Ever wonder what an EFL (English as a Foreign Language) textbook looks like? I certainly did as I was preparing to come to Poland for the first time back in 1996. After all, how often do you get to see a textbook teaching something you already know fluently? Naturally, after four and a half years’ experience, I’ve seen and used more textbooks than I care to remember. I thought I’d share a little about the books I’ve been using.

Ever wonder what an EFL (English as a Foreign Language) textbook looks like? I certainly did as I was preparing to come to Poland for the first time back in 1996. After all, how often do you get to see a textbook teaching something you already know fluently? Naturally, after four and a half years’ experience, I’ve seen and used more textbooks than I care to remember. I thought I’d share a little about the books I’ve been using.

Most units tend to be thematic. For example, for practicing modal verbs such as “should,” “must,” and “have to” (among others), this particular book (and many others) use the idea of advice and “Doing the right thing.”

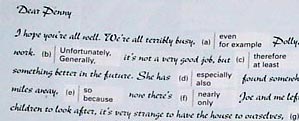

There are certain groups of easily-confused words, and some activities are aimed at improving students’ ability to choose the correct word from a similar pair. This particular book is written specifically for Polish students, and so that influenced the word choice (in other words, they might not seem like similar words in English, but they are in Polish translation, so . . .).

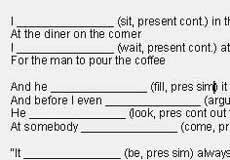

There are three tenses in Polish; there are twelve in English. When to use which tense can be somewhat confusing for students. Even remembering how to make them all can be difficult, so sometimes we have “easy” lessons that just make students think about how to make the tenses. (This particular exercise uses Suzanne Vega’s “Tom’s Diner,” a rather popular song in Poland, making this one of the most popular lessons I’ve ever taught.)

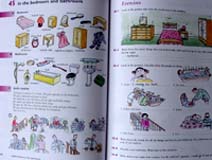

Obviously, the most basic element needed to be able to use a foreign language is an adequate vocabulary.

Teaching English in Poland presented some special challenges. For instance, articles: when to use “a,” when to use “an,” and when to use “the.” Polish doesn’t have articles, so the sentence “Id? do sklepu” could be translated “I’m going to a shop” or “I’m going to the shop.” Teaching students when to use which was initially very difficult.

The most difficult part, though, would be orthography: getting kids to remember that the dark part of a 24-hour period is “night” and a medieval soldier is a “knight” and they’re both pronounced the same.

There are quite a few who go to daily mass. It’s mainly elderly women, judging from the small stream of people I see leaving the church. This raises a question: how does one draw the line between sincerity and habit? And what if it seems only to be habit despite the individual’s protests that it’s not? Pious until proven habitual? Or maybe I’m begging the question of them being mutually exclusive.

There are quite a few who go to daily mass. It’s mainly elderly women, judging from the small stream of people I see leaving the church. This raises a question: how does one draw the line between sincerity and habit? And what if it seems only to be habit despite the individual’s protests that it’s not? Pious until proven habitual? Or maybe I’m begging the question of them being mutually exclusive.

Vodka accounts for many of the little surprises I’ve noticed around here — missing fingers, for instance. Many men in Lipnica have part or all of one or more fingers missing. I knew fairly early on that this would be a result of carelessness in one of the many sawmills in the village, but I thought, “Come on, simple carelessness doesn’t account for it.” Then I saw a man covered with wood chips and sawdust come into a shop and buy a half-liter of vodka.

Vodka accounts for many of the little surprises I’ve noticed around here — missing fingers, for instance. Many men in Lipnica have part or all of one or more fingers missing. I knew fairly early on that this would be a result of carelessness in one of the many sawmills in the village, but I thought, “Come on, simple carelessness doesn’t account for it.” Then I saw a man covered with wood chips and sawdust come into a shop and buy a half-liter of vodka. As far as straight drinking goes, though, Poles, while they out-drink Americans to a lip-numbing degree, are teetotalers in comparison to Russians. I once saw a documentery in Poland, called Z?ota Ryba (“The Golden Fish”), about vodka in Russia. It showed a home distillary that produced 140 proof (i.e., 70% alcohol) vodka that even Grandma was tossing back by the full glass (Not a shot glass, mind you, but the size Poles use for coffee and tea.), without a chaser.

As far as straight drinking goes, though, Poles, while they out-drink Americans to a lip-numbing degree, are teetotalers in comparison to Russians. I once saw a documentery in Poland, called Z?ota Ryba (“The Golden Fish”), about vodka in Russia. It showed a home distillary that produced 140 proof (i.e., 70% alcohol) vodka that even Grandma was tossing back by the full glass (Not a shot glass, mind you, but the size Poles use for coffee and tea.), without a chaser.

I’ll never forget the first time I saw it: standing in a shop at seven in the morning, waiting to buy something for breakfast, I watch a man come in, buy a beer, down it in one long gulp (for lack of a better word), put the bottle on the counter and walk out. Seven in the morning.

I’ll never forget the first time I saw it: standing in a shop at seven in the morning, waiting to buy something for breakfast, I watch a man come in, buy a beer, down it in one long gulp (for lack of a better word), put the bottle on the counter and walk out. Seven in the morning.

The concept was simple: why not use snow skiing as a model for water skiing? It would eliminate the necessity for need for a boat, thus allowing more people the pleasure of waterskiing in a shorter time.

The concept was simple: why not use snow skiing as a model for water skiing? It would eliminate the necessity for need for a boat, thus allowing more people the pleasure of waterskiing in a shorter time. Now, it’s not an entirely bad idea. Just, for someone used to skiing behind a boat, it’s a little weird. I passed on trying. Most didn’t.

Now, it’s not an entirely bad idea. Just, for someone used to skiing behind a boat, it’s a little weird. I passed on trying. Most didn’t.

I did buy D’Adario strings once here — they lasted probably three months. Yes, that’s a ridiculously long time for strings, but how often would you change them if they cost forty bucks? Anyway, they sounded dead as a brick by that time, but they were still intact. None of them had broken, or even frazzled.

I did buy D’Adario strings once here — they lasted probably three months. Yes, that’s a ridiculously long time for strings, but how often would you change them if they cost forty bucks? Anyway, they sounded dead as a brick by that time, but they were still intact. None of them had broken, or even frazzled. Then I’ll trek back to Nowy Targ, buy a new set of strings, and kick myself for not buying decent ones in the first place.

Then I’ll trek back to Nowy Targ, buy a new set of strings, and kick myself for not buying decent ones in the first place. Few things seem to cause as much angst in a Polish teenager’s life like the matura: a series of compulsory written and oral exit exams. Required of all students are two exams from Polish: a written and a spoken test. Students must pass the written before they are allowed to take the oral exam.The written matura consists of four essay questions read aloud at precisely 9:00 a.m. on the same day in high schools throughout Poland.

Few things seem to cause as much angst in a Polish teenager’s life like the matura: a series of compulsory written and oral exit exams. Required of all students are two exams from Polish: a written and a spoken test. Students must pass the written before they are allowed to take the oral exam.The written matura consists of four essay questions read aloud at precisely 9:00 a.m. on the same day in high schools throughout Poland. This year the questions included the interpretation of a Wis?awa Szymborska poem, and a question, “Od Adam i Ewy…” (From Adam and Eve), about the loss of one’s home and one’s place in society as illustrated through literature. Another question began, “If you want to know a person, look at his shadow…”

This year the questions included the interpretation of a Wis?awa Szymborska poem, and a question, “Od Adam i Ewy…” (From Adam and Eve), about the loss of one’s home and one’s place in society as illustrated through literature. Another question began, “If you want to know a person, look at his shadow…”