Sometimes, there are no right decisions; there’s only a queue of increasingly wrong — sometimes increasingly harmful — decisions, all standing patiently in line for us to inspect them, reinspect them, obsess over them, fret over them, stress over them, reexamine once again, reconsider yet again, and constantly feel crushed by them.

Sometimes, there are no good decisions; there’s only a pile of increasingly worse decisions — often increasingly harmful — and we just have to look them over and decide which of these awful decisions we will take, which of these awful harms we will inflict.

It’s never something as morally abstract as the trolley problem. It’s always direct harm to a relationship we treasure. It’s always choosing one hurt to inflict over another to someone we don’t want to hurt at all. And so it always doubles back on us and causes us as much pain as we doled out. Perhaps more. Perhaps it’s only with a little experience and a few years that we see that.

Sometimes, there is no way to juggle all the things we’re required to keep flying overhead in never-ending arcs. Focused on keeping the chainsaw’s roaring blades away from our hands, we lose sight of one thing or another, and the knife comes clattering down to the floor, damaging something. Or worse, someone.

I feel like this teaching throughout the day: there are little decisions I have to make constantly (Do I let her go to the bathroom now or would it be better later? Do I let him go to the vending machine?) and some only seem little (Do I call him down now, knowing how he’ll react and knowing the disruption that will cause — which will be the bigger disruption? Do I correct her writing now, even though her mistake has only a tangential connection to the topic at hand? Do I try to force this kid to work with someone or let her work on her own again this time even though we’ve had the discussion about the merits of collaboration and made an agreement to try the next time we’re in groups?). But there is always — always, always — a decision just lurking.

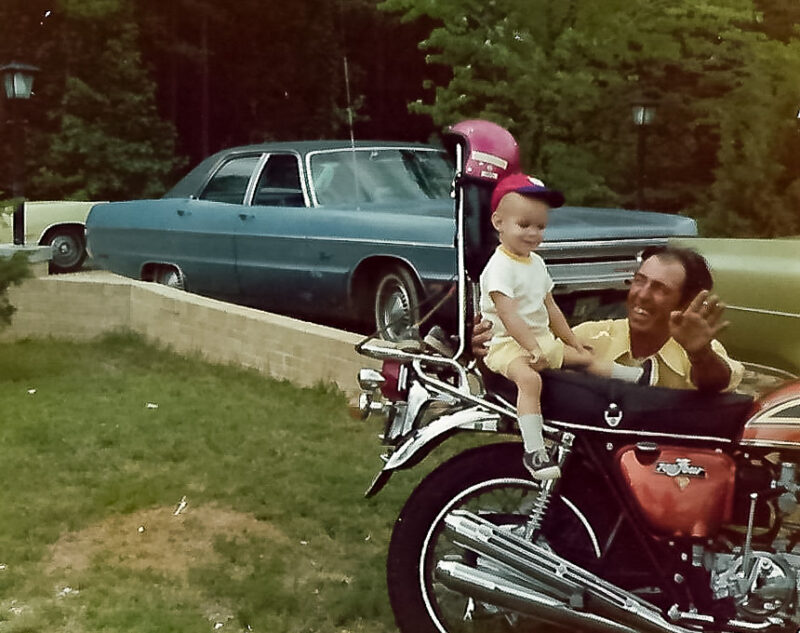

Nowhere else is this more true than in parenting. Things glide along fine until they don’t, and then someone is always going to be disappointed; someone is always going to be hurt.

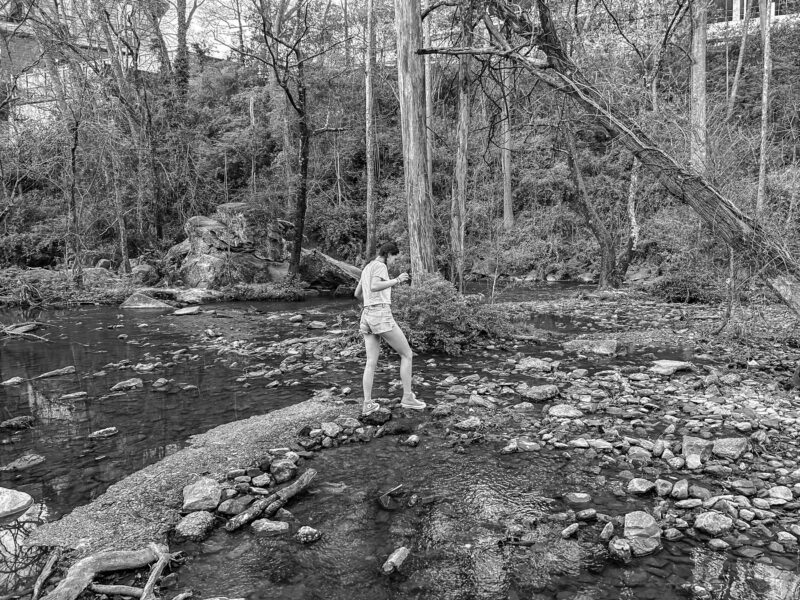

This is especially true, I’m discovering, as one’s child moves closer and closer to that magic number: eighteen. It’s especially true, I’m seeing, as one’s child becomes increasingly cognitively developed and is no longer making arguments like, “I just want to,” but sound, logical arguments that acknowledge their own shortcomings in the present situation and yet make a good case for getting what she wants. It’s especially true, I’m learning, when she fights back tears of frustration and tries her level best to keep her emotions in check and act like an adult.

“Because I said so” is no more a legitimate reason than “I just want to.” At least it’s not anymore, because the power of logic: what’s going to change in the next two and three-quarters months? Is she going to be any more cognitively developed? Emotionally developed?

K and I love being parents, truly we do, but even after nearly eighteen years of it, we’re still wondering if it will ever get any easier.