Fear and Faith

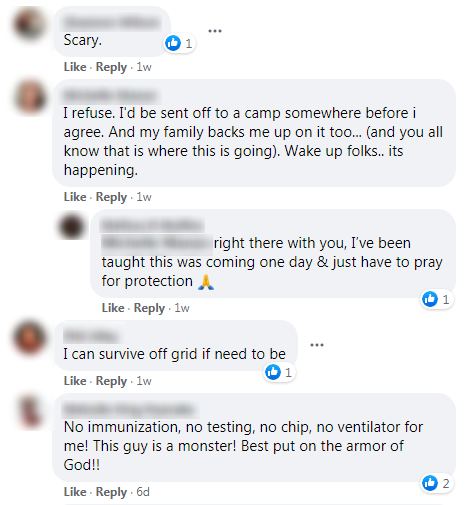

Imagine fear nestled into anxiety burrowed into terror, and all of that is supposed, in the end, to be a source of great joy. “In my beginning is my end” T. S. Eliot wrote, but for some evangelical Christians, it might be reworded, “In my anxiety is my comfort,” for they view their everyday reality through an apocalyptic lens. They post things like this on social media:

The single comment “Scary” reveals the paradox at the heart of this line of thinking.

On the one hand, there is a sense of terror at what’s coming. Such believers look at the Bible as a roadmap for the future, seeing all sorts of ideas that, to those of us on the outside looking in, seem patently ridiculous. They see a coming world-engulfing violent cataclysm that will wipe out wide swaths of humanity and subject the survivors to near-slavery under the rule of some world-dominating ruler known simply The Beast, who will rule in what they call The Tribulation. During this time, there will be mass executions of believers and worldwide oppression.

At this point, the vision starts fracturing. What will happen to Christians, to good Bible-believing Christians who saw all this coming and gave themselves over to the Lord long ago? Some suggest that these poor Christians will have to go through all this; others (most) believe firmly that they’ll all be whisked away to heaven before all this — the rapture.

I grew up being taught that, like the rapture, God would supernaturally protect all his faithful Christians from this onslaught of literal hell on earth, but instead of being taken away into heaven, we would escape to a location of protection, which got the name the Place of Safety. Our religious leader conjectured it would be in Petra, Jordan. There we would spend the three-and-a-half years that the devil, through his Beast, would rule and torment the world, emerging at the end when Jesus returns to put the devil in his place and us in charge of rebuilding the world. Sounds crazy — but not any crazier than being whisked away like the Left Behind book series narrates.

Whatever the belief, though, these groups have one thing in common: the believers — the right-believing faithful — will be saved. This, then, should be a time of joy for such Christians. The end is almost here, and because they believed the right things all these times, they won’t have to endure the horrors coming.

So why the fear? Just look at the thoughts that follow the original “Scary” comment:

These poor folks are genuinely scared about Bill Gates’s supposed plans to use this pandemic and the resulting vaccine, which they fear will be mandatory (which it should be), to implant chips into them.

There is an amusing irony in all this, though:

“The COVID-19 vaccine is a trick so they can put a tracking chip in your body!” they furiously tweet out from the tracking device they willingly carry everywhere in their pocket.

— Faith Naff 🏳️🌈🏳️⚧️🌹🦋 (@FaithNaff) May 9, 2020

Such a strange mix of confusion, and it’s driving thousands upon thousands to outright terror.

There is, of course, one thing that these fear-stricken Christians can do: they can pray about it.

Yet what is the effectiveness of this prayer? This verse from the Bible promises that “if my people, who are called by my name, will humble themselves and pray” that God “will heal their land.” If that doesn’t sound like a promise from omnipotence that is directly applicable to our current situation, I don’t know what does.

But we’ve tried this before:

— Richard Dawkins (@RichardDawkins) April 4, 2020

These Christians will point out that there are conditions: the petitioners must “turn from their wicked ways” before this promise will be fulfilled, so that’s probably the problem: America is still aborting pregnancies, fornicating, and tolerating homosexuality (the three biggies), so God is just waiting for that to stop.

On March 30 televangelist Kenneth Copeland must have decided he would not wait for the stubborn, God-hating Americans to repent and simply “exercised judgment” on the pandemic, thus ending it:

But four days later, he realized he had to try again:

And yet it’s still not over.

Here’s where another layer of anxiety enters: these poor souls must be wracking their brains and souls trying to figure out what they’re doing wrong. So it seems to me that this type of Christianity does not relieve anxiety but only heightens it. Instead of these beliefs calming you, they add another layer of anxiety when one’s prayer’s and petitions are either ignored or answered in the negative, and the natural response is to blame oneself: “God promised. I must have done something wrong.”

So by the time we get to this level, we have the following fears, some conscious and some less so.

- The end of the world is literally around the corner. If I’m right with God, I’ll be spared. Am I right with God?

- Even if I’m right with God, my interpretation of end-time prophecy might be a little wrong and Jesus might not return until after the tribulation. So if I go through this horror, how will I know I’ll be spared in the end?

- I know God doesn’t always answer prayers, but his Word says he will if I repent and pray, so if I or someone close to me becomes infected, I’ll pray, but it might not be his will.

- And even if it is his will, I might have done something wrong. Or my country might be doing something wrong.

For something that’s supposed to bring comfort, that’s an awful lot of sources of anxiety.

In a sense, these folks have a right to their anxiety. The First Amendment guarantees that right. But some of these anxiety-inducing conspiracy theories have long-reaching effects. They lead people to reject science for religious-based superstition:

Right-wing pastor Curt Landry tells his follower never to accept any eventual coronavirus vaccine because it’s a set-up for the Mark of the Beast: “That vaccine is from the pit of Hell. Do not pray for those vaccines, and do not take the vaccine. ” https://t.co/4oExoRqTbJ pic.twitter.com/OdePBeRaT1

— Right Wing Watch (@RightWingWatch) April 2, 2020

Conspiracy theories have been around for ages, and fundamentalist Evangelical Christians have often been particularly willing to believe them. After all, their whole religion is a conspiracy theory: the devil is constantly trying to get humans to do his bidding unknowingly. The group I grew up in went so far as to call itself the only group of true Christians in the world: the rest of the “so-called” Christians were actually worshipping a Satan-created replacement Christianity. These “so-called Christians” were, for all intents and purposes, worshiping the devil himself. But even among the milder, less cultish groups, there is a sense of conspiracy. Indeed, this conspiracy goes all the way back to the Garden of Eden, when the devil tried to usurp God’s control over humanity.

I’m certainly not the only one to notice this similarity:

Arthur Jones, the director of the documentary film Feels Good Man, which tells the story of how internet memes infiltrated politics in the 2016 presidential election, told me that QAnon reminds him of his childhood growing up in an evangelical-Christian family in the Ozarks. He said that many people he knew then, and many people he meets now in the most devout parts of the country, are deeply interested in the Book of Revelation, and in trying to unpack “all of its pretty-hard-to-decipher prophecies.” Jones went on: “I think the same kind of person would all of a sudden start pulling at the threads of Q and start feeling like everything is starting to fall into place and make sense. If you are an evangelical and you look at Donald Trump on face value, he lies, he steals, he cheats, he’s been married multiple times, he’s clearly a sinner. But you are trying to find a way that he is somehow part of God’s plan.”

So we’re at the point that we’re all living in different realities. The Atlantic has an article about this now: “The Prophecies of Q,” aptly summarized, “American conspiracy theories are entering a dangerous new phase.”

The power of the internet was understood early on, but the full nature of that power—its ability to shatter any semblance of shared reality, undermining civil society and democratic governance in the process—was not. The internet also enabled unknown individuals to reach masses of people, at a scale Marshall McLuhan never dreamed of. The warping of shared reality leads a man with an AR-15 rifle to invade a pizza shop. It brings online forums into being where people colorfully imagine the assassination of a former secretary of state. It offers the promise of a Great Awakening, in which the elites will be routed and the truth will be revealed. It causes chat sites to come alive with commentary speculating that the coronavirus pandemic may be the moment QAnon has been waiting for. None of this could have been imagined as recently as the turn of the century.

Would could imagine a scenario in which a prankster began something like Q and then it quickly gets out of hand. The prankster tries to step forward and point out that he began it all. “Look, I have evidence!” He could have even had the foresight to record everything he did on video and through screen-recording software, yet that wouldn’t be enough once the conspiracy had gained a life of its own. One can only imagine what such a prankster would feel as he watched his creation ravage reasonable — a modern Frankenstein, with the conspiracy theory being his unnamed monster.

Yet Frankenstein could reason with his creation, and in fact did attempt to talk to him. Conspiracy theories are like memes: they’re elements of the brain that are belong to no one and are somewhat self-replicating. In short, there’s no reasoning with a conspiracy theory, and there’s little ability to talk to a believer in one:

Taking a page from Trump’s playbook, Q frequently rails against legitimate sources of information as fake. Shock and Harger rely on information they encounter on Facebook rather than news outlets run by journalists. They don’t read the local paper or watch any of the major television networks. “You can’t watch the news,” Shock said. “Your news channel ain’t gonna tell us shit.” Harger says he likes One America News Network. Not so long ago, he used to watch CNN, and couldn’t get enough of Wolf Blitzer. “We were glued to that; we always have been,” he said. “Until this man, Trump, really opened our eyes to what’s happening. And Q. Q is telling us beforehand the stuff that’s going to happen.” I asked Harger and Shock for examples of predictions that had come true. They could not provide specifics and instead encouraged me to do the research myself. When I asked them how they explained the events Q had predicted that never happened, such as Clinton’s arrest, they said that deception is part of Q’s plan. Shock added, “I think there were more things that were predicted that did happen.” Her tone was gentle rather than indignant.

There’s no reasoning with them because they often don’t even see themselves as conspiracy theorists:

“Some of the people who follow Q would consider themselves to be conspiracy theorists,” [David] Hayes[, one of the best-known QAnon evangelists on the planet] says in the video. “I do not consider myself to be a conspiracy theorist. I consider myself to be a Q researcher. I don’t have anything against people who like to follow conspiracies. That’s their thing. It’s not my thing.”

So in the end, it’s hard not to be at least somewhat depressed about all this, and that in turn tends to make me just a little pessimistic about our future as a species — yet again. I can help our children develop the critical thinking skills (the painfully basic critical thinking skills) to avoid falling into this trap themselves, but that’s two in a nation of millions. These ideas are gaining momentum, and the alternative cultures they spawn are growing.

Fun

The Boy and I went out exploring again today. He had to try his new gumboots. I warned him about deep water: “If the water goes over the top of the boot, your foot will be permanently soaked.” He stepped in water that was too deep. One foot got soaked. We laughed quite a while about the squishing sounds coming from his boot.