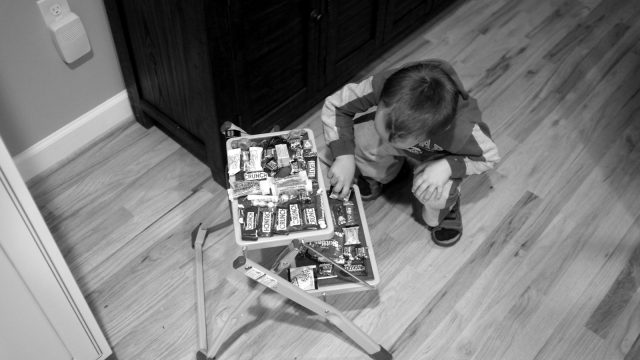

The Boy was playing CandyLand with K, and after he’d won the first game, he was eager to play another.

“I’m going to win again!” he proclaimed, and for a moment, it looked as if he were going to do just that. He shot ahead with double color after double color. Then K drew the gum drop and zoomed ahead.

“Oh, I’ll never win!” he proclaimed, frustrated.

“Yes, but you might draw another candy piece and move ahead, or Mama might draw the candy cane when you’re way past it and have to go back many, many spaces,” I reasoned. But as I often remind The Girl, there’s no reasoning with a four-year-old. He continued playing a bit halfheartedly. He drew a candy piece eventually, but K had shot so far ahead by then that his chances of winning really and truly were gone.

And with that loss, his desire to play was gone as well.

I remembered the whole time they played the new buzzword in education: grit. It’s really nothing more than perseverance in the face of difficulty and setback, but educators and researchers in education like new jargon. (I suspect it’s mainly from the latter.) And so “grit” is thrown around in education blogs and educator gatherings quite often these days. It was rewarding to see The Boy showing some of this perseverance. It took a good bit of encouragement, but he finished the game, learned the lesson (?), and we had a nice close to the afternoon.

The next night, The Boy and I are working with Legos. I was building a jail for him, and he was building a mystery. Not having a plan, he found the process a little slow-going and frustrating.

“I just can’t get it,” he fussed as he couldn’t get two pieces joined. He threw them down, and for just a moment, I thought the chances of a relaxing evening of Lego-ing were gone. But just for a moment. Seeing everything as a teaching opportunity — or at least trying to — I showed him how to get the pieces together, then pulled them apart and had him try again.

“I got it!”

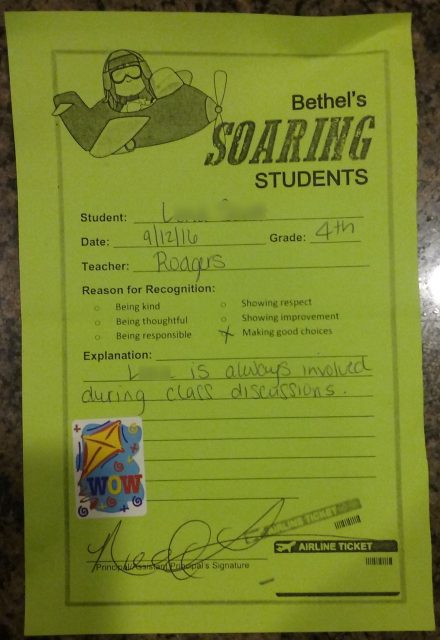

Two opportunities to teach that could have disappeared but didn’t. The trick for me, though, is to transfer that to my students. Everything can be a moment to teach, a learning opportunity, for the at-risk kids in my charge. They lack social skills, patience, anger management methods, volume control, grit (there it is again), a growth mindset (another edu-speak jargon term that’s hot now). Every teaching moment can’t bloom — I’d never get to the curriculum some days. The balance must be there, but there’s so much they need before they’re gone off to high school…

Inspired by the Daily Post’s prompt of the day: Gone.