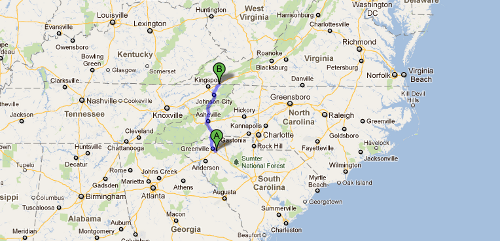

The last time L and I were in Rock Hill for a volleyball tournament, and Papa was still alive, I managed to find the first house I remember living in, the house Nana and Papa owned when they brought me home.

In the front was the same railroad-tie planter that Papa had built decades and decades ago, sometime in 1976 or 1977 I would imagine: I say this because I remember him building it, in vague, hazy memories that might be more the product of suggestion than actual memories.

When Nana passed away and I was going through all the old photos we’d taken from their condo, I found one of us cousins in front of that house. I’m on the little horse toy toward the far right; that’s my cousin C behind me. This was from a family reunion that we had at our house. I remember a family reunion there, so it must have been a second one: I’m far too young in this picture to remember anything from that time.

From the same series of pictures is one of my grandparents: Papa’s father is on the far left; Papa’s mother is the only woman in the foreground.

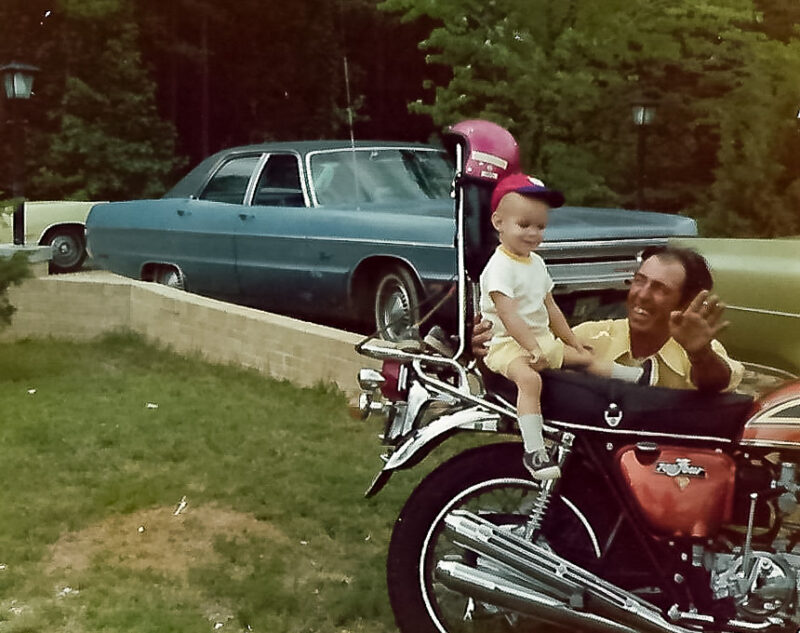

And yet another one from that day, this time on someone’s motorcycle. I’m not sure whose, and I’m not sure it was the owner posing with me in this shot, and I’m not sure who the man in the picture is. These are all just things that exist in my past but not in my memory.

And the obvious move: what pictures will have this same effect on my own children? Probably none — their lives are so completely documented here that they would have no problem figuring out who was holding them on a motorcycle…

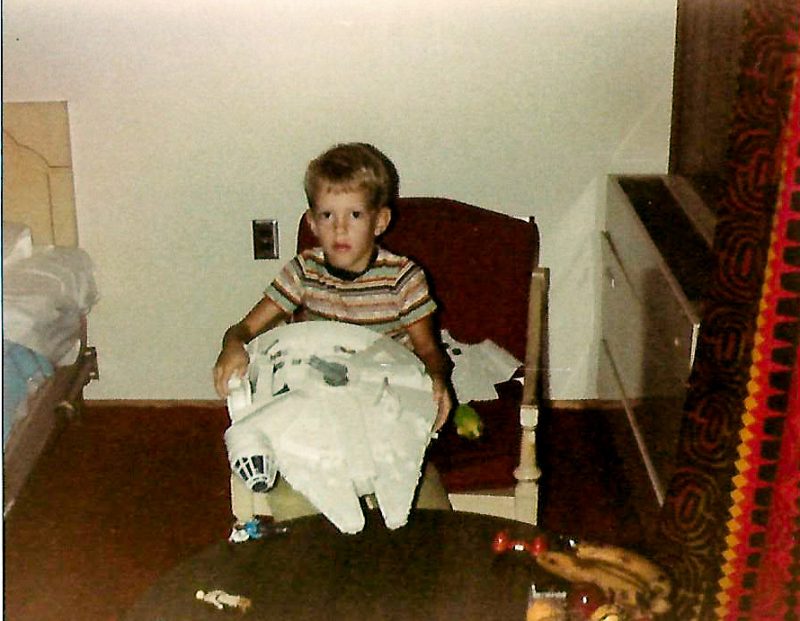

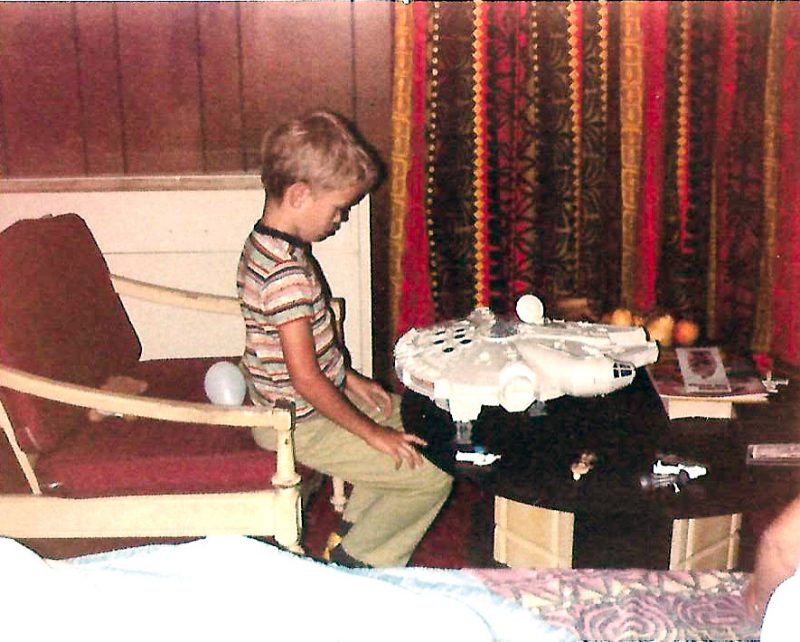

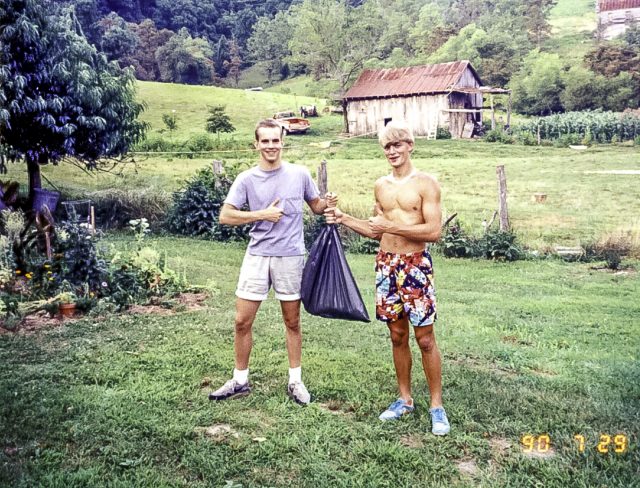

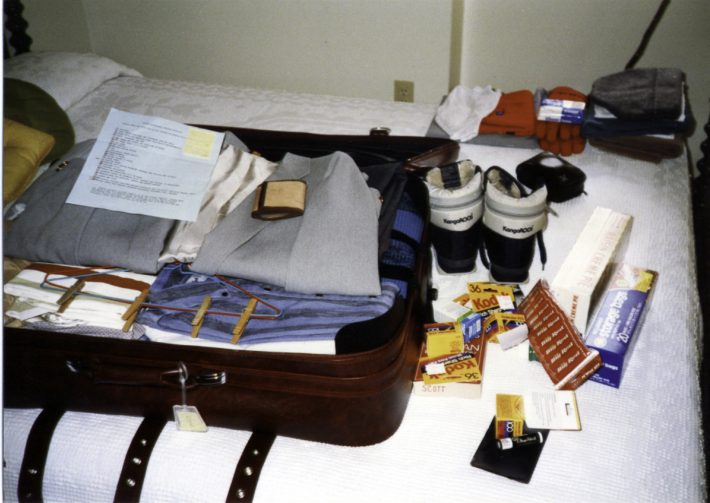

In the process of reorganizing the basement storage/work room, K and I have been tearing open boxes that have sat virtually untouched for years. Most of it consists of my own belongings, packed up while I lived in Poland in the late 1990s (eventually repacked into sturdy Rubber Maid storage bins). My parents moved, and instead of making the decisions for me, they left it to me, ten years later, to go through the stuff and toss out that which was once treasure but now trash. Granted, I could have done it earlier, but I lacked the serious motivation. Who wants to root around through old boxes of memories?

In the process of reorganizing the basement storage/work room, K and I have been tearing open boxes that have sat virtually untouched for years. Most of it consists of my own belongings, packed up while I lived in Poland in the late 1990s (eventually repacked into sturdy Rubber Maid storage bins). My parents moved, and instead of making the decisions for me, they left it to me, ten years later, to go through the stuff and toss out that which was once treasure but now trash. Granted, I could have done it earlier, but I lacked the serious motivation. Who wants to root around through old boxes of memories?

Her collection grows, and her eyes always light up when she gets a new book.

Her collection grows, and her eyes always light up when she gets a new book.