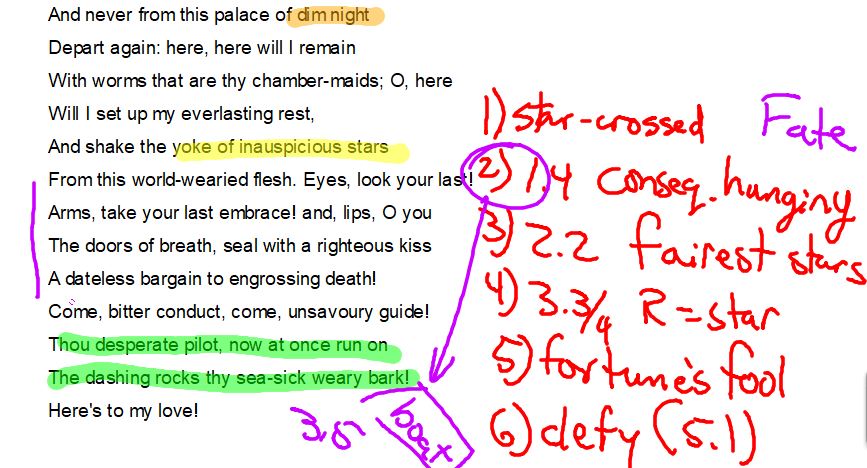

We looked at the final soliloquy in the play, when Romeo loses all sense of rationality and makes a horrible decision based primarily on emotion. We examined how Shakespeare develops this idea within the text by

- extensive use of “O”;

- chaotic changes in the soliloquy’s subject;

- references to a loss of control;

- and other techniques.

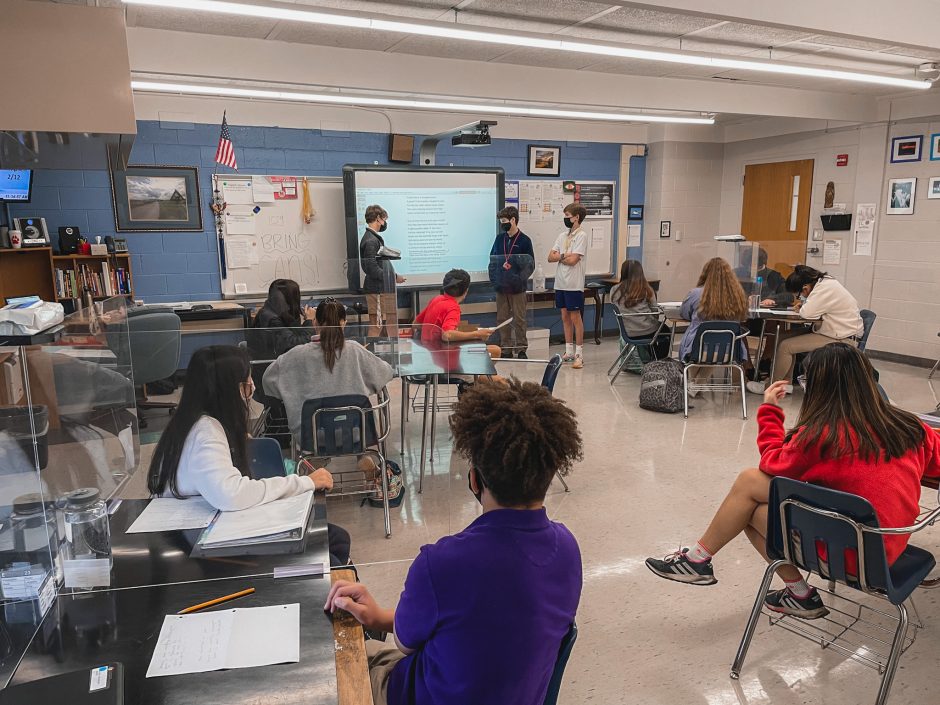

Students first presented their claims about the text, many of which led naturally into the observations I wanted students to have later in the lesson.

They were doing some pre-teaching for me, in other words.

It was a good day to be a teacher.