Twenty Years Ago or More

It always amused me how much stuff the average Polish woman (and it’s always the woman) irons. “Do you all iron even the underwear?” I once quipped.

There is a certain sense behind it, I guess, if you worry about wrinkles in everything. When I first lived there, I didn’t. And I didn’t even have an iron if I wanted to smooth out my clothes. “We always laughed about how obvious it was you were a bachelor” one of my former students once confessed.

Ironing sheets, though? Yep.

“I have a film you must see.” We were sitting in a restaurant, waiting for the next bus back to Lipnica, when Janusz told me this. “It’s a perfect film.”

“What’s it about?” I probed.

“Poland. It’s about — you just have to see it,” came the response.

For the next few weeks, whenever we met up, Janusz brought up the film.

“When are you going to come see it?” he would ask. “You have to see it. It’s a perfect film.”

Little did I know: classic and perfect.

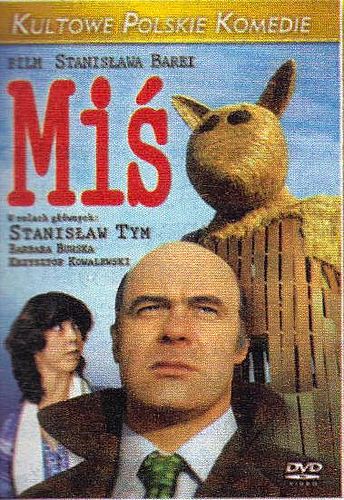

The first time I saw the Polish cult comedy Miś (“Teddy Bear”), I knew I’d have to see it again. I’d laughed so hard at some scenes that it was difficult to catch my breath, but I knew I’d only caught part of it. This was partially because of language — my Polish, after all, isn’t perfect — and partially because of the layers of the film.

In the years since I first watched the film, I’ve seen it countless times. Those layers are still revealing themselves with each viewing: little touches like signs in the background and repeating musical themes, things you’ll never get from one viewing. Indeed, I’ve watched it so many times now I can quote whole sections of it, and no matter one’s situation, there’s almost always a quote from Miś that is perfectly applicable.

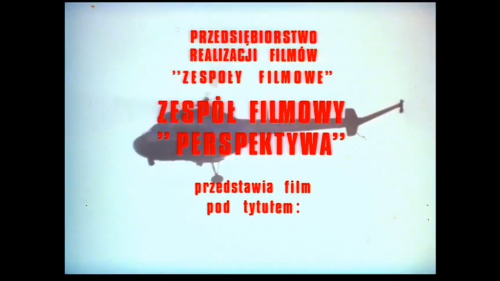

The first shot is of a helicopter, clearly working as a flying crane. We see the wire, but it takes a moment before we see what is hanging from it.

On the ground, it becomes immediately obvious: it is a fake building with police officers milling around, part of a suprise speed trap.

As the credits roll, other officers put up two-dimensional fake buildings to create a small “village” near the road. The reasoning is simple: Polish traffic law requires drivers to slow in a teren zabudowany.

Both words have as close a thing as a cognate as just about any words in Polish: “teren” means “terrain” and “zabudowany” derives from “budowac,” which means “build.” So teren zabudowany literally means “terrain built.”

The trap, though, is incomplete without people. Other officers soon appear with variously dressed mannequins in hand. An off-screen ranking officer’s voice instructs, “Put them in a line,” and after a pause, we hear an explanation: “There must be some sign of life.”

The opening scene concludes with a soon-to-be-critical officer announcing over the radio that they are ready and that “moze zaczynac!”

“We can begin!”

What is amazing about the film, made in the very early 1980’s, is how much it mocks the Polish Communist reality and the effects of a state monopoly on everything from goods to ideas. That it made it past the censors is a minor miracle: I’ve really no idea how it could happen other than the notion that perhaps the Polish Communist party was more forgiving than Big Brother to the east. All the same, such blatant mockery?

The story, though, is simple: Ryszard Ochódzki, the director of a sports club, is trying to beat his ex-wife to London, where they have money under a joint account. Each knows the other will drain the account, and so it’s a mad race to see who can get there first. When Ochódzki’s wife, Irena, tears some pages out of his passport making it impossible for him to travel abroad, he devises one of the most complicated and convoluted schemes to get to the bank despite this seemingly insurmountable obstacle.

It’s a miraculous film, and many of the scenes resonate with my own experiences in Poland in the mid-1990’s.

“Are you going for the bride or the groom?” I was standing at the car rental counter making small talk with the young lady completing the paperwork for us to rent our car, and I answered without giving any thought to the oddness of my response.

“Neither. I’ve never met either of them.”

She smiled. “How did you get the invite if…”

I started pointing over my shoulder. “She knows the bride,” I explained, indicting behind me with my thumb my absent wife. I turned around to discover K wasn’t standing behind me.

“Wherever she is…” I continued.

I have, in fact, only been to one other wedding where I didn’t know the bride or the groom, and it was the evening I proposed to K in 2003.

There was little difference between that evening and Saturday’s wedding. During the 2003 wedding, K and I sat with a group of her college friends (it was a college friend’s wedding), but I really knew none of them.

Saturday, we sat with a group of folks who were from the same village as K (the father of the bride was from Jablonka) but otherwise strangers to us.

No matter: we were soon talking with them as if we’d known them for ages.

That’s part of the magic of a Polish wedding: you can go knowing no one and be fairly certain you’ll still have a great time. The copious amounts of alcohol certainly helps lessens everyone’s inhabitions, but there’s something more to it than that.

Polish cuisine, in my experience, is centered around soups. I’m not a culinary expert or anything of the kind, so this is undoubtedly my personal preference coming to the fore: what has always caught my eye (and my tastebuds) in Polish cooking has been the soups.

Barszcz z uszkami is a treat beyond treats: we only have it once a year because the uszki are so time-consuming. It’s one of E’s favorites.

Żurek is such an odd-ball dish for Americans: soup made from a base of fermented rye flour? How weird. And how utterly delicious. It’s one of L’s favorites.

Ogorkowa? Pickle soup? “Get out!” was my first reaction. Who the hell makes soup out of pickles?! It’s absolutely perfect.

K likes most Polish soups, but she probably agrees with L and E that a simple rosół is the best. Babcia always makes it for us as our first dish in Poland, and a gentle, easy broth like that is the perfect thing after traveling.

And then there are the other: koperkowa, chłodnik, kapuśniak — the classics. But there are a couple of soups that stand above them all for me: flaczki (not because I love it so much — I do, but it’s not a favorite — but because I only get it in Poland: K absolutely is not a fan) and my hands-down favorite, kwaśnica. Not so much a Polish soup as a regional highlander soup.

We usually stick to soups in the winter and give them a break in the summer: having the stove on that long really warms up the house, and we want lighter meals in the summer. Except for rosół and koperkowa (none of us is really a chłodnik fan), the soups disappear.

Until the Girl asks K to fix that one soup — you know, with the potatoes and bacon bits.

And so we had for dinner a soup I have always thought of as a winter soup.

“We should do kwaśnica,” I will say some time in October or November.

“No, it’s not cold enough yet,” comes the reply.

But all our Girl has to do is ask for kwaśnica, and it can be 90 degrees outside, and K will not hesitate.

Over the summer, posts from our 2017 trip to Warsaw appeared, as they do every year, in the timeline feature to the right. I read about looking for baked goods that first morning, and I remembered how very communist-era Świętokrzyska Street looked then, and I wondered if pictures of it were on Google Maps.

I felt like I was walking down the street in a scene from Miś. Those shop windows looked exactly like they did in the early eighties.

Two years later, it was all gone.

Two more years after that, an entirely new and modern building had taken its place.

More of the old Warsaw fades away.

Continuing down Świętokrzyska Street, one reaches ONZ Rondo. In the distance, building after building appears year after year.

Finally, there’s Prosta Street (“Straight Street”). Looking off in the distance, one could see only the ubiquitous Easter European apartment blocks.

Just a few years later, a typical Western city has sprung up in the distance.

The Warsaw I knew in the mid-90s is all but gone. Then I remember: that was thirty years ago. Of course it’s all disappearing.

Sometimes, you need to write, but not here. Not yet.

A picture from almost 30 years ago when I was exploring the area of southern Poland where I’d just moved…

I found a whole batch pictures from that period that I had forgotten I’d scanned.