It usually happens in the opposite direction: Slovaks come to Poland for the relatively cheap goods here. Twenty years ago, Poles went to Slovkia, but now that has reversed since Slovakia adopted the Euro. However, Babcia likes bucking trends, I think, so today we went, as we always do during our stay her, on a shopping trip to Trstena, the nearest town in Slovakia.

Every time we go into Trstena, Babcia waxes romantic. She goes on and on about how she loves the town, about how there’s so little traffic compared to Jablonka, how there are so few plastic, awful sign attached to every available surface.

It is a unique little town: you can stand in the middle of the town square and just behind a few buildings see the farming fields.

It’s a sliver of town in the middle of vast fields of grains and grasses.

It’s a small town, but there are a couple of churches and several restaurants.

It’s easy to see how a small town could support two churches — at least in the past. But so many restaurants? There can’t possibly really be any industries around here, one thinks. And then one remembers the fields surrounding the town. And who knows — perhaps they are like their neighbors just across the border and go abroad to work.

We started with the shopping. Babcia is convinced that Slovakian flour is better than Polish flour, so we bought an almost unbelievable amount of flower. The next item we bought in large amounts was Slovakian rum. Slovakia is not exactly the first country that comes to mind when thinking of rum, but Babcia swears by it. Finally, we almost emptied the store of the grill rub that makes chicken wings magical for the Girl.

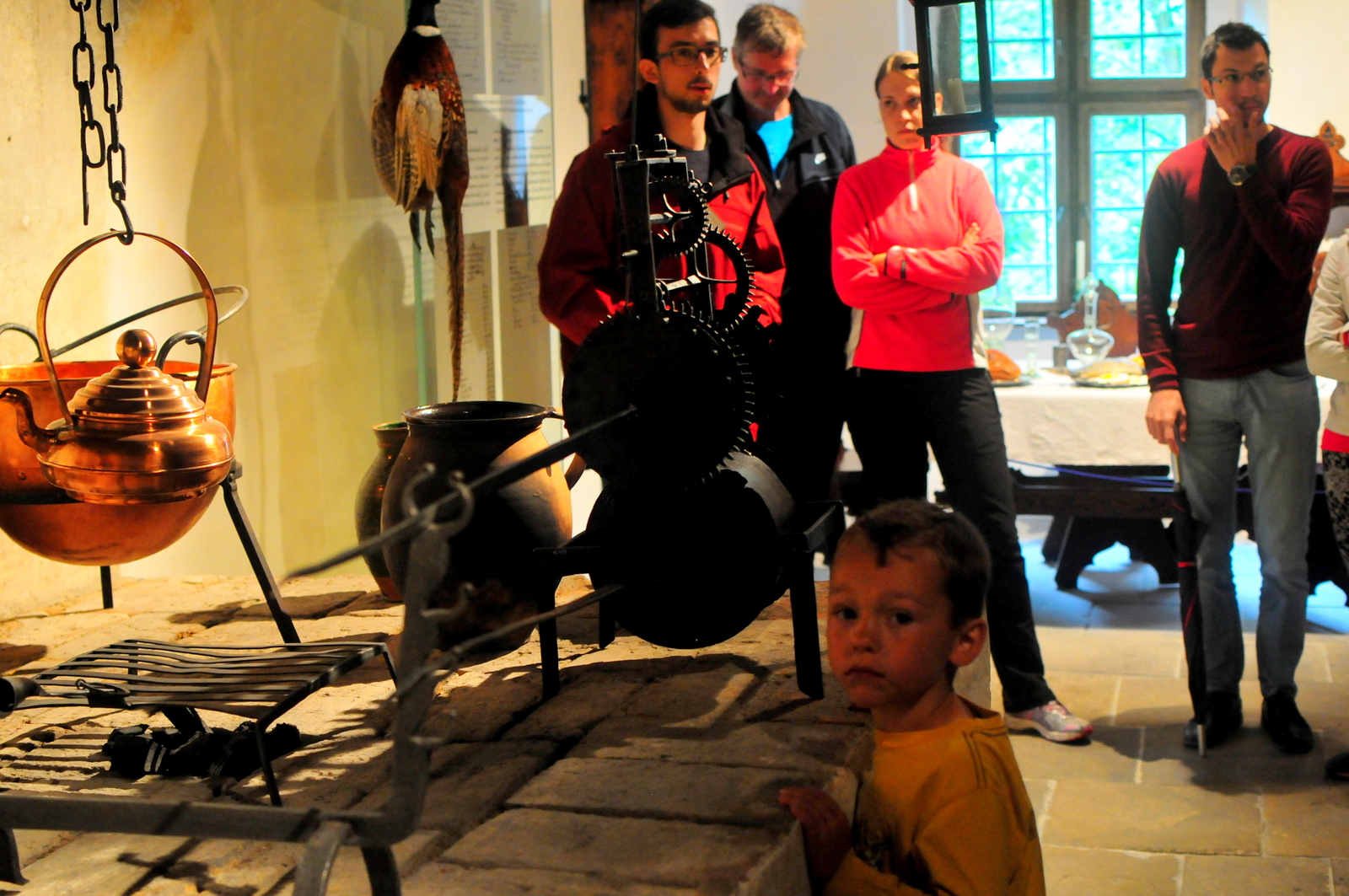

A fourth (or is it fifth? or third?) visit to Oravsky Hrad. This time, a few changes. A simplified camera set up to accompany a simplified tour due to the ages of our tourist. And a few random thoughts that unwound along the way.

In the crypt of the chapel at Orava Castle there are three coffins, two small ones and a large one. The tour being in Slovak and only partially comprehensible to me, I’m not sure if I understood it all, but I believe the two coffins are those of one owner’s children, an eight month old and a four year old. I had one of those moments: I remember what family life used to be, even for the riches and most fortunate. Infant mortality was unbelievably high (compared to now), and even living past five or six was not assumed. Having children might mean burying them before they were a year old, and it might mean burying multiple children. They could have died for any number of diseases that have now been virtually eradicated through improved hygiene, a better understanding of disease and its transmission, and effective vaccines. Yet for them, each child’s death was something of a mystery. Sure, they recognized and categorized diseases based on symptoms, but the actual cause was a mystery, as was any possible prevention.

And so I am grateful that I live in a time when protecting my children against measles, for example — a potentially fatal disease that, according to the WHO, would have resulted in “an estimated 20.3 million deaths” between 2000-2015. I’m grateful that I live in a time when I can take my child to the doctor and get a diagnosis and medication to help the child. I’m grateful that I’ve never once wondered whether my children will die of measles or small pox before they turn five. As I looked at the smallest casket, I felt fairly sure that her parents would have given almost anything to have that kind of security.

Orava Castle was the set for Nosferatu, a 1922 film adaptation of Dracula. I remember hearing that the idea of a blood sucking tyrant came from Vlad the Impaler. Here was a man who could do just about anything to just about anyone and became famous for a particularly brutal way of killing. He seems to be the exact opposite of what we have in most countries in the Western world today, where the rule of law treats everyone — theoretically — the same. Anyone from a homeless person to the President of the United States can be subject to the same law.

Yet what is most surprising about Vlad is that he was a real law-and-order guy. While there were plenty of people who were killed for arbitrary things, a great number were killed due to transgressions of Vlad’s severe moral code.

Further, Vlad was involved in fighting the Turks and preventing the spread of Islam in Europe. Despite his brutality, he was considered an orthodox Christian, and the Pope had little to nothing to say about his viciousness. He was, after all, fighting the Turks — the rest is insignificant, right?

When the Turks’ invasion began overwhelming Vlad’s forces, he began a scorched-Earth policy, destroying villages on both sides of the Danube to slow the Turks’ progress. This meant destroying his own people in vast numbers.

And so I began thinking about how we take this for granted today. We don’t raise our children wondering whether or not our own leader is going to slaughter them trying to save his own power. We don’t have to fear our rulers’ whims because they are subject to the same laws we are.

Tour Guide

Oravský Hrad

Morning: a trip to Slovakia to do some shopping. Babcia explained that the flour there is much better quality and that the crocheting thread is much cheaper, so we headed to Trstena, the first real town across the border.

Despite all the changes in Lipnica and Jabłonka, Trstena really hasn’t changed all that much. The town square still looks more or less like it did the first time I went in 1996. Sure, there have been a few updates in architecture, but mainly face-lifts to get ride of the old socialist realism of the previous era.

We made our purchases and then found a cozy restaurant for a bit of lunch. And of course since we were in Slovakia, there was only one thing on my mind for lunch: bryndzové halusky. I could eat the stuff by the kilo if it weren’t for the fact that it’s a complete fat and carb bomb.

Since Babcia wanted to stop and get some trash bags — the local trash collecting agency will only pick up trash and recyclables that are in the proper bag, in typical bureaucratic fashion — and since the bags are available only in one location, we decided to drive around Lake Orawa and come at Lipnica, where the trusty bags are located, from the backside. This meant we went over the dam that formed the lake some decades ago and prompted the creation of the town of Namestovo for the displaced residents of the valley. Of course, the boy loved it.

Part two: Nowy Targ. K had some shopping to do and wanted to get her hair done, and since two people recommended the same hairdresser in NT, there was only one place to go. I on the other hand had other things on my mind: no trip to Poland is complete without a visit to C, the Other American in the area with whom I spent countless weekend hours in the late 90s.

A quick walk over the river and through the cemetery and soon, C and I were catching up, reminiscing.

K came by, showed off her lovely new hairstyle, and chatted with us a bit before we turned back toward Jabłonka.

In some ways, nothing special about today’s events. Had today been eighteen years ago, it would have been almost typical — not for a Tuesday, perhaps, but maybe for a Friday or Saturday. All it takes to turn the typical into the extraordinary then is eighteen years and a few thousand miles.

It’s obvious almost instantly that you’ve crossed the border into Slovakia. Everything looks similar, but just different enough. The villages above all: stretched out along a single road, houses huddled up to the street, house after house looking quite similar.

Today’s fieldtrip, Oravský Hrad — Orawa Castle, just about forty kilometers inside Slovakia but a world away from the twenty-first century. Probably the third or fourth time I’d been there, but when I’d shown L pictures of the castle — instant intrigue.

And who wouldn’t be intrigued with a castle literally perched on the razor tip of a high cliff?

Yet I was a little worried about the legs of our smallest visitors: it begins with a climb and only grows steeper through the visit. Up, up, up — anyone with any fear of heights needs not apply, nor anyone with weak legs.

Having seen for the first time a couple of years ago the film 1922 Nosferatu, I was particularly interested in the first couple of gates. While none of the interiors were used for the film, the exteriors framed the early adaptation of Dracula.

In 1922 none of the interiors had yet been renovated, but if they had, there are a few interiors that certainly would have served the film well.

As for today’s visit, the interiors seemed less interesting than the exteriors. And most fascinating was the mannequin dressed as Count Orlok, the vampire antagonist from Nosferatu.

“Tata, is that real?” And it was a fairly terrifying sight.

“Why does he have claws?” little D asked.

“What is that?” S asked.

I explained to everyone about the film, and honestly, I thought they would continue to worry about it, to fret about it. But soon enough, they were crowded around the mannequin.

A small victory for adult common sense in children.

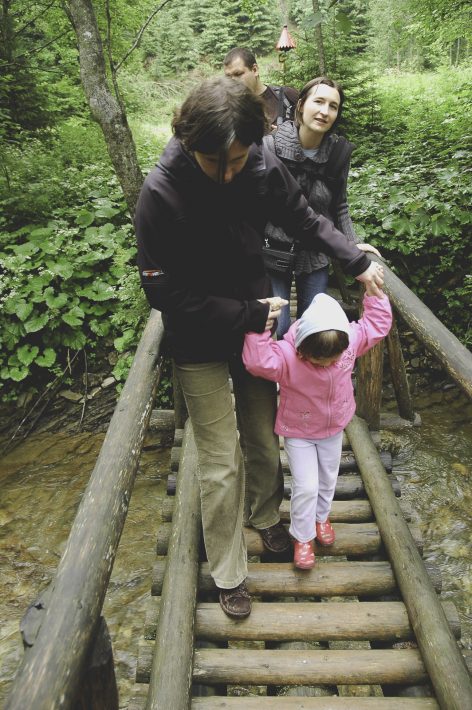

It wasn’t supposed to rain. “Bedzie pogoda,” everyone says, which is oddly appropriate when literally translated. A word-for-word translation is, “Will be weather”; a less literal reading: “There will be weather.” It seems a little odd: there’s always weather. Still, it’s synonymous with “There will be good weather.”

“Bedzie pogoda.” Not quite. But at the very least, “Bedzie spacer…”

And there will be signs. With two little girls under the age of five, we had to turn it into a game. Easy enough: let’s look for the path marks.

And so off we went. The sequence was simple.

Adult: “I see one.”

Children: “Where?! Where!?”

There were plenty of places they didn’t look but I did — not for signs of course. For something less concrete, literally and figuratively.

In some ways, shooting in heavily overcast conditions is easy: it makes one look less at the sky and thus focus on the things at hand. On the other hand, the light can be, at best, tricky.

Given the wet, slippery conditions, I wasn’t the only one looking down instead of looking up.

Yet the hunt for the signs continued. Through the forest, through the meadow, we looked for the elusive marks. When they became obvious (striped stakes driven into the ground beside the path), the girls become somewhat blind to them.

But the moment of discovery was as exciting for us as the girls.

But for a great deal of the time, it was just walking. As the lingering droplets on the grass made our pants increasingly wet, it started to become a question of plodding.

Finally, we got to the forest, and the “almost” plodding became pure plodding as we slogged our way through mud and up hills, the girls on shoulders or strapped to one’s back.

Once we got back onto the paved path — an oxymoron? — the frustration lifted, as did the clouds.

By the time we returned home, the sun was breaking through the clouds.

It sort of figures.

Technically, this post is a day late. And I should be talking about our amazing walk in the Tatra Mountains. But that’ll come tomorrow. In the meantime, Monday’s adventures.

We can’t come to southern Poland and not cross over into Slovakia. It’s beautiful, and cheaper.

First stop: Namestovo.

Namestovo is odd because it doesn’t really have a square as much as it has an L.

Slovaks, like many Europeans, think nothing of a beer with friends at 10:30 in the morning. I think it’s more common the further east one travels, but I do seem to remember reading about folks in Spain having brunch with a beer.

We walked around for just long enough for us all to be surprised that it was already 12:00. Lunch — and swings.

Everyone else was talking about what to eat — well, K was talking to the two kids who can express their desires verbally — but I knew from the moment we decided to spend the day in Slovakia: bryndzowe halusky.

Basically, it’s dumplings in a creamy sauce, with this particular version having bacon bits and onions added. Smooth, tangy, creamy — I could eat a bucket of this stuff!

I’ve already told K that we’ll have to cross the border once more for a second helping!

Afterward, it was time to take the kids on a boat ride.

Lake Orawa is an artificial lake. Beneath its waters lie four villages.

In the middle of the lake stands an island with the only surviving remnants of antediluvian Orawa.

A surprisingly-large church that’s been converted to a museum. (We took Nana and Papa here, before they were “Nana” and “Papa”. It was a gloomy day in comparison.)

On the way back, we got a good look at Namestovo.

Odd — it’s now a lake-front town; pre-flood Namestovo would have been a mountain-top town.

It had always been my understanding that Namestovo more or less was created for the relocation of all those displaced by the creation of the lake. K assures me that it’s not, and there’s no mention of it in Wikipedia. Besides, K made a great point about communist architecture at the time: “Come on — if it had been all built at once, every building would have been identical.”

When we returned to shore, we took a few pictures. It’s fairly obvious the two youngest cousins are getting along swimmingly.

It’s hard to believe that, despite the similarity in size, Cousin S is over a full year older than L. “She’s a brick,” everyone says.

On the way back, we stopped in Bobrov — the Slovakian last town on the Slovakian/Polish border when you cross the border at Winiarczykowka, the small border crossing at Lipnica Wielka.

I’d cycled this way countless times when I lived in Poland. Of course, they’ve redone the road in the meantime, which would have made my favorite ride even better: by the time I got to the end of this road on a road bike, I often had to take a break, not because I was tired but because my forearms ached from riding over such a rough road

We also got a clear indication of just how rural this area is:

The view from the Polish side of the border wasn’t much different.

Borders are such strangely arbitrary things. This area is particularly odd. There are masses in Slovakian in the church in Jablonka, yet Slovakian cuisine is really radically different than Polish, even at the borders. The languages are similar (Poles tend to think Slovakian sounds like Polish baby-talk) but the mentalities are different.

When we got home, it was time for the youngest cousins to complete their evening rituals.

The cartoon they were watching is a Czech cartoon about a little mole who has various adventures with rockets and pregnant rabbits. (He helps birth three rabbits in a rather graphic scene.)

As I said, they’re getting along swimmingly.