Papa’s existence when the meds that keep him calm and sedated changes from moment to moment: There are lucid moments when he is just like the Papa we all know and love, there are moments enveloped in hallucinations, and there are moments that seem to fall somewhere in between.

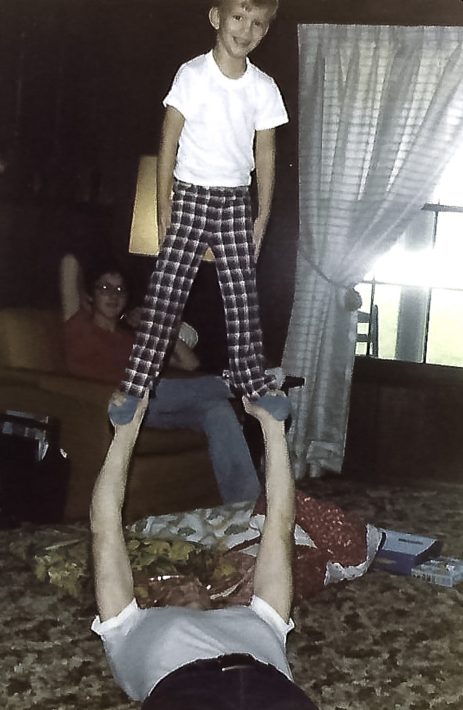

This is a lucid moment.

He occasionally smiles while hallucinating, and it’s such a mischievous little smile that I want to catch a photo of it. Tonight, he smiled that smile, a little kid’s smile when he’s gotten away with something and yet is still just nervous enough to realize that he might not have in fact gotten away with it. An “I know you know I did it, but please don’t tell on me” smile. I didn’t have a camera ready, though, so I went downstairs and got our good Nikon. I was telling Papa about that smile and how much I wanted to get a picture of that smile, so he smiled for me. It’s not the smile I’d initially wanted, but it was a smile of intent, a smile of purpose, a smile to fulfill a request. A smile that said, “I know I’m having a lot of problems following instructions when you ask me to open my mouth or to roll over. Right now, though, I can do exactly what you asked me to even if I’m not sure why you want me to. I trust you and will do it because I trust you.”

Those lucid moments are rare, and they are increasingly rare with each passing day. The hospice nurses all say that they have never seen anyone with Parkinson’s progress this quickly. Every day is literally a new normal. Yesterday it became clear that he could no longer eat solid food because he didn’t chew it. He kept it in his mouth sometimes, partially chewed it others, and every now and then chewed and swallowed, each motion of his jaw a supreme effort. Today we gave him only pureed food, and in the morning he did a good job with it, but in the evening, it was difficult to get him to open his mouth to eat. He no longer can draw liquid through a straw, and when he does get liquid in his mouth, he almost chokes on it, so we bought thickener and we spoon-feed him his thickened water to keep him hydrated. Today we also stopped giving him pills to swallow: they’re all ground up own, sprinkled on spoons of yogurt. What tomorrow will bring is a complete mystery.

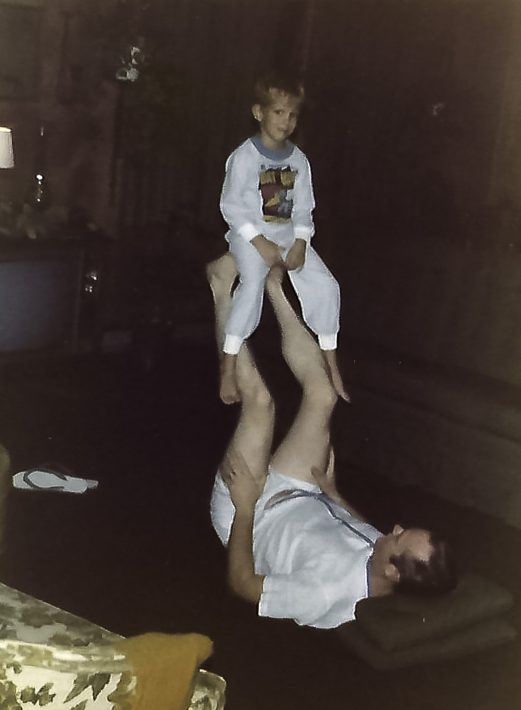

This is a hallucination.

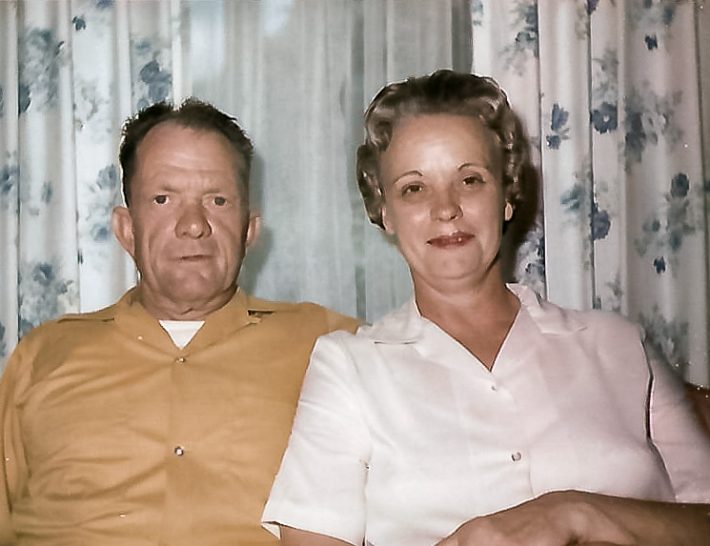

He pulls threads out of thin air. He talks to people who over his bed, who sneak behind his bed and hide, who stand on either side of his bed. Strangers come to visit him as well as friends. Nana comes often. “Hey, babe! Don’t you think it’s about time we get out of here?”

This is the picture I hesitate to put on here, but this is the reality he’s suffering now. This is the reality that leaves us shaking our heads wondering how much one poor man has to suffer. This is the reality that creates new habits: I walked out of the room today just as he started saying something. I paused for a moment, then realized he was talking to a hallucination. I didn’t respond. I just continued out.

These are the moments when he seems most vulnerable, too. The hallucinations don’t frighten him: he once said he saw a hangman standing by his bed with a noose, but other than that, the people who come to visit him seem relatively harmless. He’s restless, though: he’s always been a mannerly man, a gentleman, a problem solver, so he wants to respond to all the things he sees around him, deal with all the issues around him (the threads that hang endlessly over his bed, for instance). In the past (i.e., earlier this week), when he started talking to these hallucinations or pulling at the threads, we did as the nurses advised: we played along and asked the person he was talking to to leave or took that threads ourselves. “Don’t worry,” we’d then reassure him. “We asked him to leave. Did you hear? Did you see him leave? He just walked out the door.” Now, he doesn’t engage with us when we say those things. That change has come in the last 36 hours.

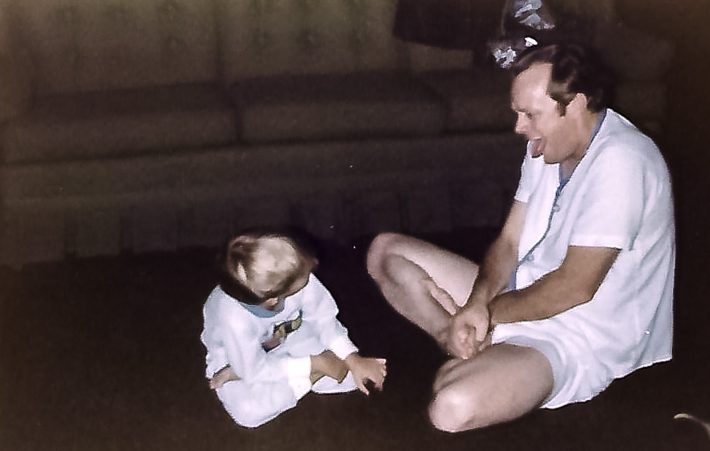

This is a mystery.

Not hallucinating, not engaging with us — just there. Remembering? We don’t know. This might disappear tomorrow because it only appeared a few days ago. The way things change, “normal” is a fluid concept that can change within one day.

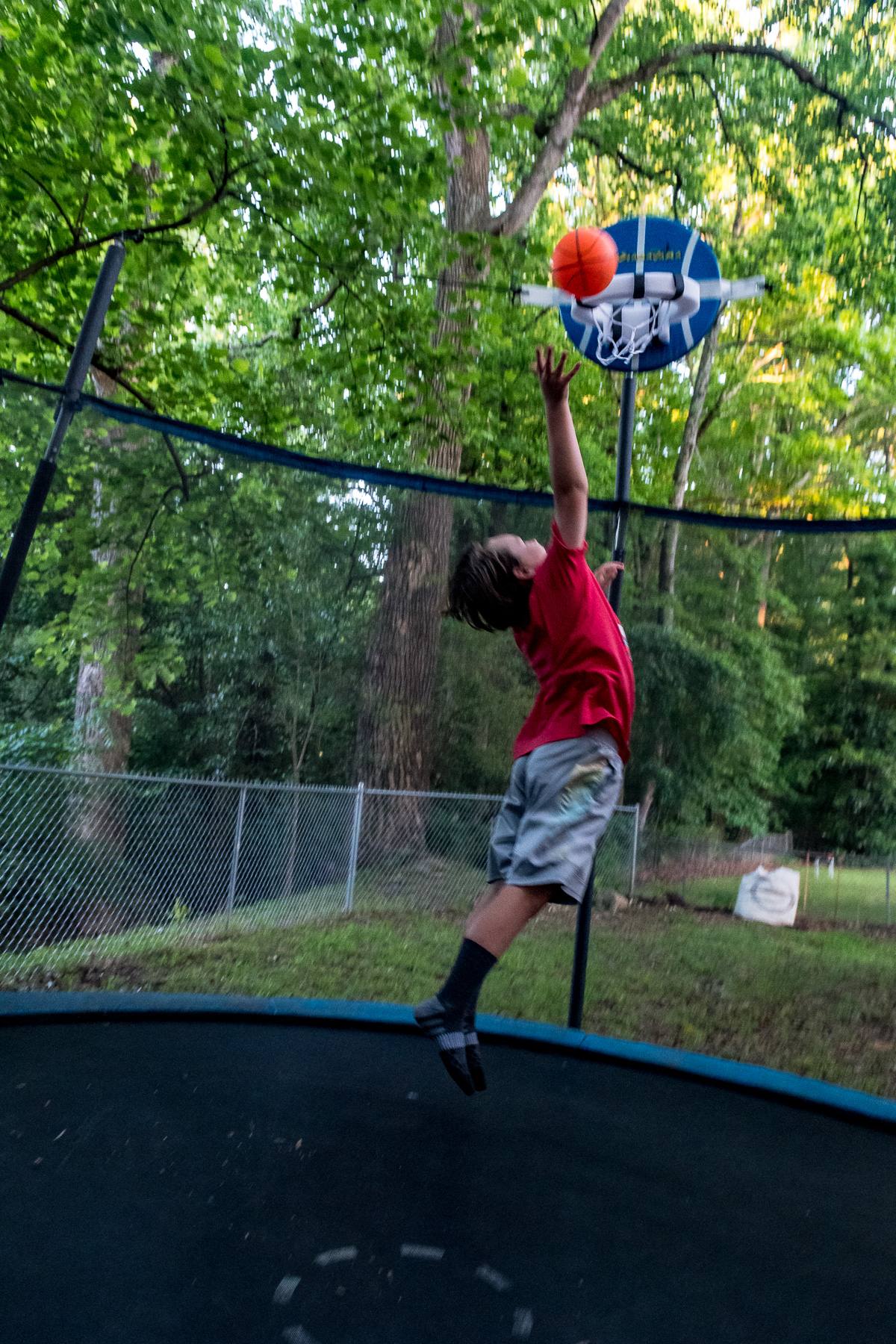

This is the only thing that seems to help these days.

This is what I feel guilty about neglecting with Nana: I didn’t realize how little time we had left with her once she came back from rehab. I didn’t realize how quickly she could go. I didn’t take the time simply to sit with her and to talk to her as much as I could have or should have. And now, so much that we say to Papa just goes unacknowledged. Perhaps because he didn’t hear. Perhaps because he didn’t understand. Perhaps because he was busy talking to someone else. But there’s one thing he understands.