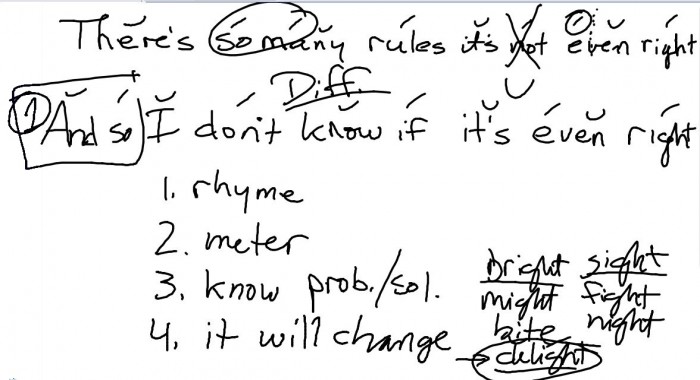

Driving back from Orlando today, I got to thinking again about the writing project I’ve been considering, and I came up with yet another organizational idea for it. Indeed, not just another organizational idea, but a somewhat altered focus. So two initial drafts get shoved aside for a third. Fortunately, I was only a few thousand words into the other two drafts, so there’s no real loss there. I’m excited about the new approach and began jotting notes on my phone as I took the dog for a walk.

But the whole way, I think the Girl relived the highlights of competing in nationals.