Overcoming

“I did give up.”

The Girl was upset with ourself for not having completed the line course she had begged — absolutely begged — to complete. The longest. The most challenging.

K tried to talk her out of it, and the whole time the Girl was on the course, she was like this:

Of course there was no real risk: tourists are secured at all times on a security line with not one but two safety ropes. Still, both the Girl and her mother were somewhat frightened by the whole thing. And then there was the exhaustion: K tried this course some years ago and was unable to complete it. Her arms and hands gave out. She was hesitant to continue after the first obstacle, but went on anyway. L had exactly the same experience. Then came an especially challenging rope section, and K’s arms just gave out. But L kept on going, with much encouragement.

The last two obstacles seemed hardly to be obstacles to me: two long zip lines. And it was there that the Girl just gave out.

Afterward, the conversation: I tried to express how proud I was of her, how proud she should be of herself, that she completed so much of the course.

“You wanted to stop, but you didn’t. You kept going, when you were tired, when you were scared. You didn’t give up.”

“I did give up.”

Can you give up and not give up at the same time? I think so.

Somehow the Girl exposed a truth about giving up and going on. It’s a step-by-step basis. It’s a step-by-step battle. And every step that overcomes fear or exhaustion is itself a victory.

The Boy had his own adventures.

Celebrating Babcia

Calls wishing all the best and visitors throughout the day.

Playing Wojna with Babcia

The Day After

A typical day in the country can be positively relaxing after such a fast-paced trip. The morning might include a store or two, and everything always seems to orbit the kitchen.

There’s a lot of snacking, of course, because there’s always something to eat, something tempting like fresh cherries and strawberries or miodownik.

By lunchtime, I’d only made it to 1,300 steps, which was about the same number I took every morning to walk to our beloved bakery in Warsaw for breakfast pastries.

After lunch, the Boy went out to help Babcia around the yard with a bit of digging, a bit of sawing. He dug a big hole at the end of Babcia’s flower bed and explained, “When it rains, all the water will go there, and that will help the flowers. I don’t know how, but it will.”

Babcia got to chopping wood to start the evening’s fire for hot water, I lugged about 150 kg of coal toward the same goal (though my coal was for several days or even weeks of water), and the Boy continued digging.

And where was the Girl? She’d gone to reunite with a friend from two years ago. This upset the Boy, but he refused to go when Babcia had taken L for the the visit despite the fact that there would be a boy his age there. He’s always been a little shy at first, and we might have to wait a week or two before he’s willing to go play with strangers. Or maybe not: he’s always doing something unexpected, socially speaking.

When it was time to retrieve the Girl, we all headed out for a walk. The Girl, it turned out, wasn’t there. “They’ve gone out for a bike ride,” the big sister told us.

We headed out without her, only to meet her returning.

“Where are you girls going?”

“To Babcia’s, to make slime.” We brought Elmer’s glue just for that aim. Like fidget spinners, it’s the rage among L’s friends. “Here too,” A told us when she visited us our first night in Warsaw. And there’s a small change: things happen here and there at the same time. It used to be that it took some time for a fad to cross the ocean, but the internet has shrunk the world.

The Girls headed off to make slime; we continued to the river.

It didn’t take much of a commitment to make today a rest day, by and large.

Transient

On the way to and from shopping, two babcias stopped for a short, transient chat.

Neighbors

Every trip to Poland, the kids get crazy about some cartoon series or other. One year it was the Russian cartoon series “Nu Pogodi.” This trip, it’s the old Czechoslovakian stop-motion series called “Sasiedzi” (“Neighbors”) in Poland. Good stuff.

W-wa Addendum

In the last little bit of time we had this morning before heading to Warszawa Centralna, I investigated the Google Maps marking just behind our apartment complex. Noyzk Synagogue, which my American friend told me over lunch the other day was the last operating functioning synagogue in Warsaw. It was easy enough to find, but more for me, in a way, were the placards around it. One indicated a small street just a couple of blocks over: ulica Próżna. The only remaining street of the Warsaw Ghetto after the Uprising. A truly historic street.

I made it to the end of the street and turned right on Zielna street and found something completely unexpected: signs in Polish and Yiddish.

And just beside this small Jewish district — did I mention I saw a man walking down the street wearing a yarmulke and chatting on his phone in Hebrew? — a new Jewish theater is under construction.

K and I were wondering what Warsaw might have looked like had it not been leveled. There still would have been one difference if Hitler had left Warsaw standing: the Jewish culture of the city would still be only a memory.

Perhaps it won’t always be just a memory, though.

Back in the south, though, (and what a journey that was)

we’re reminded that, though it’s great to see other parts of Poland, there’s no place like Babcia’s.

W-wa Day Five

We’ve had a couple of lazy days now, but our last day we were determined to pack as much into it as possible. That’s how it seems looking back over the pictures of the day, but in fact, we really only had one major item — the Warsaw Uprising Museum — and the rest was just improvisation. I’ve learned during our time in Warsaw, though, that if there’s any city open to improvisatorial sightseeing, it’s this one.

Uprising Museum

Was it worth it? A last-ditch effort to overthrow the grip of a brutal dictator from the West encouraged by the vague promises of an equally brutal dictator from the East — in hindsight, wasn’t it destined to fail? Surely the Poles knew that they couldn’t trust anything Stalin said. Certainly the Poles didn’t think the Germans would let such violent insubordination just disappear as a footnote in history. So why do it?

That’s hindsight. In reality, it was probably at the same time simpler and more complicated for that. For the individual “soldiers” fighting for Poland in the Uprising — and I use quotes certainly not in any negative sense — it was a chance to level the game. Death had touch everyone by then, and it probably didn’t take a lot of convincing to get the average male Pole to take up arms. There were many likely thinking, “We’re all going to die from this occupation anyway. We might as well take some Germans down with us.”

But those ultimately calling the shots in London, the government in exile — did they have a hard time making that decision? Did they honestly think that anything could come of it? Were they blinded by patriotic war-time zeal for revenge? Or was it something more? Or less? I really don’t know enough about the Uprising to do more than raise those questions, and the museum does a good job of raising those questions. But I’m not quite sure that was its goal.

There was one portion of the museum that left me a little frustrated. In a passage leading from one portion to the other were exhibits of the modern Polish army, with video footage of men disassembling and assembling various weapons, taking part in exercises, discussing missions in Iraq and Afghanistan. It really felt like an advertisement for the army. I’ve nothing against that, but it seemed a little out-of-place there in a museum about the Uprising. Perhaps it was a not-so-subtle statement that something like that won’t happen again.

One would hope not.

Lunch

We had to eat at one of those ulta-hip, ultra-modern restaurants while in Warsaw, where you really pay a ridiculous amount of money for a ridiculous amount of food.

“We’re going into a restaurant that’s little more, well, everything than where we normally go,” I explained to the kids.

They got it.

Mostly.

Dom Sierota

K and L recently listened to a Polish kids book about Korczak and his orphanage. It really didn’t go into any details about the tragic yet in some ways beautiful ending of the story; instead, it just went over the revolutionary way Korczak ran his home, with kids making the rules, meting out punishments, cooking and cleaning.

The fact that he marched with his kids to the trains that took them to their deaths in Treblinka was left out, I think. It’s not a topic for a kids book, the author must have thought. Yet there’s a beauty in that: he had several opportunities to escape. People tried to convince him to go into hiding. Yet he refused.

Much to our surprise, the site is still an active orphanage. It turned out to be quite close to the museum, so before lunch, we headed over to find it.

It was haunting to watch my children play on the grounds of that orphanage. Every time E is scared, I ask him, “What’s my job?”

“To protect me,” he replies without hesitation.

Can I always do that? In pre-war Poland, was that possible? What if I was overcome with consumption and K, too? How could we then protect our children? What if we were imprisoned by an occupying power because of our religion or ethnicity and then systematically murdered? How could we then protect our children? It made me wonder if that’s a bit of a lie. A well-meaning lie, a statement that we have every intention of preventing from slipping into falsehood, but ultimately a lie all the same?

Naturally, one can’t function thinking that way, and we all live our lives as if nothing tragic is going to happen to us.

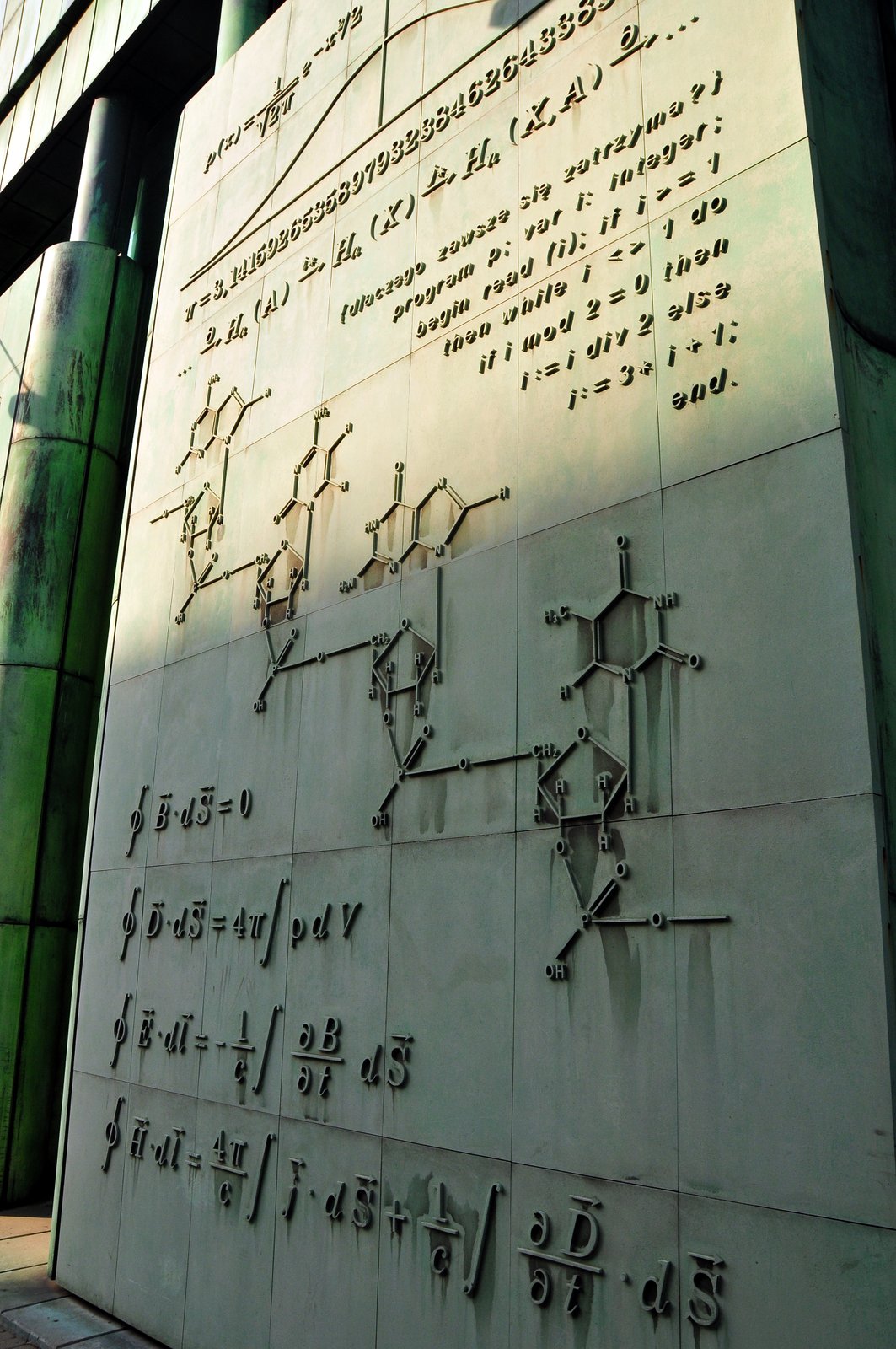

University of Warsaw Library

After lunch, we headed back toward the river so we could try the University of Warsaw Library again.

Two things were different this time: first, the wicker basket swing — for lack of a better term — was unoccupied, so the kids headed straight for it.

(E yesterday said, “That looks like a bee hive.” All the adults looked at it, thought for a moment, and agreed.)

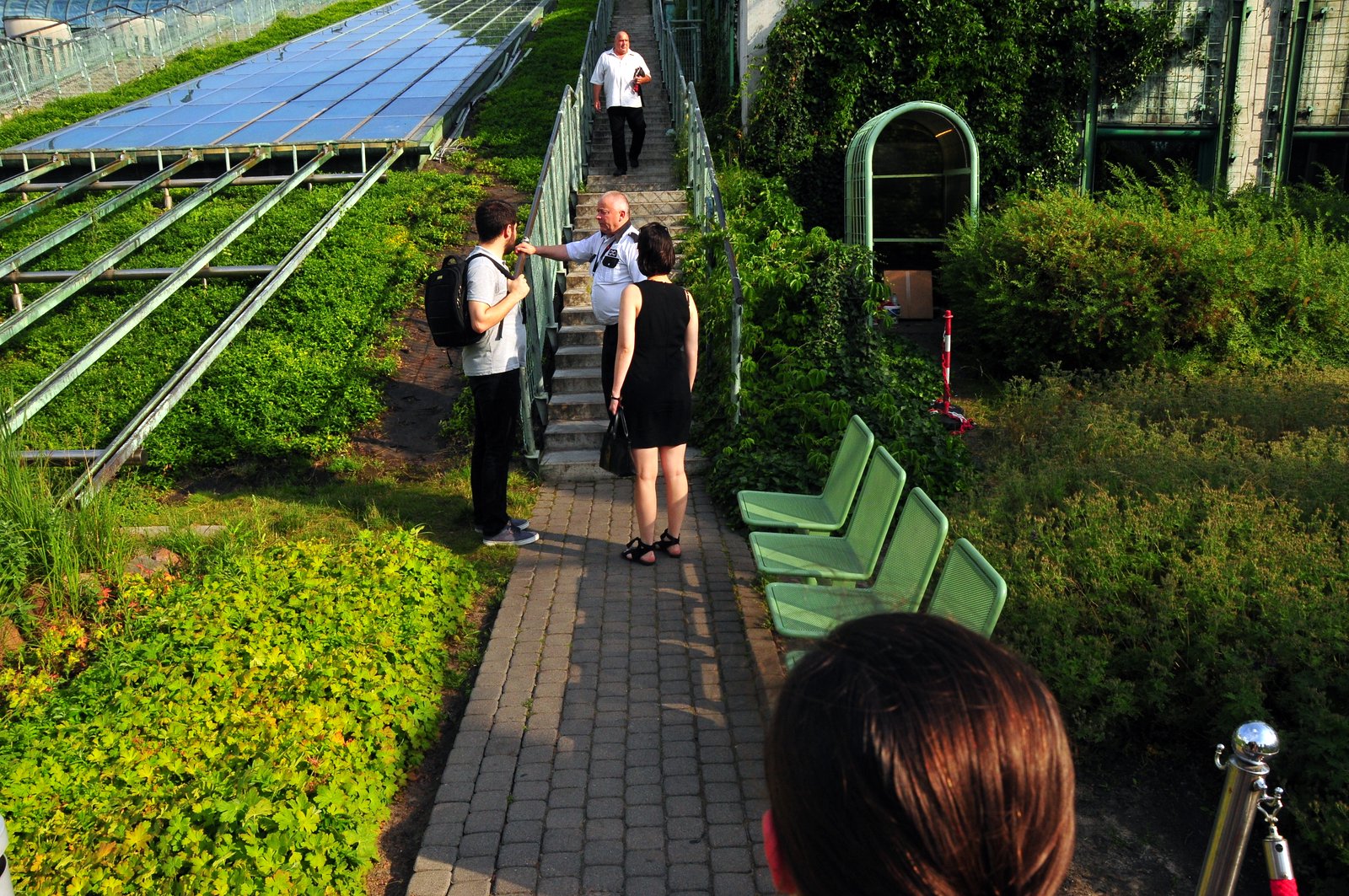

The second: we could go onto the rooftop garden.

“As far as I’m concerned, this is the best thing about ‘New Warsaw,'” K proclaimed. Some interesting ideas, for sure. The vines growing along the sides will eventually cover the whole structure, and I’m assuming this will serve to keep the hot sun out in the summer. Perhaps it will even have an effect in the winter. And it looks modern and fantastic (as in the adjectival form of “fantasy”) and all that, but I was honestly left just a little cold. Maybe that was a microclimate all the green produces…

Holy Cross Church

“Want to go see where Chopin’s heart was buried?” Not the most inviting notion for a five- and ten-year-old, but still, historic all the same.

Visiting churches in Poland used to be such a stressful experience for me. As a non-Catholic, I always felt like I should perhaps be there. I felt like I was intruding somehow. The fact that Polish churches are rarely if ever devoid of penitent worshipers in prayer regardless of whether or not there is a Mass being celebrated didn’t do much to ease the sense that I was barging into some place I had no business being.

Now, I go in and behave like I’d normally behave if I were going to Mass. I make the sign of the cross after dipping my fingers into the holy water fonts at the entrance. I find a quite spot and pray for a few moments. (With the Boy joining me, we whisper an “Our Father” together at some little side altar.) I feel like I belong. Mostly.

Ghetto Wall

If I hadn’t been really looking for it, if I hadn’t had my phone in my hand with Google Maps showing me theoretically where it was, and if I couldn’t read Polish, I wouldn’t have found it. I wandered around the block, looking here and there, following every little alley to its end.

It all started with a hunt for a beer. Not just any beer: Ciechan Pszeniczne Wędzone. Wheat beer made from wheat that had been smoke cured?! It sounded like heaven. The friend who recommended it told me where I could find it, which was quite near to our apartment, so after dinner, off I went. I found the location, but unfortunately, it wasn’t shop; it was a bar. I wasn’t really willing to go in and have a drink by myself — though in hindsight, why not? who says I had to enjoy it slowly, or even drink it all? — so I accepted my self-imposed fate and started back. Then I remembered: before we left the States, K and I had made a list of all the places we wanted to visit in Warsaw, and one of my additions was the Warsaw ghetto wall, or at least a marker. And I remembered looking at that map just a couple of evenings ago and realizing how close it was to our apartment. And I realized I was standing in that general area. So out came the phone and off I went.

At first, I thought this was it.

It was about the right height. It looked old, tired, worn.

“Surely,” I thought, “there would be some kind of sign, some kind of indication that this is the only remaining portion of the Warsaw ghetto wall.”

I kept looking. Between two blocks of apartments there was a courtyard. All the entries from one street were closed. “Perhaps from the other side.”

And then I finally found it. “Memorial Location” in Polish with an arrow leading down a dark corridor.

At the end, another sign. I went right first and found a wall higher than I ever imagined.

Bricks were missing, which had been taken to Holocaust museums in Melbourne, Houston, and most significantly, the Holocaust museum, Yad Vashem in Israel.

What as most striking was the fact that it still stands between to apartment blocks.

One could look out of one’s kitchen window (literally: one of the apartments was fully lit and I saw that these rooms are the kitchens) and see one of histories most brutal episodes. There were a couple of plaques, but nothing else. It was all so tucked away that you would have to be looking for it to find it.

The second segment of the way was a little more like I would have imagined it, except for the poorly translated yellow sign announcing “Night rest” from 22:00 to 10:00. Apparently, someone — or several someones — had visited the wall and raised a commotion late at night. Hard for me to imagine how that’s possible, but there it was: “Night rest.”

Final Thoughts

I came to Warsaw last week with certain expectations. I’d always been a Krakow fan myself. After all, everything there is old, not just rebuilt to look old. Warsaw was a city of gray, a city that was sad and perhaps tired. Maybe that was the Warsaw I first met in the mid-1990’s, but it’s certainly not the Warsaw of today.

For one thing, there are tourists now. There have been times as we walk down the street that I’ve heard everything but Polish from all the people we pass. The Italian restaurant just outside our apartment complex is always fluttering with Spanish, English, and other languages, and they seem to have a whole community of Indians to deliver food by bike via Uber EATS. When I first arrived in Poland in 1996, the sight of a non-white would send me in to paroxysms of excitement, and it was all I could do to keep from sprinting to them, hugging them, and declaring, “My God! Someone who doesn’t look like me!” (In the States, I think we tend to take diversity for granted.) Now, it’s no big deal.

Another difference: the metro. We have used it so much that I can’t imagine what we would have done without it. Well, we would have ridden busses and trams, but they’re such a pain to figure out, route- and scehdule-wise. A subway is simple: get on, wait, get off. When I first visited Warsaw, the subway was a newborn, with barely four or five stops. Now it’s a little toddler, with a full, long main line (a lovely blue line) and a second, growing, red, M2 line. Will it ever catch up to NYC, London, or Berlin? No way. But I don’t think that will keep it from trying.

A third difference: I don’t know that, other than Amsterdam and perhaps Berlin, I’ve seen a more bike-friendly city. Dedicated bike lanes everywhere (well, almost), and bike rental points all over the place.

Bottom line: if someone told me, “You have to move to Warsaw,” if someone held a gun to my head, I would not blink, I would not worry, and I’d grow to love this city as my own.

We will definitely be back.

Step Totals

Step totals (though not necessarily for the whole family) :

- Saturday 20,342

- Sunday 10,524

- Monday 25,304

- Tuesday 18,552

- Wednesday 22,799

We never tried to maximize steps, and we used the public transportation system quite a bit. All told, that’s just about 42 miles of walking according to FitBit.

W-Wa Day Four

We are a family of locomotives that are slowly running out of steam. Day four in Warsaw was like day three: one big thing, and then the rest — well, let’s just survive. Or so it seemed. It depends on how you define “event.” We’re not in Warsaw just to see the sights and tick this and that off our list. Above all, just like any good trip, we’re here for people. K has family and friends here that we’ve been keen on seeing; I have a friend here (sounds so lonely) I wanted to see and another friend from Warsaw whom I will see but not in Warsaw. (More on that in coming weeks.)

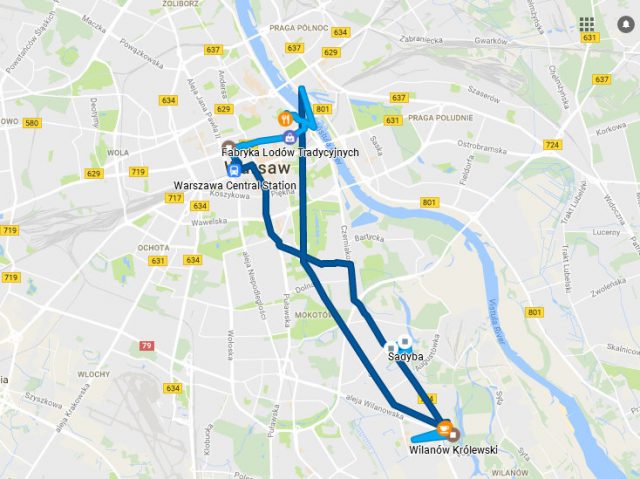

Today, we headed south, to Sadyba, where K’s uncle lives. Uncle M is out of the country with his wife, in Taiwan, so we meet with cousin N, who was such a little girl at our wedding and is now a college graduate, making her way through the world by teaching Chinese and helping run Uncle M’s record shop. We have coffee and cake, catch up on this, that, and the other, and then head back to the bus stop to head further south, to the Wilanow Palace. It wasn’t originally in our plans at all, but everything is closed on or all but Tuesday. The museum of Jewish history, closed. The Warsaw Uprising Museum — closed. The Kopernicus Science Center — no tickets available. So we head to another palace.

For the Boy, though, it’s all about the journey. He is in love with Warsaw because of all the different modes of transportation we’ve been using: subway, trams, buses, and in a way, his favorite: feet. He is a non-stop chatterbox as we walk along. “Daddy, there’s a bunch of cigarettes on the ground there.” “Daddy, there are three trams in a row!” “Daddy, there’s a man sleeping on that bench!” “Daddy, look at that tall building!” “Daddy, what are these bumps on the ground for?” I explain to him why, for example, there are raised “bumps” (as he calls them) along the subway platform. “It’s so that you know, even if you’re not looking, that you’re getting too close to the edge.” I explain it, and then a few minutes later, he heads to K to explain it to her. “Mommy, do you know why … ?”

Wilanow Palace is as you might expect any Baroque palace to be: huge, ornate, and overwhelming. You walk around this place that was only a summer residence to get away from the hustle and bustle of Warsaw (the city has since swallowed the village), and it’s hard to comprehend what types of worries the owners might have had. Such a different type of life, such a foreign way of thinking — at times, it’s almost as if you’re visiting a relic of some alien civilization that left long before you were born. You have dressing rooms that are bigger than your friends’ apartment in Warsaw, and it’s hard to connect to such people, almost impossible to feel any sympathy for the people.

After our visit, we stop for some ice cream (the second of the day), then head back toward the center of town to meet cousin N and cousin N — a different N; lots of N’s in the family — for a late lunch/early dinner. We end with a walk to the University of Warsaw Library, a building that is so unlike any other building in Warsaw that visitors just have to go see it for themselves. Except when the Minister of Education is visiting and the whole library, from top to bottom, inside and out, is closed.

It’s a little frustrating, but at least the Polish Minister of Education has some first-hand experience with public eduction, which cannot be said of our American equivalent.

And of course, there’s all the people watching to do…

Today’s Travels

W-wa Day Three: Palac Kultury

Kids can only go so fast for so long and then they break down. Yesterday, L broke down. Today, therefore, became an unplanned rest day. The Girls headed off to find a doctor to clear up a thing or two about L’s cough; the Boys headed back to the Old Town to wander about a bit.

We walked along the river before cutting back into the main Old Town area when we discovered this contraption.

“Is that the real engine, Daddy?”

We were able to see the changing of the guard.

“Are they practicing for war when there’s not even a war, Daddy?”

We got to see the monument to the victims of the Smolensk crash, which has evolved into the Polish equivalent of the grassy knoll among conspiracy-minded Poles.

We got to go into a church that had the the host on display for adoration without a soul in sight actually adoring it.

It was a nice morning for the Boys. The Girls? Well, probably better not to ask: looking for a doctor while on vacation can’t possibly be pleasant at all, even in a city like Warsaw.

Afternoon — lunch with a friend I haven’t seen in twenty years. He’s been in Poland since 1994, I think, and in Warsaw since 1996, I think. Give or take a year. He’s got his own company, a wife and two kids, a house — the American dream has come to Poland. But was it ever really just the American dream?

Late afternoon, we head to the Palace of Culture and Science, a gift from Stalin in the fifties. The story goes that Stalin offered Warsaw either the Palace or a subway. Varsovians chose the subway; Stalin gave them this.

That’s the story I’ve heard. I don’t think it’s true, but it’s a good story, and knowing the little bit I know about the Stalinist Soviet Union, it still has the ring of authenticity. What I do know is that it was begun at a time, in the early 1950’s, when most of Warsaw was still in ruins. It seems the height of arrogance to build such a colossus when the rest of Warsaw was in the state it was in, but Stalinism was never really about subtlety.

The views from the observation deck on the thirtieth floor are great. Varsovians have an old joke: the best place to view Warsaw is from the Palace, because that’s the only place you can’t see the Palace, but the truth it, it’s so centrally located that it just makes for great viewing whether or not it itself is visible.

And finally, I got to relive a scene from my favorite Polish movie of all time, Mis.

“A teraz, Pan ma relaks…”

W-wa Day Two: the Old Town

Sunday started like it always does: Mass. We decided to Mass at a church run by Dominican monks. But this time, we had to figure out, once again, how to get there. Google advised us to take the metro again, this time one stop further to the north, and then a 900-meter walk. As we made our way closer to the church, it became more and more evident that we were nearing the Old Town — Stare Miasto.

A family Mass, it was called, and indeed, there were a lot of families there. Throughout the entire Mass, some child or other was fussing, crying, protesting. We felt right at home.

Well, almost.

Before Mass began, K was talking quietly with the L about our plans for the day — we’ll go here, see that, meet with these people, those people — when the woman in front of us turned around and asked K to be quiet. Throughout the entire church, children were fussing, crying, protesting, and it was complete chaos for a church, and yet she turned around to hush us. As if that made any difference at all.

So easily am I side-tracked from what’s really important some time that that little gesture sat like a splinter in my mind for some time, distracting me from the Mass, distracting me from so much that was going on around me. I felt slighted, personally insulted. And I’m sure K thought nothing of it.

Indeed, when the Mass reached the point in the Liturgy of the Eucharist that everyone turns to each other and says “Pokoj z toba,” she turned right around as if nothing had happened, gave the biggest smile, and wished us all peace. And I immediately felt an idiot.

After Mass, we met up again with J, M, and E for a stroll through the Old Town, which is as much a paradox in Poland as anything else. In short, it isn’t old. It dates from the fifties at its oldest areas, and the royal palace was finished only in the seventies. The reason, of course, was simple: the Nazis destroyed everything. Hitler commanded his retreating armies to raze Warsaw, resulting in 80-90% of the city being destroyed. The Nazis made a concerted effort to eradicate all traces of Warsaw’s cultural heritage, essentially wiping Warsaw from history. According to one article, it was

one of the most ambitious projects in human history was initiated. No one had ever attempted to reconstruct the monuments of a war-torn city on such a scale. The decision to do so was also in blatant contrast with the prevailing conservation doctrine of the times. After the war, when faced with rebuilding a town which had been virtually erased from the face of the earth, Germany, the UK, Holland, France and Italy reconstructed only selected individual historical buildings. The reconstruction of Warsaw followed exactly the opposite tactic. (Source)

But like everything, political motivations joined with other catalysts and the project got under way. (Click on pictures for larger view.)

When you walk around that reconstructed area, then, it’s hard to feel anything but admiration for Poles. It speaks to a stubborn clinging to culture, to roots, to history, that has helped the Polish nation survive, literally. After all, Poland for a period literally disappeared from the map, gobbled up by greedy empires to the east and the west. That the country even existed for the Nazis to attack was something of a miracle, and it should have been a warning to Hitler that Poles would not just roll over and give up. The reconstructed Old Town bears more evidence of that.

As we were walking, I explained all that to the Boy and the Girl. L was fascinated and saddened; the Boy just asked questions about the technical aspects of it. How, for example, was the royal palace blown up and destroyed completely? Did bombs send it up into the air? Did it crash down and break? How can we be walking through it if it was destroyed?

We spent a good bit of time in the royal palace, which seemed to me at first to be a bad idea. I didn’t think the kids would particularly like it, but as I often am when it comes to my own children, I was surprised. L, the artist, enjoyed looking at some of the paintings, especially the huge historical paintings of Jan Matejko.

His Rejtan, which pictured the First Partition of Poland, captured both our attention and seemed a good example of what’s possible for the Girl’s artistic creativity: Matejko, it seemed, wasn’t a stickler for historical accuracy, placing people in Rejtan that weren’t even in the area, let alone in the room, at the time. So pink unicorns with green spots and blue stripes are not really all that significant when it comes to lacking in “realism,” whatever that might be in art. (That’s not to say that the Girl paints pink unicorns with green spots and blue stripes. She’s more likely to paint Apollo these days. Still, she might, on a whim, put pink Speedos on him.)

Then there’s Matejko’s attention to detail. He researched his subjects meticulously. When he got a chance, he examined cloth from the era of the painting, and when it was available, armor from the time of the painting’s subjects.

By this time, though, both the kids (as well as J’s and M’s son E) were getting a bit tired. There’s only so much of “look but don’t you dare touch” that a five-year-old and a seven-year-old can hear. There’s only so many ridiculously ornate rooms (by our standards) one can look at before one gets a little overwhelmed by it all. So we walked to the banks of the Vistula, took a walk, and eventually made our way to a ferry crossing.

Along the way, a few sights completely unknown to Americans, like a group of priests and seminarians walking along in cassocks, sun glasses, and baseball caps.

Or men wearing the same sort of minimalistic swim trunks that I wore as a competitive swimmer twenty-five years or so ago — Speedos we called the no matter the manufacturer, and I always wore baggy shorts over top of them until the very last moment before the race. And here, they’re the standard swim suit.

Once we crossed the river, we met up with M’s brother, B, and head to M’s and B’s family home, where K and I were visiting many years ago when Leszek Miller, then-prime minister, signed the documents that made Poland a part of the European Union. Such lofty ideas were nowhere to be seen during this visit, though. It was all about the usual: family, life here versus life in the States, and the like. “Tell us, hour by hour, what does a typical day look for you guys in the States?” B asked at one point in the evening.

In the end, to no one’s surprise, we found very few significant differences. The cost of health care might be the only difference: we pay much more than they do. But that’s a different, more political conversation…

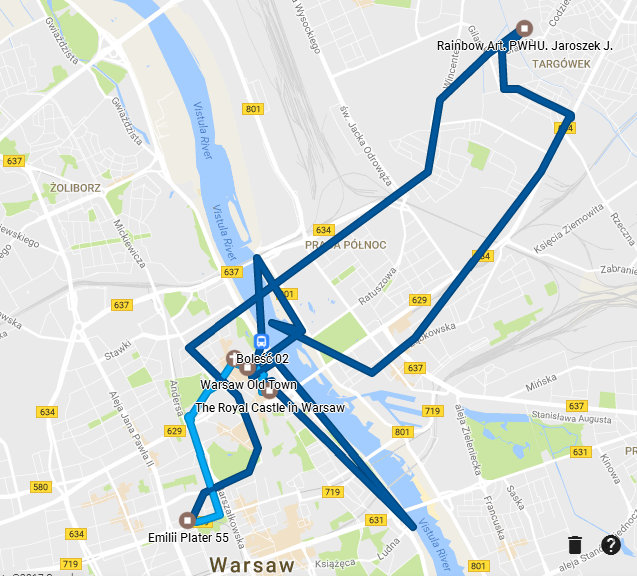

Today’s Travels

Not entirely accurate because Google is not entirely accurate, but generally speaking. (Of course we spent no time at “Rainbow Art, PWHU,” but that was the closest Google could find, and naturally I wouldn’t publish the actual address on the internet…)

More pictures at Flickr.

W-wa Day One

Where do you start when you get back from a day of wandering about Warsaw and you have almost 400 pictures that you manage only to whittle down to 78? At the beginning.

We’re all tired from our intense pace these first few days, and it showed when we all collapsed into bed: it was eleven by the time we headed out the next morning. I’d already been out quickly for baked goods for breakfast. A friend who’d visited last night told us she’d passed a promising looking bakery on her way here, so I retraced her steps looking for it. I knew she’d taken the metro to get here, and the nearest station is Rondo ONZ, so I walked along Świętokrzyska Street toward the metro stop, but I saw nothing but old-style shops, all closed for renovation. I kind of wished at least one of them was still open. Still, even with everything closed, it looks like the Warsaw I knew in the late 1990’s.

I couldn’t find the bakery A had mentioned, but I knew that if I just wandered around a bit in a systematic way, I’d find one. And sure enough, half a block later, there was Piekarnia Aromat. This was no typical Polish bakery: not a regular drozdzowka or rose-filled donut to be found. Instead there were things like raspberry brioche and something called “buleczka z pistacjami.” Literally, “a roll with pistachios,” it was a big hit with everyone — but L, of course. She was happy with her chocolate filled something-or-other.

Our plan for today was simple. In fact, we only had one thing on the agenda: Łazienki Park. It was a cool, overcast day — perfect for a long walk in the park. In the end, we spent about five hours there, and we could have all easily spent more.

First, though, we had to get there. We walked down along the edge of Park Świętokrzyski on our way to the Świętokrzyska metro station. The Boy was already counting the modes of new transport he’d experienced: “First a train, now the subway!” He thought for a moment and asked about trams.

“Later. Maybe even today.”

“Yesss!” (At one point the other day, when encouraged to “mow po polsku” he explained that “taaaaaak!” just doesn’t express happiness like “Yesssss!”).

A few stops later, we got off at Politechnika station, walked a few hundred meters (which included a surprise: a rescue vehicle roared out of the station right as we approached),

and there we were, in the famed Łazienki Park by the statue of Józef Piłsudski. The Boy insisted on a picture.

We wandered around a bit and took a gondola ride. The Boy managed to chalk up another mode of transportation, and the gondolier provided a bit of history, including the sad fact that the peacocks and other animals are harassed almost incessantly. “People will be people,” he concluded rather stoically.

As we were disembarking from the gondola, we met M and her son E, and with our life-long Varsovian as a guide, we continued through the park, eventually making it to the Old Orangery, which is filled with statuary and busts of the most eclectic collection: busts of various Roman emperors — including Caligula — fill the garden, while the interior itself is filled with busts for famous Poles in history, most of them completed by Italians.

As we were leaving, we came upon a group of young people, probably ages eleven to fifteen, who were starting some kind of drawing exercise. The lady running it asked L her name, jotted it down on a name tag with the comment that she was the third L in the group, and gave her some charcoal pencils. (“See, I told you,” laughed M later. “‘L’ has become a very popular name in Warsaw.”)

It turned out that it was a two-hour program. L begged to stay. She didn’t have to beg long. K and I were both thrilled that she had taken the initiative to participate in something like this. We explained that we wouldn’t stick around, that we’d leave her there and explore the park further on our own.

“That’s fine.”

“And you haven’t eaten since breakfast. You won’t be able to each for two hours more at least.”

“That’s fine.”

Our girl is growing up.

We left her among the statuary and went in search of gofry and ice cream. And people watching.

Łazienki Park is perhaps the best place in Warsaw to people-watch. There is an incredible mix of people: tourists, locals from two to one hundred and two, families, lovers.

We returned to a happy girl with two gofry to snack on as we made our way to M’s apartment, where her husband J was cooking dinner for us. Along the way, the big D300 put away, I snapped pictures with the little X100, trying to capture a few images that show the old Warsaw and the new, sometimes separately, sometimes juxtaposed.

There was the drug store that looked just like shops did when I arrived first in 1996.

There was an enclosed soccer field that seemed timeless, as if it had always been there.

There was a middle school with graffiti and rebar.

A newstand (“This, this, this is a newstand! I have meat here!” came to mind, a line from my favorite Polish film. In Mis, though, the newstand is not in a kiosk but its own building.) across from a used clothing store that sells clothes by weight.

And lots of people just going about their business.

Dinner and the evening flew by as it does with friends you haven’t seen in years. The conversation ranged far and wide, and for once there were no worries about whose toes we might step on with this or that comment when things turned to more political matters. We don’t see eye-to-eye on everything, and we can talk about it rationally and leave disagreements be. Not that that happened this evening. Parenting and parenthood tended to dominate the conversation and the environment in general.

After dinner, one last adventure: a neighborhood concert just a few blocks away in Szare Domy, a neighborhood of blocks of flats dating from the twenties that have small garden areas tucked in between the blocks. Usually closed off to non-residents, the neighborhood was throwing something like a block party, and everyone was invited.

The kids played. The adults chatted. The residents who stayed at home watched from the balcony.

Finally, around nine, everyone called it an evening. The Ds went back to their apartment after walking us to the nearest tram stop.

We made it back to Emilii Platter Street without worries, did some shopping, and had a final, amusing encounter. Walking out of the shop, E asked K, “Mommy, can I have the banana now?”

“No, just wait till we get back to the apartment,” she replied in Polish.

A young man sitting on a bench called out after us in English: “Why does he speak English when she speaks Polish?”

I turned around and summed it up as quickly as I could: “American reality.”

To Warsaw

To Krakow

Just as you’re stepping into the mini-bus, there’s always a little panic, a little worry, a question that just sits there for just long enough to color even the brightest day with just a bit of gray: will there be an open seat? Not having an open seat doesn’t mean that the driver won’t stop; it simply means he’ll stop and yell out the window, “Standing places only.” He’ll pack them in until there’s no standing room either, and we’ll have twenty-seven or more people packed into a bus with nineteen seats. As we rode from Jablonka to Krakow on just such a mini-bus, I saw that anxiety on each and every passenger’s face: the quick scanning of the seats, the relief when there was an open spot, the bit of frustration when there wasn’t.

Traveling the road to Krakow standing up is a challenge, with all the twists and turns as the bus goes through the low hills in the south of Poland that lead to the Tatra Mountains on the Slovak border. The side-to-side swaying is accompanied by a forward-backward challenge every time the driver pulls over to pick up and pack in a new passenger. With the number of noses simultaneously exhaling and the exertion of keeping your balance, the trip is an exhausting journey.

By the time we got to Krakow, the amount of heat and humidity made the whole experience almost unbearable. It was not the best way to start the trip Warsaw, but it was a reminder of the little gray linings of life in Poland, the things that drove me to distraction when I lived here.

In Krakow

First things first: find a bathroom. It was then that an unconscious but lingering question was answered:

Bathrooms in public places are still pay-only. The technology has changed: instead of a woman sitting in a little room that straddles the men’s and women’s room with a little basket collecting money, there is now a turnstile complete with a credit card reader beside a machine for making change from large bills. The cost: 2.50 zloty. That’s just about 70 cents. For a family of four…

Of course when E and I went in, I picked him up and carried him through the turnstile as I went through.

That done, we had some lunch and wandered around the Old Town for just a few minutes.

To Warsaw

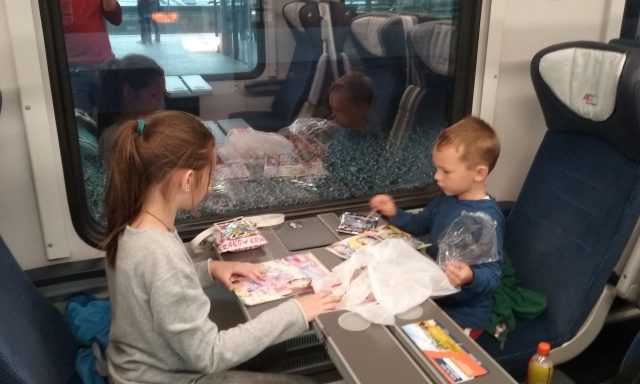

It was the Boy’s first train ride. The excitement was palpable.

Trains in Poland have certainly changed in the fifteen years since I’ve really traveled by train. We saw a few of the old trains we were used to, but they were all on railway sidings, out of commission. That’s probably good: those trains were not very comfortable. Still, it’s one of the things that differentiated Poland from Western Europe which have disappeared.

In Warsaw

“You won’t recognize Warsaw.” We’ve heard that from a number of people, and I don’t really think K and I understand the extent of the changes in the city that neither of us has visited in at least fifteen years. Still, looking out the window of the apartment we rented through AirBnB, I see that not everything has changed.

That building in the foreground, with the tired windows and dirty plaster, with the bars on the window that are in fact made out of concrete rebar welded together — that building is pure Communist-era Poland.

Boze Cialo

The terrace was all abuzz. The two grandmothers were chatting about details of the procession through the village earlier in the day. Grandpa was chatting with me about women and shopping. And a little blond angel was crying hysterically because of an unseen fall. Within all of this came the question: “Where are E and M?” We hadn’t seen them in some time and hadn’t heard them for a bit longer. Yet no one was worried. No panic. No flood of adults heading off in every direction, calling their names. “They’ll show up soon enough,” said grandpa, and within ten or fifteen minutes, there they were.

Village life. No worries about the kids when they disappear. No fears about the strangers among us because there are none. A certain kind of innocence that brings out both the good and the bad in people.

We spent the day in Pyzowka, a small village spread along the ridges of several hills just oustide of Nowy Targ, the nearest Polish town of any significance to Jablonka. Pyzowka is always a recurring destination, not only because of its beauty but also because of who lives there: D has been K’s best friend since childhood, the closest thing to a sister K has ever had. She is the Girl’s godmother and now, by proxy, a good friend of mine along with her husband, G. We always end up there a time or three while visiting the Old Country for the girls to catch up on gossip and that magic of just being in the same room together again. This year, though, because of various complications, today was the one and only day they could meet, so we went to Pyzowka for Corpus Christi.

Shortly after I first arrived in Poland in 1996, I encountered Corpus Christi for the first time. I had no idea what I was viewing. I prided myself on the depth of my understanding of Christianity that was in reality not even as deep as a small puddle of water. I had rejected it all because I knew better. Typical youthful arrogance, I suppose. Yet the first time I witnessed Corpus Christi, I began to understand that I didn’t understand.

Unknown Corpus Christi

Twenty-one years later and I’m a participant in the Mass on this holy day, a participant in the procession. I snap pictures as discretely as possible because I’m starting to understand the significance of the day, of the procession. Do I believe it all? That’s hard to say. Where do questions leave off and doubt begin? Perhaps it doesn’t matter in the end: I’ve come to see a certain beauty in the communal nature of Catholicism that makes me think that even if again I lost all my faith (the little strands I hold on to), I would still participate because of the value I see in simple act of people coming together and humbly submitting themselves to something bigger than they are. Such humility is rare these days, it seems.

Today’s celebration, though, highlighted the flavor a Polish village imparts on Corpus Christi. The procession began at the church and wound its way through much of the village.

At least twice cars approached, saw the whole road blocked with the procession of about 500 or so people, and turned around. I can’t imagine something like that happening in America or even a larger city in Poland. Life goes on despite holy days and celebrations, and in America of course, the vast majority of the population begin non-Catholics have varying opinions of Catholicism that color how they would view such a procession, mostly affecting the negativity of the hue, truth be told. At least in the South, where we live. That’s why the processions in America tend to be just around the church itself, not out into public itself.

After the procession, we had lunch at D’s before heading to the other side of the village to visit D’s parents, who are those rare Poles who packed up and moved from one village to another, almost as if they were Americans. Most Poles build a house and stay there. Stay there. But after several years of serving Jablonka’s animals as a veterinarian, D’s father and mother moved back to the village they grew up in.

While there, cousins and their families arrived, and we all sat around and ate and drank and chatted. It was then, at the close of day, that I really saw the magic of a Polish village. It’s only magical if you have connections, if you have someone who grounds you there. That almost seems axiomatic, but it shows why nothing like Polish village life exists in mobile America. Packing up and moving across the city, across the state, or even across the country is no big deal. Put your house on the market, find a new place, and arrange for movers. It’s as simple as that. But it’s far from simple when you really look at it. Roots can’t grow when you’re constantly transplanting.

Wednesday in the Village

Polish Village Reality

After a quick breakfast, a little reminder of Polish reality, at least an older reality: no hot water in the morning in the summer. The energy for heating the water is not electricity, for that would be far too expensive, but rather it comes from coal, as in a small coal-burning furnace. Babcia makes a fire in the evening to have warm water for baths, but by the morning, it’s cooled down.

So to wash dishes, one has to warm water in a pot and then poured into the sink.

Homes built in the last fifteen years or so have different systems which means less work for the hot water. Apartment blocks in the city have central heating for hot water, as do whole neighborhoods in some sections. But in the village it was always (and is still at Babcia’s) simple: to take a bath, build a fire.

Jarmark

“Fish monger” is about the only use of “monger” I know in English. There must have been others, because the word exists, but it’s largely fallen out of common use, but that’s too bad: it would really come in handy when describing the flea market that appears every Wednesday in Jablonka. There are sock mongers, cheese mongers, suit mongers, hat mongers, jacket mongers, shoe mongers, farm tool mongers, auto part mongers, garden tool mongers, and just about anything else one could imagine.

Each of those mongers have a script, it seems, when it comes to selling. They begin always with “Prosze bardzo,” which would really be translated “I really ask” but in essence “very please,” which itself is a rather literal translation. It’s not literally “Can I help you?” because that would be “Czym moge pomoc?” Yet it’s a common greeting in stores. Next step: make a million suggestions about how this or that product is in fact perfect, is in fact just what the customer has been looking for. If the customer protests, well there’s always this over here, which would be perfect.

At some point, the monger will try to show how amazing his product is. When I bought a Russian-made Zenit camera in the market in Nowy Targ some twenty years ago, the monger literally drove a nail with the base of the camera to show how tough it was. Today, a jacket monger poured mineral water water on the jacket K was trying on to show how effectively water proof it was.

If the monger finally realizes that there’s nothing to do but admit defeat, the responses become almost cold. “Nie ma.” Finally, if a customer finds something she likes but wants to look further, the whole exchange ends as it began: “Prosze bardzo.”

We came to Poland without jackets with the plan of simply buying them today at the market, so we met that formula several times today. Though I’ve been to that market (and others in the area) countless times and went at least once a month when I lived here, I only now noticed that linguistic pattern.

Respect

Poles take care of their graves. They wash the grave stone, pull weeds from around the grave, keep candles lit on the grave almost all the time.

Today, Babcia asked us to take care of Dziadek’s grave, sending us out on the one-mile walk to the cemetery with various cleaning clothes and several new candles. The walk revealed a new reality for Jablonka: there is now so much traffic through the main road of the village which leads from Krakow to Slovakia and eventually Budapest that the Boy was virtually yelling to tell us all the wonderful things he was noticing.

But some things don’t change. The two main pavilions that hold everything from money changers to butcher shops, from a law office to a toy shop, from a hair salon to a post office, from a surveyor’s office to a newsagent — they still stand as they have since I first arrived in 1996.

We cleaned the grave, lit new candles, pulled some weeds. We prayed an Our Father and threw away the old candles before moving to the other family graves.

“This is your great-grandmother and great-grandfather,” K explained, in Polish.

“What does that mean?” asked E.

K explained in Polish, then added a few key words in English. It’s a fairly typical way she talks to the Boy. Yet he’s already begun chatting in Polish, so by the time we leave in six weeks, it should be a whole different story.

Old and New

Within a village as old as Jablonka, one can find the newest of the new and houses that have stood for well over a century, and just about everything in between. This house stands on the way from the church and was built in the early 1920s. The plaster has fallen off in several places, yet it’s still occupied. It’s positively romantic.

Just down the street is an older house, now unoccupied. The door was open and we peeked in. L couldn’t understand why no one lived there. I can’t either.

Shops

Traditional Polish shops have one thing in common: they are crammed full of goods. It’s as if every square meter is the only square meter of the shop.

Newer stores are not like that, but shops in the pavilion (see above) are all packed tight, like herring in a jar to translate from Polish.

Evening Walk

When it’s this gorgeous outside, what else is there to do but take a walk?

Loans

Homes used to be built and paid for at the same time. It explains why there were so many half-finished yet occupied houses in the area when I first moved here. Loans were hard to come by. Now I see television advertisements for loans to pay for vacation. Not sure that’s necessarily a good change.

Arrival 2017

When I first arrived in Poland, everything looked so very different. It wasn’t just that it was a different country. I was living in a very rural area for the first time as well, so everything in 1996 looked doubly new.

Subsequent arrivals had a feeling of comfortable familiarity, and that’s a pleasant enough feeling, but it can take a bit of the edge off the excitement of arriving. Just a bit.

Four years ago, I got a flash of that newness again when L and I spent the summer here. She was six, and everything was new to her. It was her third time in Poland, but the first time as a six-year-old, and there’s an enormous difference between a four-year-old and a six-year-old.

This time around, it’s the Boy’s turn: he’s been so excited about coming to Poland for the last few weeks that it’s been a common topic in our conversation.

“Daddy, are you looking forward to going to Poland?”

Monday he was terribly excited and then terribly confused when we told him, once again, that we’d be leaving today but arriving tomorrow.

When we finally made it to Babcia’s house, the excitement was somewhat tempered by the exhaustion, but a lunch of clear broth with homemade noodles followed by a cutlet with new potatoes and fresh cabbage generously garnished with fresh dill was refreshing enough that after dinner, we decided to head out to look for cows. The Boy expressed the thought in Polish and, as he always does, had significant trouble with the trilled “r” in “krowa,” so we went out in search of klowa.

There were none still out by the time we made it to the fields, but there were still farmers out working in the fields, turning and gathering hay.

He examined a bit of the freshly cut grass,

and somewhat drier grass — not quite hay but close.

And though he was cold throughout the whole walk, he said nothing. “I was having fun,” he explained, “and I didn’t want to go home.”

A good start to the trip.