I’ve been reading Faulkner and thought it might be fun to emulate him. Forgive me.

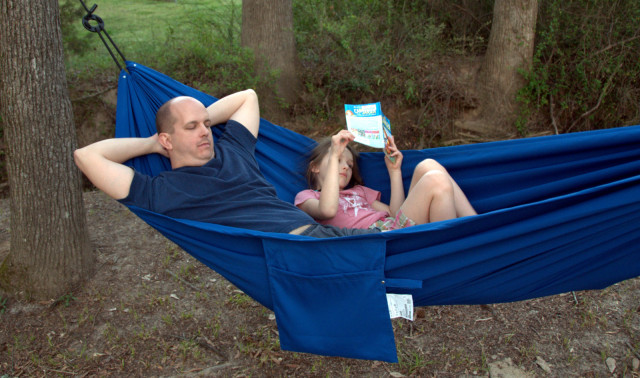

Having cleaned up after dinner, a process that entails both the obvious cycling of dishes back to the dishwasher only hours after having taken them out to hide them neatly in stacks concealed behind cabinet doors only to place them on the table yet again in and endless cycle that is the bane of our children’s existence and the not so obvious assisting Papa in his regimen of oral hygiene procedures foisted on him by childhood dental neglect, a regimen that has become a comforting habit rather than a chore, we head out for our evening walk, a Covid-19-induced habit that might be the best outcome of a worst-case scenario. Tired of the usual routes, we’ve taken to walking a circuit that runs through the neighborhood just across from ours, a newer neighborhood without power lines snaked between crooked power poles but not so new as to have sidewalks, a neighborhood with a slightly more eclectic mix of architecture. For about a year now this has been our favorite route, in part because K likes the feel of the neighborhood more than others, in part because of its distance — almost exactly a mile — and in part because of the long, straight, flat stretch that it includes where the kids, L on her rollerblades and E on his bike, play a strangely frustrating version of tag that includes time outs and random rules that E is convinced — and I am likely to agree — are L’s on-the-spot inventions intended to keep her from being tagged.

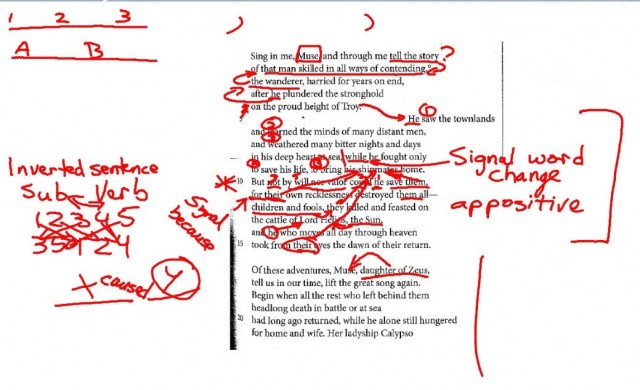

Enough — how that man could write like that, though what I did was just a pale imitation, lacking the lugubrious flourish he put into every sentence as if it were the habit of a card cheat. See? Once you start writing like that, start thinking like that, once you start piling phrase upon phrase, clause upon clause, it’s almost impossible to stop, so maybe that’s how he did it: just a big push and off he went, heedless of periods, question marks, semicolons, and anything else resembling in its vaguest form something that someone could accuse of being an ending, a final mark on the paper to suggest “Stop.” The result, in all seriousness, is nothing short of breathtaking. His greatest achievement, Absalom, Absalom!, just sings right from the opening sentences.

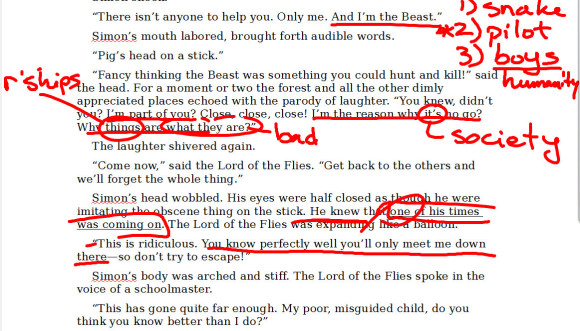

From a little after two o’clock until almost sundown of the long still hot weary dead September afternoon they sat in what Miss Coldfield still called the office because her father had called it that-a dim hot airless room with the blinds all closed and fastened for forty-three summers because when she was a girl someone had believed that light and moving air carried heat and that dark was always cooler, and which (as the sun shone fuller and fuller on that side of the house) became latticed with yellow slashes full of dust motes which Quentin thought of as being flecks of the dead old dried paint itself blown inward from the scaling blinds as wind might have blown them. There was a wistaria vine blooming for the second time that summer on a wooden trellis before one window, into which sparrows came now and then in random gusts, making a dry vivid dusty sound before going away: and opposite Quentin, Miss Coldfield in the eternal black which she had worn for forty- three years now, whether for sister, father, or nothusband none knew, sitting so bolt upright in the straight hard chair that was so tall for her that her legs hung straight and rigid as if she had iron shinbones and ankles, clear of the floor with that air of impotent and static rage like children’s feet, and talking in that grim haggard amazed voice until at last listening would renege and hearing-sense self-confound and the long-dead object of her impotent yet indomitable frustration would appear, as though by outraged recapitulation evoked, quiet inattentive and harmless, out of the biding and dreamy and victorious dust. Her voice would not cease, it would just vanish. There would be the dim coffin-smelling gloom sweet and oversweet with the twice-bloomed wistaria against the outer wall by the savage quiet September sun impacted distilled and hyperdistilled, into which came now and then the loud cloudy flutter of the sparrows like a flat limber stick whipped by an idle boy, and the rank smell of female old flesh long embattled in virginity while the wan haggard face watched him above the faint triangle of lace at wrists and throat from the too tall chair in which she resembled a crucified child; and the voice not ceasing but vanishing into and then out of the long intervals like a stream, a trickle running from patch to patch of dried sand, and the ghost mused with shadowy docility as if it were the voice which he haunted where a more fortunate one would have had a house.

Four sentences weighing in at just a little over 400 words, with three of the sentences doing most of the work: that third sentence is so perfectly short (“Her voice would not cease, it would just vanish.”) that it creates the perfect rhythm, a little pause in the thinking that gives both authenticity to the voice and rest to the reader.

I’m reading Absalom now, probably for the tenth or twelfth time, and each time I read it, I notice a little something that had escaped my attention previously: some little piece to the puzzle (for the book is, at its heart, a puzzle to match the puzzle that is living itself), some lovely phrase, some little something. I don’t think I will ever tire of that book, and every time I finish it, I look forward eventually to starting it again: “From a little after two o’clock until almost sundown of the long still hot weary dead September afternoon they sat in what Miss Coldfield still called the office…”

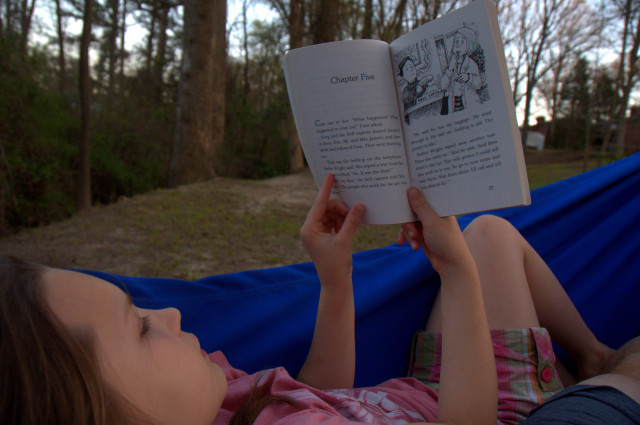

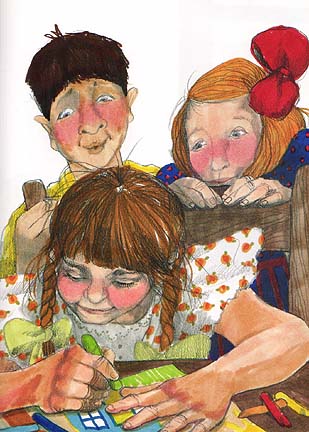

Every year, as we begin a unit on the Gary Paulsen novel Nightjohn, I read Patricia Polacco’s Thank You, Mr. Falker. The story of a young dyslexic girl who was suffering the taunts of peers and the seeming neglect of teachers, the book emphasizes the life-changing nature of literacy. Trisha, the protagonist, spends the first four grades of school hiding her inability to read, feeling dumb for not being able to keep up with peers, and taking solace in her one skill, her exceptional artistic ability. It’s such a touching story that even a room of rowdy eighth-graders ends up sitting in silence, visibly moved. Every now and then, a girl — always a girl, for a boy will never show such a “vulnerability” — sniffles in the back or wipes her eye occasionally as the story nears its conclusion.

Every year, as we begin a unit on the Gary Paulsen novel Nightjohn, I read Patricia Polacco’s Thank You, Mr. Falker. The story of a young dyslexic girl who was suffering the taunts of peers and the seeming neglect of teachers, the book emphasizes the life-changing nature of literacy. Trisha, the protagonist, spends the first four grades of school hiding her inability to read, feeling dumb for not being able to keep up with peers, and taking solace in her one skill, her exceptional artistic ability. It’s such a touching story that even a room of rowdy eighth-graders ends up sitting in silence, visibly moved. Every now and then, a girl — always a girl, for a boy will never show such a “vulnerability” — sniffles in the back or wipes her eye occasionally as the story nears its conclusion.

When I start a favorite book with a class, I recall the weeks I was a tour guide for my folks and best friend from high school, all of whom flew to Poland for K’s and my wedding.

When I start a favorite book with a class, I recall the weeks I was a tour guide for my folks and best friend from high school, all of whom flew to Poland for K’s and my wedding.