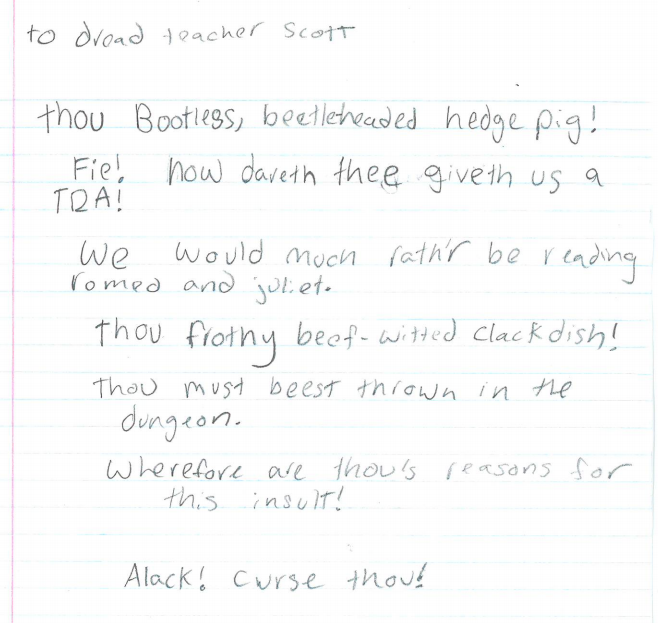

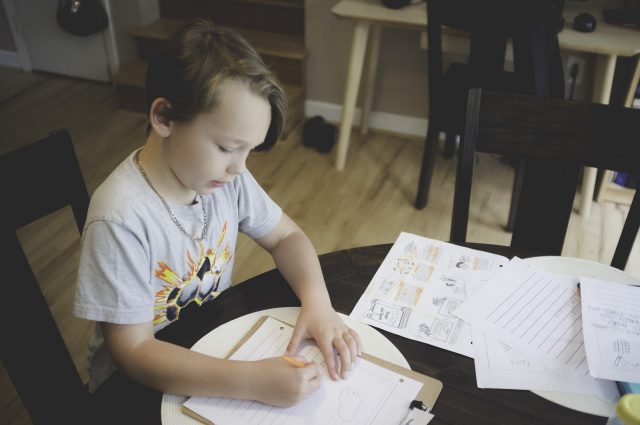

When teachers throughout South Carolina became significantly concerned that the state might ban, among other things, 1984, I’m sure I wasn’t the only teacher who thought, “Now, when was the last time I read that? I should probably reread it.” However, I just reread it a few years ago, and while I love re-reading favorite books, enough time has to pass between reading to make it enjoyable. It occurred to me, though, that, books becoming increasingly worrisome to the powers that be, I might like to read it to the Boy. I knew the Girl had already read it, but the Boy — it’s not a book he would read himself. Truthfully, though, he is a bit young for it. So I decided we’d do the next best thing: read Animal Farm.

We’ve been reading a chapter every few nights, and I’ve used it to teach the Boy a bit about the history underlying that fable. Tonight we read chapter 8.

A few days later, when the terror caused by the executions had died down, some of the animals remembered-or thought they remembered-that the Sixth Commandment decreed “No animal shall kill any other animal.” And though no one cared to mention it in the hearing of the pigs or the dogs, it was felt that the killings which had taken place did not square with this. Clover asked Benjamin to read her the Sixth Commandment, and when Benjamin, as usual, said that he refused to meddle in such matters, she fetched Muriel. Muriel read the Commandment for her. It ran: “No animal shall kill any other animal without cause.” Somehow or other, the last two words had slipped out of the animals’ memory. But they saw now that the commandment had not been violated; for clearly there was good reason for killing the traitors who had leagued themselves with Snowball.

I told the Boy about the Stalinist purges, especially the Great Terror of 1937. I told him about Solzhenitsyn and some of the anecdotes he relates in The Gulag Archipelago. The Boy was shocked?

“Why did they do that?”

“To maintain power.”

Napoleon was now never spoken of simply as “Napoleon.” He was always referred to in formal style as “our Leader, Comrade Napoleon,” and this pigs liked to invent for him such titles as Father of All Animals, Terror of Mankind, Protector of the Sheep-fold, Ducklings’ Friend, and the like. In his speeches, Squealer would talk with the tears rolling down his cheeks of Napoleon’s wisdom the goodness of his heart, and the deep love he bore to all animals everywhere, even and especially the unhappy animals who still lived in ignorance and slavery on other farms. It had become usual to give Napoleon the credit for every successful achievement and every stroke of good fortune. You would often hear one hen remark to another, “Under the guidance of our Leader, Comrade Napoleon, I have laid five eggs in six days”; or two cows, enjoying a drink at the pool, would exclaim, “Thanks to the leadership of Comrade Napoleon, how excellent this water tastes!”

I told the Boy about all the titles bestowed upon Stalin, all the awards, all the honorifics.

“What did Stalin try to do, then?” I asked.

“Make himself into a god.” A bit simplistic, but not too far from the truth.

I explained the illogical thinking behind the claim that atheism is behind the most horrific events of the twentieth century because China and the Soviet Union were officially atheistic states. “They had the exact same dogmatic belief structure as the strictest religion,” I explained.

In the late summer yet another of Snowball’s machinations was laid bare. The wheat crop was full of weeds, and it was discovered that on one of his nocturnal visits Snowball had mixed weed seeds with the seed corn. A gander who had been privy to the plot had confessed his guilt to Squealer and immediately committed suicide by swallowing deadly nightshade berries. The animals now also learned that Snowball had never-as many of them had believed hitherto-received the order of “Animal Hero First Class.” This was merely a legend which had been spread some time after the Battle of the Cowshed by Snowball himself. So far from being decorated, he had been censured for showing cowardice in the battle. Once again some of the animals heard this with a certain bewilderment, but Squealer was soon able to convince them that their memories had been at fault.

I explained to the Boy the idea of saboteurs in Soviet ideology: all the shortcomings of state-run enterprises (i.e., most of what happened in the USSR) were explained away by the idea of enemies of communism undermining the efforts of the Soviet government to create a utopia.

I can’t help but see parallels in all of this with the MAGA cult. Just as the pigs were gaslighting the animals about the changes going on around them, Trump lies opening to his followers, and the true MAGA devotees, blinded by their devotion to Trump, don’t even see the obvious inconsistencies and lies. Just as Napoleon’s and Stalin’s sycophants praised them with honorifics and virtual worship, so too the MAGA commitment to promoting Trump in literally messianic terms. Just as Squealer and the other pigs convince the animals to disbelieve their own memories, Trump’s campaign brazenly called on his supports to cast Harris as a threat to democracy while painting the man who literally led an attempted insurrection as the savior of all.

Our country is about to be in a mess that might not be fully cleaned up by the time the Boy is nearly my age, and he needs to know it has happened before and will happen again.