Growing up, there were a lot of Bibles in our house. All were corrupt translations in one way or another, my father (on the teaching and authority of our little sect) assured me, and it was necessary to read a given passage in a number of different passages to understand it fully.

One of the Bibles we had was the Scofield Reference Bible. Our sect’s leader, Herbert Armstrong, extolled it for its important commentary. It was, in essence, the King James Version with James Scofield’s commentary and explanation.

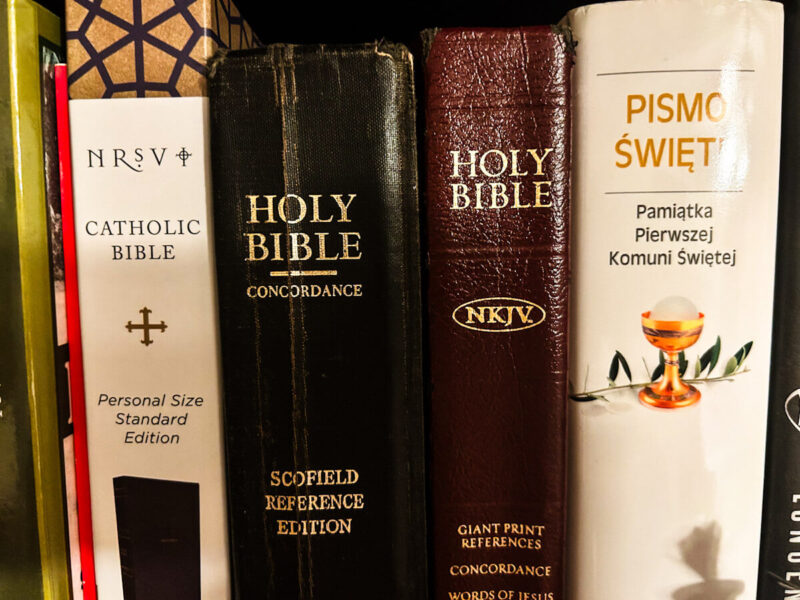

The Scofield was a Bible out of step with what corrupt Protestants and whore-of-Babylon Catholics used. We were the only real Christians on the entire planet, see, and everyone else was corrupt in one way or another. The Protestants liked the King James Version, that’s true, and that was a redeeming point in our eyes, but too many used the Revised Standard Version, or even worse, the liberal New International Version. Like other Christians, we referred to these versions by their initials: the KJV was superior, and the RSV was acceptable, but the NIV was an abomination. Above them all, though, was the Scofield Reference Edition, which I doubted any of my Protestant friends at school had ever heard of.

It turns out, several probably had. It was the favored edition of John Nelson Darby, a nineteenth-century Evangelical who came up with the idea of the rapture, the idea that Jesus would whisk his believers away just before all hell breaks loose on Earth at the end of time. These eschatological ideas come from various places in the Bible. Passages from the Old Testament prophets are mixed with passages from the New Testament epistles of Paul and then folded into the Book of Revelation to produce a horrifying image of the end of the world with something like three-fourths of humans dying in the misery. Scofield’s ideas shaped Darby’s ideas, and the idea of the rapture is a key component of Evangelical Protestants to this day. Most of the pastors serving as “spiritual advisors” to Trump during his first term held to this idea, which is somewhat terrifying: people advising the president were expecting the literal destruction of most of humanity, thinking that they might be playing a part in the prophetic nonsense that leads up to all of that.

Our sect had its own end-of-the-world scenario, but I was always taught that our vision of the future was original and, most significantly, correct. So I grew up not knowing about the idea of the rapture and how Evangelicals interpreted the Bible to create a picture of the end of the word. I certainly didn’t realize how damn similar it was to ours. They even used terms that I thought were exclusive to our correct understanding of the Bible, terms like “The Great White Throne Judgement.”

That’s one thing I’ve learned as I study more about other sects and denominations of Christianity. Far from being unique, our beliefs were an amalgamation of just about every sect out there. Bits and pieces from the Mormons? Check. A little something from the Jehovah’s Witnesses? It’s right there. A touch of good old fashioned Evangelicalism? Got it. Our combination of these things was unique, to be sure, but there was nothing new in anything we believed. Contrary to the assurances of our ministers and leaders, we were not special or unique.

I got to thinking about all of this tonight because of a book by Bart Ehrman I’m reading. Armageddon: What the Bible Really Says About the End takes a scholarly look at the Book of Revelation and traces the history of some of the ideas modern Christians root in that book — like the rapture. Suddenly I was reading about the Scofield Reference Bible, something I hadn’t thought about in decades.

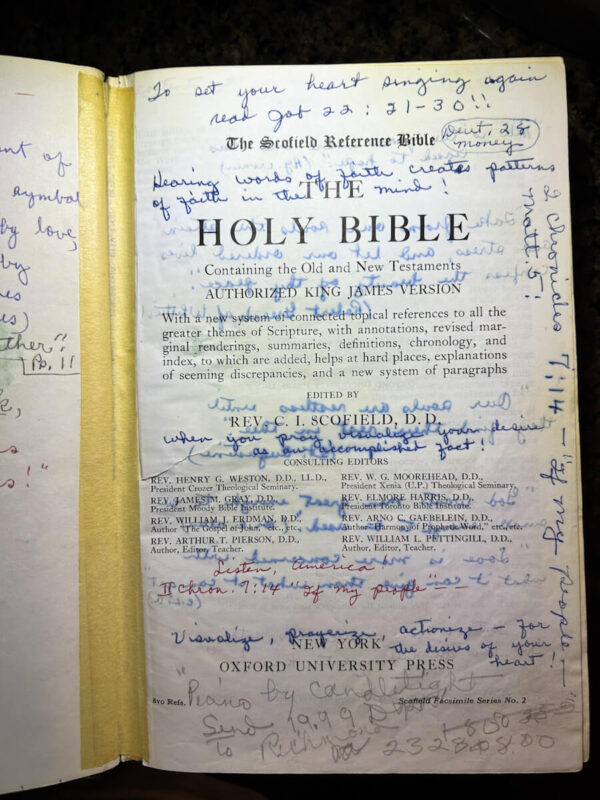

Papa’s was in a leather cover with a zipper, and he had covered countless pages with endless annotations. When Papa moved in with us, we got rid of most of his Bibles (his choice — “How many do I really need?”), but I found myself wondering if we still had his Scofield. I walked into his old room, looked at the top row of his bookshelf where I knew the Bibles lived.

And there was a Scofield.

“I don’t think that’s his, though,” I thought, remembering the leather cover. I opened it and saw it was covered in annotations. “But that’s not Papa’s writing,” I realized. Sure enough, on the inside cover: Ruby Williams, Nana’s mother. She wasn’t a member of our sect. In fact, I think she rather disliked it. But she was an Evangelical and so shared a preference for the Scofied.

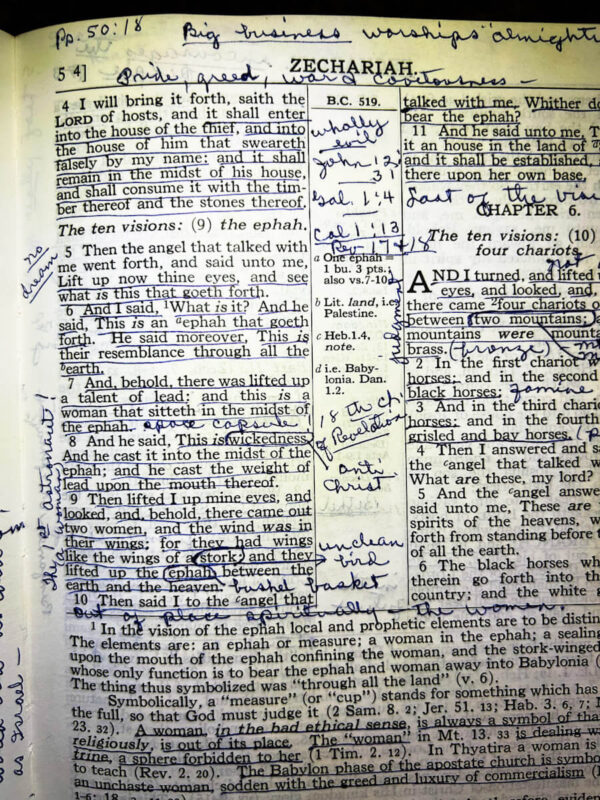

The annotations themselves are fascinating. On one page, there are all the signs of the interpretative practices we borrowed from Evangelicalism.

“The Bible is a jigsaw puzzle!” Herbert Armstrong, our sect’s founder and leader, taught countless times. One had to piece together bits from here and bits from there to see the true picture. In serious (i.e., scholarly) study of the Bible, there’s a term for this: proof-texting. The idea is simple: if you take bits randomly from the Bible (i.e., get your proof from throughout the text), you can prove anything.

On the above page of text from the Old Testament prophetic Book of Zechariah, we see my grandmother connected it to the Book of Revelation (chapters 17 and 18) as well as Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians (chapter 1 verse 4). The vast majority of the text is underlined to indicate its importance.

And along the foot of the page, the reason for everyone’s love (or hatred) of this particular edition: James Scofield’s commentary. He patiently explains that “Symbolically, a ‘measure’ (or ‘cup’)” is something that’s full and “God must judge it.” These are not usual study notes for a Bible. It’s not explaining some ambiguities of the original Hebrew. It’s not discussing the translation difficulties of a given term. It’s telling readers what this particular passage symbolizes. It is interpreting the Bible, putting ideas in readers’ heads that really don’t come from the Biblical text but rather from Scofield’s vision of the whole sweep of Biblical history.

Along the top, we also see it connected to contemporary social commentary: “Big business worships ‘almighty dollar.'” On that single annotated page is the story of the Evangelical approach to the Bible, and while it would have pained me to admit it as a child (who doesn’t want to be special? called out? unique?), it is the story of our interpretative technique as well.