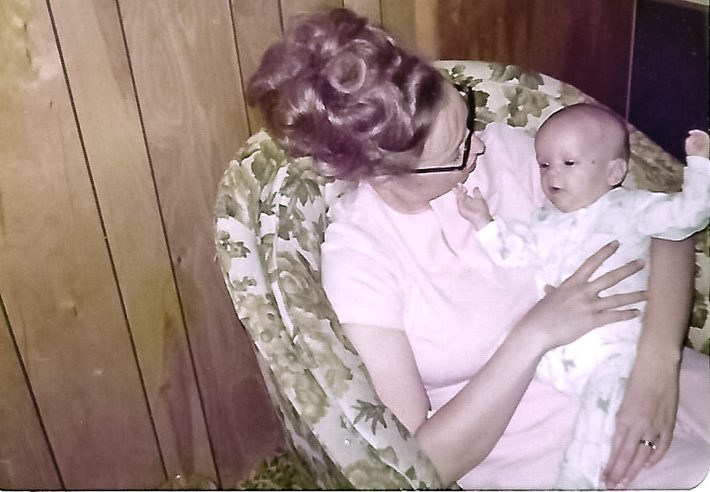

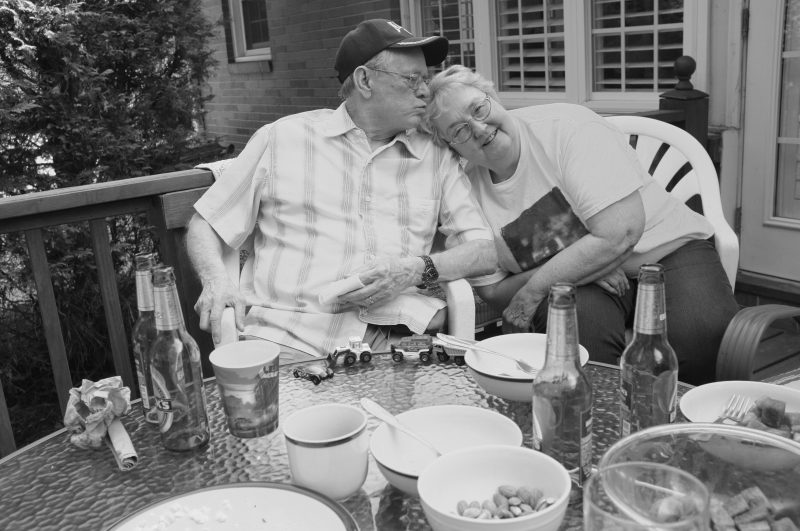

It’s been five years now since Nana passed. E is the same age now that L was then, and now L is only a few short months from being a legal adult.

A common theme in my writing is the suddenness and recurrence of my realization o f just how much time has passed since a certain event, and using that realization to project into the future with the realization that it will come just as quickly as this moment has arrived. Almost thirty years ago, for example, I left for Poland for the first time; project those same nearly-thirty years into the future, and I’m almost eighty, the age Papa died two years after Nana, now three years ago. See? I just did it again: created a loop of time.

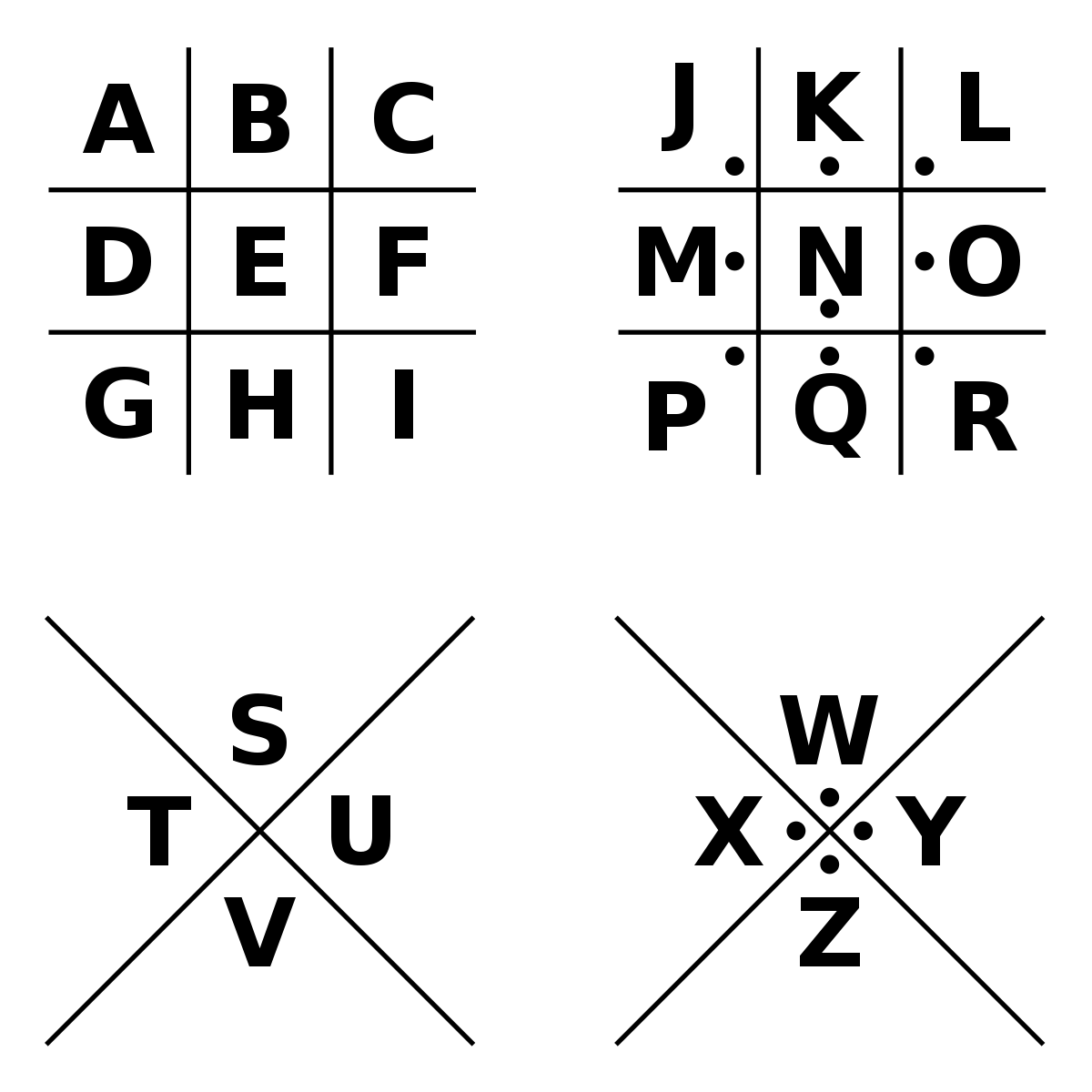

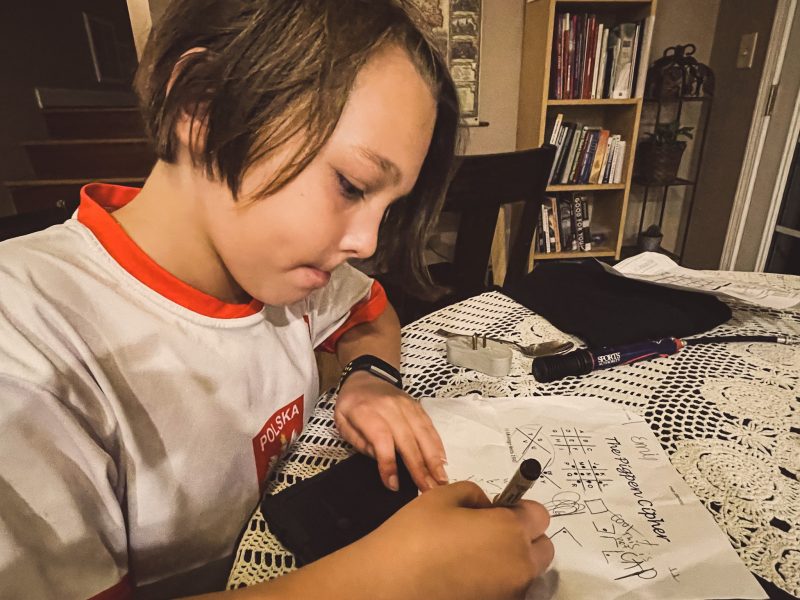

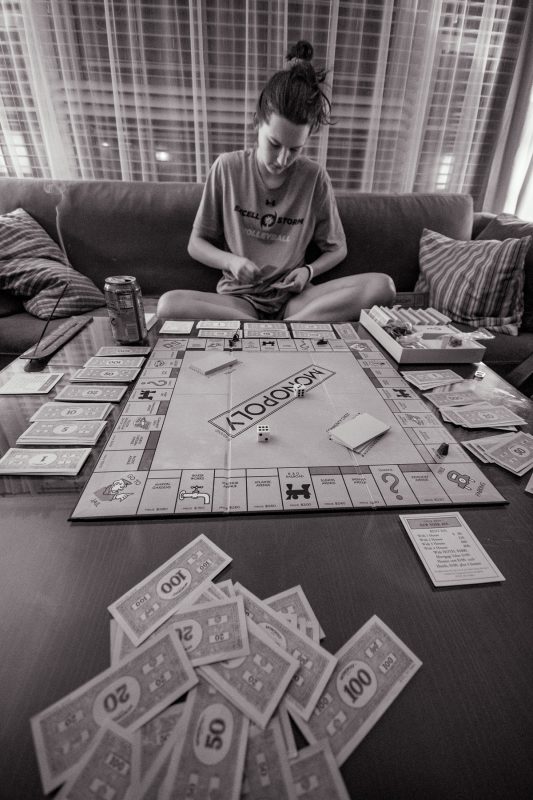

In those five years since Nana’s passing, the GIrl has grown almost an entire foot; the Boy has reached a point that we just barely have to look down while talking to him. In those dunce years since Nana’s passing, the Girl has become a volleyball star and broken then re-broken high school track and field records; the Boy has picked up guitar and trombone as well as becoming a confident soccer player.

In another five years, the Girl will be finishing up college, lining up graduate school (with her interests, she will likely end up getting a doctorate straight away), and firmly established in a life of her own, a life without (to some degree) K and me. In another five years, the Boy will be almost done with high school, thinking about college, and probably still playing trombone and Fortnite. I’ll be creeping ever-nearer my sixties; K will be in her fifties.

With all this in my head, we go to Polish mass in the afternoon, and while everyone is getting the pot luck afterward read, the Boy heads out to the playground and it’s clear how much he’s changed…