses Suzanne Vega’s “Tom’s Diner,” a rather popular song in Poland, making this one of the most popular lessons I’ve ever taught.)

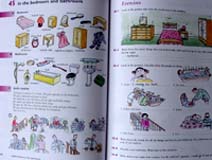

Obviously, the most basic element needed to be able to use a foreign language is an adequate vocabulary.

Teaching English in Poland presented some special challenges. For instance, articles: when to use “a,” when to use “an,” and when to use “the.” Polish doesn’t have articles, so the sentence “Id? do sklepu” could be translated “I’m going to a shop” or “I’m going to the shop.” Teaching students when to use which was initially very difficult.

The most difficult part, though, would be orthography: getting kids to remember that the dark part of a 24-hour period is “night” and a medieval soldier is a “knight” and they’re both pronounced the same.

0 Comments