This is from about a year ago, but it is very much worth the time it takes to watch it. And anyone who watches this and is not terrified on some level…

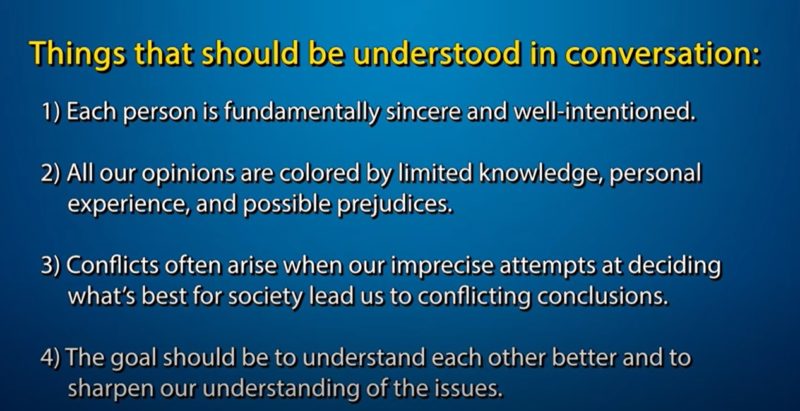

At the heart of this, Jeremiah Jennings (who goes by the name Prophet of Zod on social media) points out that functioning society involves discussing disagreements with people while holding a few assumptions in mind:

He then goes on to point out, very convincingly, how fundamentalist Christianity doubts or even outright disputes each of these claims. The implications this civic breakdown has for democracy are frightening.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0lqaqp5TwnU

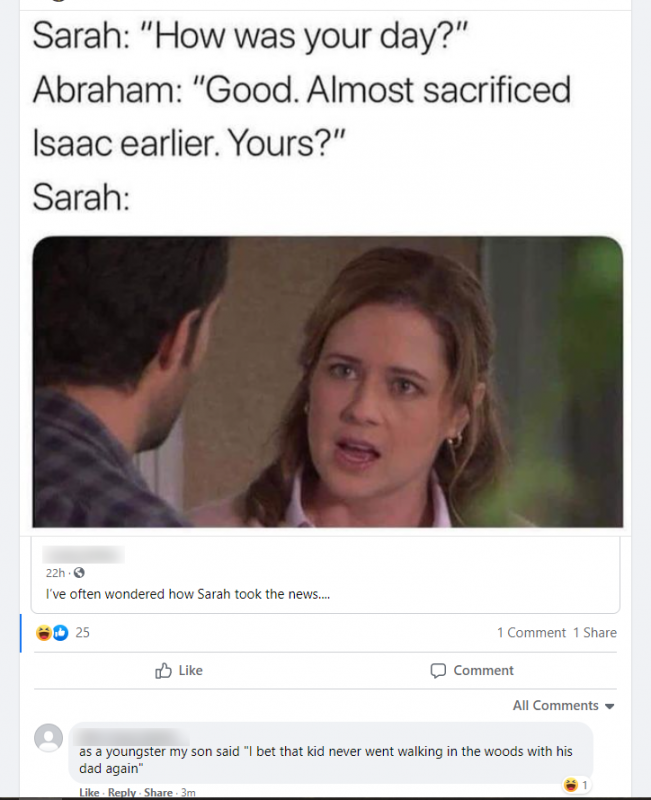

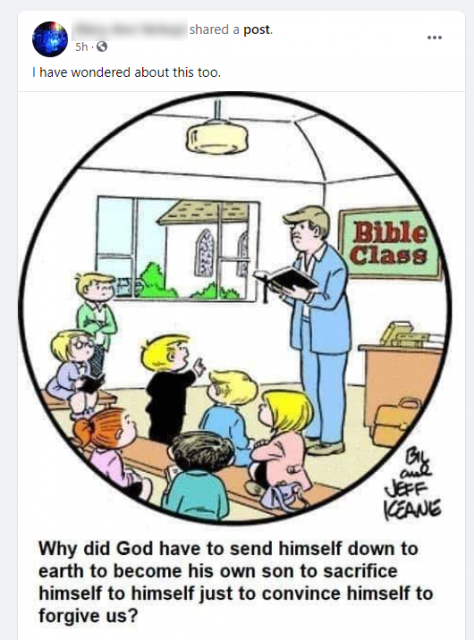

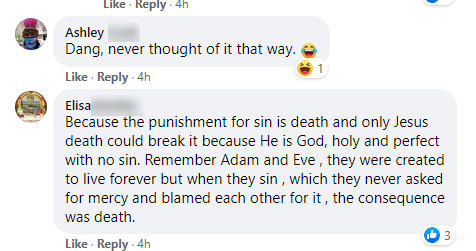

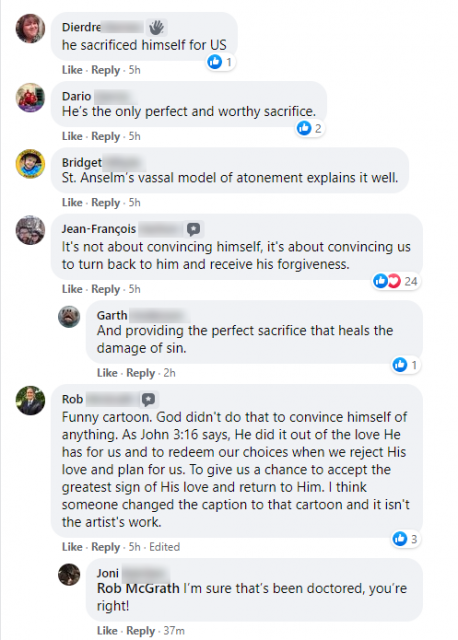

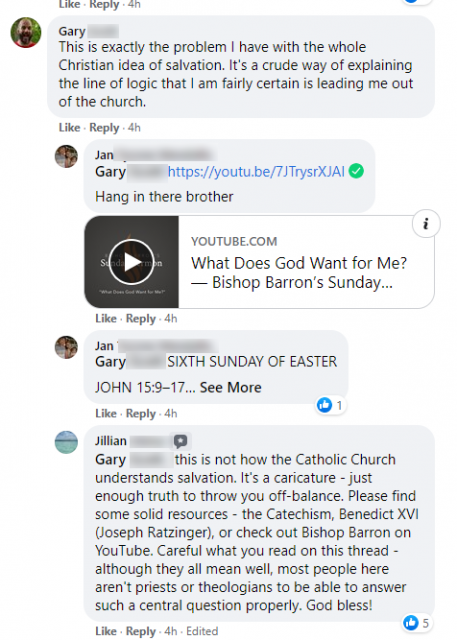

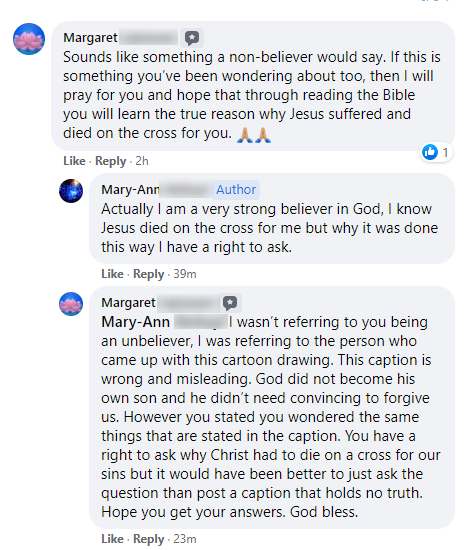

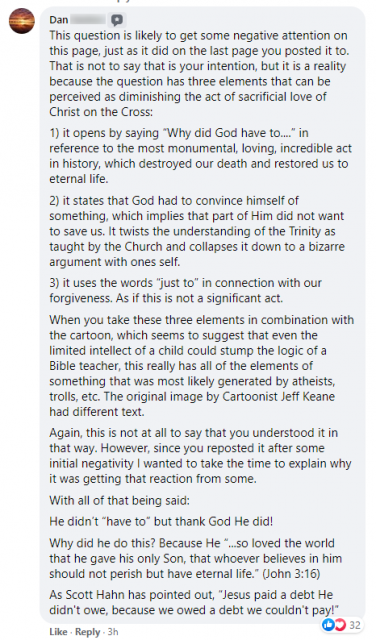

We see what we want to see. Social media offers the best example of that in the contemporary world, but sometimes, it’s not just evident in a macro-view but in individual postings.

We see what we want to see. Social media offers the best example of that in the contemporary world, but sometimes, it’s not just evident in a macro-view but in individual postings.