Teaching Eighth Graders

Exposure

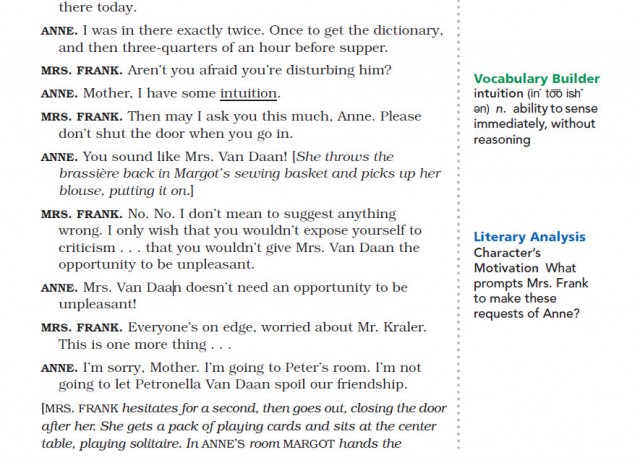

We’re in class, reading the play The Diary of Anne Frank, acting out some sections, comparing others to the original diary. Today, we’re working to analyze the text to determine places where one character implied something and/or another character inferred something. In the story, Anne and Peter’s romance is just beginning, and Anne is getting reading for an evening visit with Peter as she talks with her mother and sister in her room:

In groups, after we act it out, students analyze the text together to find specific lines (“You have to be able to point to it in the text,” I explained) that clearly show either an implication or inference.

As we’re debriefing as a class, a student points out one of the key lines I was hoping students would see: “Then may I ask you this much, Anne. Please don’t shut the door when you go in.” Mrs. Frank is of course not implying that she thinks that Peter and Anne will do anything untoward; she’s merely worried about giving Mrs. van Daan (in reality, her name was van Pels) something else to complain about.

The student didn’t see it that way, though.

“What is she implying?” I ask.

“That Anne will expose herself to Peter!” he said proudly, with utmost sincerity and seriousness.

We all laughed, but my own belly laugh got them laughing even harder.

Romeo, Wherefore Art Thou So Disappointing?

We’re knee-deep in Romeo and Juliet, as is always the case this time of year. One scene into act three, we’ve really hit the point in the play at which events start accelerating. Juliet will shortly embark on her gorgeous soliloquy about the dangers of taking Friar Laurence’s potion.

I have a faint cold fear thrills through my veins,

That almost freezes up the heat of life:

I’ll call them back again to comfort me:

Nurse! What should she do here?

My dismal scene I needs must act alone.

Come, vial.

What if this mixture do not work at all?

Shall I be married then to-morrow morning?

No, no: this shall forbid it: lie thou there.What if it be a poison, which the friar

Subtly hath minister’d to have me dead,

Lest in this marriage he should be dishonour’d,

Because he married me before to Romeo?

I fear it is: and yet, methinks, it should not,

For he hath still been tried a holy man.

How if, when I am laid into the tomb,

I wake before the time that Romeo

Come to redeem me? there’s a fearful point!

Shall I not, then, be stifled in the vault,

To whose foul mouth no healthsome air breathes in,

And there die strangled ere my Romeo comes?

Or, if I live, is it not very like,

The horrible conceit of death and night,

Together with the terror of the place,–

As in a vault, an ancient receptacle,

Where, for these many hundred years, the bones

Of all my buried ancestors are packed:

Where bloody Tybalt, yet but green in earth,

Lies festering in his shroud; where, as they say,

At some hours in the night spirits resort;–

Alack, alack, is it not like that I,

So early waking, what with loathsome smells,

And shrieks like mandrakes’ torn out of the earth,

That living mortals, hearing them, run mad:–

O, if I wake, shall I not be distraught,

Environed with all these hideous fears?

And madly play with my forefather’s joints?

And pluck the mangled Tybalt from his shroud?

And, in this rage, with some great kinsman’s bone,

As with a club, dash out my desperate brains?

O, look! methinks I see my cousin’s ghost

Seeking out Romeo, that did spit his body

Upon a rapier’s point: stay, Tybalt, stay!

Romeo, I come! this do I drink to thee.

Capulet will soon make his ultimatum to Juliet: marry Paris or be not my daughter!

Day, night, hour, tide, time, work, play,

Alone, in company, still my care hath been

To have her match’d: and having now provided

A gentleman of noble parentage,

Of fair demesnes, youthful, and nobly train’d,

Stuff’d, as they say, with honourable parts,

Proportion’d as one’s thought would wish a man;

And then to have a wretched puling fool,

A whining mammet, in her fortune’s tender,

To answer ‘I’ll not wed; I cannot love,

I am too young; I pray you, pardon me.’

But, as you will not wed, I’ll pardon you:

Graze where you will you shall not house with me:

Look to’t, think on’t, I do not use to jest.

Thursday is near; lay hand on heart, advise:

An you be mine, I’ll give you to my friend;

And you be not, hang, beg, starve, die in

the streets,

For, by my soul, I’ll ne’er acknowledge thee,

Nor what is mine shall never do thee good:

Trust to’t, bethink you; I’ll not be forsworn.

Of course the dual suicide scene, with Romeo’s melodrama: “Eyes, look your last!”

You’d think it’s the perfect play for thirteen-year-olds. It’s got so much pathos that it almost chokes you on it. Yet they’re beginning to find Romeo tiresome, and when he falls on the floor in Laurence’s cell in a few days, they’ll have lost the last shred of respect for him that they might have been clinging to.

It is, in a short, the highlight of my school year: students’ first real experience with Shakespeare and their budding recognition that they can make sense of his seemingly convoluted, inverted sentences, his arcane vocabulary, his foreign sense of propriety, and his unexpected sense of humor.

Reasons

It’s that time of year: Romeo and Juliet with the kids in the two sections of high school English I have the privilege of teaching. We’ve finished the second act, and today students took the act quiz. One element of the quiz is the quote identification.

“It’s not a question of memory,” I told them when I introduced the idea at the beginning of the unit. “It’s a matter of logic. I choose quotes that you can logically piece together and determine who said it.

They generally have done well, and this year’s group is no exception. Still, there are some who surprise me. For example, one quote from today’s quiz was Romeo’s response to Juliet about how he got there: “With love’s light wings did I o’erperch these walls; / For stony limits cannot hold love out[.]” One student explained it thus:

You know this is Romeo because he is the one who climbed over the Capulet’s wall to go to Juliet’s balcony. He is also the fatalist, so he would be the one that would do anything to see Juliet, even risking being caught or injury.

Another passage: “He jests at scars that never felt a wound.”

The person that said this line had to have been Romeo because when he says this about Mercutio, it’s directly after hearing him tease Romeo about his personality. He is justifying that Mercutio is saying these things because he does not know what it feels like. Mercutio would be the one to joke about Romeo’s love because he is the “joker”. Romeo is just testifying against what he says with an excuse for the reason Mercutio says this.

And just a few weeks ago, they claimed the could never understand the Bard.

Mark Up

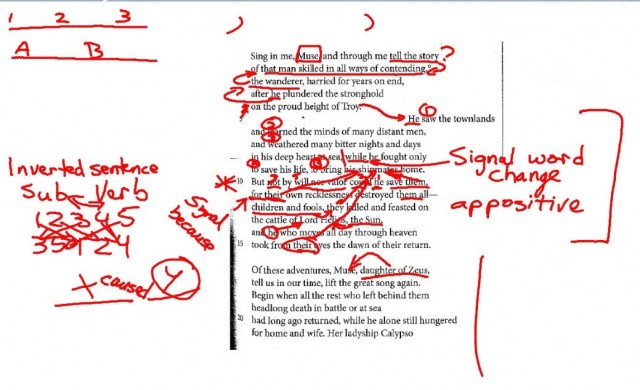

One class I teach — though I’m fortunate to teach two sections of this course — has begun one of my favorite pieces of literature, the Odyssey. Highly figurative language with a tendency toward oddly inverted sentences, it’s a struggle for them at first, though. We take the time during the first reading to pick apart the opening lines to see how Homer works.

The first famous lines include it all (in this particular translation). There’s inverted sentences like this: “But not by will nor valor could he save them.” We work through the sentence, determining the subject, the verb, and the object, writing it out in normal order: “He could not save them by will or valor.” Numbering the words, students realize just how inverted the sentence is.

“Lord Helios […] took from their eyes the dawn of their return” the stanza ends, and while many of us might find that easily enough understood, the average eighth grader doesn’t have a lot of experience with figurative language.

As we work, there’s a bit moaning, a bit of boredom, especially among the boys. Who wants to put this much effort into reading, and a poem at that? That’s alright. I know that when the blood starts flowing — Cyclops starts crunching bones and Scylla begins picking off men — they’ll all come around.

Floating on More than Survival

male sparrows putting on a show. by Will at Morro

The students sit during the Silent Sustained Reading with which we now conclude each day in our new schedule. We’ve begun the year reading the same book, a Pearl Buck short novella called The Big Wave, keeping a reader’s journal as we read. We’re all almost literally on the same page, which simplifies some of the logistics of the year-long project.

“Once you finish this book,” I tell the kids, “You can read whatever you want.” And so when I finish the book, I pick up a poetry collection and encounter R. T. Smith’s amazing poem (source):

Hardware Sparrows

Out for a deadbolt, light bulbs

and two-by-fours, I find a flock

of sparrows safe from hawksand weather under the roof

of Lowe’s amazing discount

store. They skitter from the racksof stockpiled posts and hoses

to a spill of winter birdseed

on the concrete floor. Howthey know to forage here,

I can’t guess, but the automatic

door is close enough,and we’ve had a week

of storms. They are, after all,

ubiquitous, though poor,their only song an irritating

noise, and yet they soar

to offer, amid hardware, ropeand handyman brochures,

some relief, as if a flurry

of notes from Mozart swirledfrom seed to ceiling, entreating

us to set aside our evening

chores and take grace wherewe find it, saying it is possible,

even in this month of flood,

blackout and frustration,to float once more on sheer

survival and the shadowy

bliss we exist to explore.

I think of all the linguistic hoops most of my students would have to jump through even to understand the poem let alone to find themselves floating themselves when they reach the final line. Then there is all the cultural knowledge they would need — chiefly, at least a rudimentary knowledge of the and familiarity with the music of Mozart. And the general motivation.

It’s at times like that that I understand just what it means to teach literature and writing in 2012 to fourteen-year-olds.

Tour Guide

When I start a favorite book with a class, I recall the weeks I was a tour guide for my folks and best friend from high school, all of whom flew to Poland for K’s and my wedding.

When I start a favorite book with a class, I recall the weeks I was a tour guide for my folks and best friend from high school, all of whom flew to Poland for K’s and my wedding.

I knew, for instance, as we rounded the bend and the Oravski castle (where Nosferatu was filmed; watch from 20:00-22:00 and 25:35-27:00 for the castle’s main scenes) came into view that everyone’s jaw would drop. Perched on the top of a rocky hill, the castle tends to have that effect on people.

Later, in Krakow, I knew what the reaction would be as we entered the Basilica of St. Mary on the market square. The high Gothic walls draw all gazes upward, and all mouths fall open.

So, too, with books. As we approach the shocking moments, the truly moving scenes, I anticipate students’ reactions. When Samneric tell Ralph that Roger has “sharpened a stick at both ends,” students ask, “Does that mean what I think that means?” When they meet Anne Frank in the pages of her diary, the knowledge of her fate shakes them.

Yet I’ve never seen a student react so emotionally to a novel as I did recently, as we read Nightjohn. It’s the story of a young slave girl who surreptitiously learns to read with from John, a slave who escaped north but returned to lead other slaves to literacy. There are some brutal depictions of violence against slaves, including the story of Alice, young girl who is whipped and then attempts escape. The pursuing slave owner finds her and lets his dogs attack. She survives, only barely.

“My heart hurts,” said a young African American girl who sits toward the back of the room. By the time the bell rang, a few tears were rolling. As she was leaving, I spoke to her, a little concerned.

“Are you going to be alright?”

“No,” she cried. She walked out of the class and completely broke down. As she sobbed, friends — who hadn’t been in class with her — crowded around her compassionately.

It was bittersweet, in the truest sense of the word. That someone was that moved by a book was both a source of hope and empathy.

Relativity

Rereading Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom! (the greatest achievement in American literature), I’ve realized anew how relatively temporally close Quentin is the events Rosa Coldfield is relating. Coldfield relates the story of Sutpen to Quentin (though he knows it already — it’s in his blood from growing up in Jefferson) in 1910, and Coldfield makes it clear that Sutpen was the reason God saw fit to let the South lose the war. Coldfield wants Sutpen’s story told so that those

who have never heard her name nor seen her face will read [the story of Sutpen] and know at last why God let us lose the War: that only through the blood of our men and the tears of our women could He stay this demon and efface his name and lineage from the earth.

It is, in other words, a story of the Civil War. And while that seems so very distant to us now, it’s easy to understand the lingering resentment Southerners feel in the story. After all, it’s only been forty-some odd years since the war when Quentin sits in Coldfield’s house, listening to the story of the most mysterious man in the county.

For us today, that’s the nearness of the Vietnam War, something that’s still in most everyone’s cultural consciousness. Many are still upset about “Hanoi Jane,” and I suppose that resentment might be something akin to what Coldfield is feeling in the novel: a resentment of a defeat that seems due to so many non-military, non-combat reasons.

Yet it’s still difficult for me to understand the continuing resentment many white Southerners feel about a defeat that was almost a century and a half ago. “The South will rise again!” would have made sense in Quentin’s turn-of-the-century culture, but another century after that and so many are still boiling about it?

Then again, a century and a half is nothing compared to the length and depth of some of Europe’s ethnic and national resentments. Hatred and disappointment never die, I suppose.

Madeline

In an old house in Paris that was covered with vines,

lived twelve little girls in two straight lines.

They left the house at half past nine […]

The smallest one was Madeline.

Madeline is fast becoming one of L’s favorites. We only own one book (Madeline’s Christmas), but we’ve borrowed several from the library, all of them hits. And what’s not to love about them? Lovely stories and a recurring theme: don’t judge by appearances.

Lately, L’s been fascinated with the Madeline cartoon. So far as adaptations go, these cartoons are wonderful. Christopher Plummer as the narrator has a warm, grandfatherly voice.

It seems to worm its way into your heart and stay there:

This show hasn’t been popular since I was in kindergarten. I am almost thirteen now, and sometimes, when I am up late, I stumble across “Madeline” on the Disney channel. I loved this show when I was little and I wonder why they don’t show it at times when little children can see it. It’s a lot better than the junk they show on “Playhouse Disney” these days. (Koala Bros., Higglytown Heroes, etc.) If they could bring this show back, it would be just as popular, if not, more than it once was. I think that Madeline had a big influence on children between the ages of two to six. Heck, I would still watch it. I hope to see Madeline on Disney Channel really soon. (IMDb)

The best part: the theme song. We’re all going around singing it.

Eighth Grade Shakespeare

Shakespeare is a challenge to our modern ears, no doubt about it. Even the most knowledgeable experts halter a line or two of a performance before they settle in to the poetry. In my experience, it takes me about a few minutes before the language on stage sounds completely natural and non-foreign.

I’ve been teaching Shakespeare to eighth graders of various academic levels for the past week: an enlightening, frustrating, ultimately rewarding experience. We’re reading an abridged version of Much Ado About Nothing. It is, in fact, part of the required eighth grade curriculum here in Greenville County, and I’m thrilled that those who designed the curriculum had the wisdom of chosing a comedy rather than, say, Julius Caesar. (A perfectly fine play in its own rights, it’s an absolute bore to teenagers.) Much Ado has all the elements adolescents can relate to: unrequited love; jealousy; the twittery, jittery joy of new love.

Yet it’s still been difficult enough for them that it’s been, at times, a chore. And so to remedy that, I changed my unit plan and decided to show the Branaugh Much Ado concurrently with our own reading. We’ve completed the first two acts in class; we watched the first two acts today.

What a joy to watch the kids watch Shakespeare and enjoy it. What was most rewarding for me was to hear them laugh at lines that had been omitted from our abridged version. “They’re really getting it,” I almost said aloud.

Identifying Passages

As part of our recent test on Romeo and Juliet, I included seven passages from the play for identification.

The instructions:

Identify the following passages. Who is the speaker? To whom is he/she speaking? How is this a critical passage in the play?

- A plague on both your houses!

- I pray thee, good Mercutio, let’s retire:

The day is hot, the Capulets abroad,

And, if we meet, we shall not scape a brawl;

For now, these hot days, is the mad blood stirring. - Compare her face with some that I shall show,

And I will make thee think thy swan a crow. - ‘Tis but thy name that is my enemy;

Thou art thyself, though not a Montague.

What’s Montague? it is nor hand, nor foot,

Nor arm, nor face, nor any other part

Belonging to a man. O, be some other name!

What’s in a name? that which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet; - There is no world without Verona walls,

But purgatory, torture, hell itself. - What if it be a poison, which the friar

Subtly hath minister’d to have me dead,

Lest in this marriage he should be dishonour’d,

Because he married me before to Romeo? - Death, that hath suck’d the honey of thy breath,

Hath had no power yet upon thy beauty:

Thou art not conquer’d; beauty’s ensign yet

Is crimson in thy lips and in thy cheeks,

And death’s pale flag is not advanced there.

Some are easy; at least one is a little obscure (but covered in class as one of many examples of the Bard’s incessant foreshadowing).

See how many you can get. No Googling!

Billy Collins

I have not been “into” poetry for some years now. I once thought I might be a poet at heart, but I can’t even write compelling blog entries, so that is a dream long lost.

I do have to teach poetry, though, and I discovered, while teaching a unit on imagery, my new favorite poet: Billy Collins. Poet Laureate from 2001 to 2003, he is accessible, witty, and charming.

The poem we read in class was “The Country.” While searching for an online version, I found an animated version of the poem. Then, I discovered “Forgetfulness.” It has all the elements of a poem of genius: enlightening observations, a uncommonly commonplace topic, perhaps even a cliche turned inside out.

The Bard on the Wane

In a study entitled “Vanishing Shakespeare,” the American Council of Trustees and Alumni found that 55 out of 70 “English departments at the U.S. News & World Report‘s top 25 national universities and top liberal arts colleges, as well as the Big Ten schools and select public universities in New York and California” don’t require English majors to take a course in Shakespeare. Instead, we’re replacing the Bard with Madonna:

Increasingly, colleges and universities envision a major in English not as a body of important writers, genres, and works that all should know, but as a hodgepodge of courses reflecting diverse interests and approaches. See Appendix B.) After redesigning the English major at the University of Pennsylvania, for example, the department’s undergraduate hairman told The Daily Pennsylvanian student newspaper that We might not agree on what we think English is, but we could all agree that our curriculum should reflect the makeup of our faculty. Such a philosophy results in course offerings being driven not by the intellectual needs of students, but often by the varied interests and agendas of the faculty. As a consequence, it is possible for students to graduate with a degree in English without thoughtful or extended study of central works and figures who have shaped our literary and cultural heritage.

It’s difficult for me to imagine not studying Shakespeare as an English major. Shortly after I graduated, the professor who taught the Shakespeare course at my small liberal arts college introduced a second Shakespeare course in which students spent a whole semester studying a single play, with the ultimate aim of performing it. It was offered every other year, with a more traditional, 12-play Shakespeare course offered on off years. I wish I’d had the opportunity to take both.

But not to study his work at all? “A degree in English without Shakespeare is like an M.D. without a course in anatomy. It is tantamount to fraud.”

Madeleine L’Engle

Madeleine L’Engle, author of one of the most famous books in the adolescent literature canon, A Wrinkle in Time, died last week. (Madeleine L’Engle: News)

A Wrinkle in Time was one of the first science fiction books I ever read, and it’s one that has stayed with me for twenty-some years now. I read it again in college for the required course on adolescent lit, and it was just as enchanting in my early twenties as it had been twelve or so years earlier.

Potter v Pope

In Poland, the Catholic Church is very much against Harry Potter — sort of like religious conservatives here.

Why?

We all know the standard reasons: wizards and sorcery are simply forbidden in the Bible. It’s that simple.

Yet K pointed out the “real” reason Potter worries the Polish church. I read the BBC News article opening to her:

The seventh and final Harry Potter book has broken sales records on both sides of the Atlantic, selling 11 million copies in its first 24 hours.

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows sold 2.7 million copies in the UK and 8.3 million in the US. (BBC)

She responded, “See, that’s why the Polish church is so scared of Harry Potter. That’s real power.”

Reading List

Frederick Wirth writes in Prenatal Parenting of an experiment Anthony Casper conducted at the University of North Carolina regarding parental reading and prenatal development. He had mothers read Dr. Seuss’ The Cat in the Hat to their unborn children twice a day. A few days after birth, the infants were given a chance to hear the story again. However, using a device fitted with a special nipple, the infants could change the story being read by changing the rate at which they were sucking.

As demonstrated by their sucking speed, the newborns remembered The Cat in the Hat better. Furthermore, they preferred it read forward instead of backward. (Wirth, 37)

So I guess in a way I was wrong when I suggested that our daughter might prefer Shell Silverstein to Robert Frost.

Or, looking at it another way, here’s a chance to get my daughter interested in all the nerdy literature I love.

Of Mans First Disobedience, and the Fruit

Of that Forbidden Tree, whose mortal tast

Brought Death into the World, and all our woe,

With loss of Eden, till one greater Man

Restore us, and regain the blissful Seat,

Sing Heav’nly Muse

I aim to give L a headstart on senior lit…

Reading and Walls

In my “Currently Reading” pile of books lies Prenatal Parenting by Frederick Wirth, M.D. Most interesting so far have been the sections on fetal sensory development, particularly the development and growth of the auditory system. Wirth writes that at “twenty-two weeks of gestation the developing infant will respond to sounds from outside the womb. By twenty-eight weeks the infant responds to sound in very consistent ways.” (28) And so K talks to her walk driving to work, and I press my cheek to K’s belly nightly and tell our daughter how much we’re looking forward to meeting her.

In my “Currently Reading” pile of books lies Prenatal Parenting by Frederick Wirth, M.D. Most interesting so far have been the sections on fetal sensory development, particularly the development and growth of the auditory system. Wirth writes that at “twenty-two weeks of gestation the developing infant will respond to sounds from outside the womb. By twenty-eight weeks the infant responds to sound in very consistent ways.” (28) And so K talks to her walk driving to work, and I press my cheek to K’s belly nightly and tell our daughter how much we’re looking forward to meeting her.

K and I have been playing a little music box for our daughter nightly for some weeks now, but recently, we’ve added reading to the ritual.

It should have a noticeable effect:

I can always tell which of my full-term newborn infants have been read to. They have more mature orienting behavior to auditory stiumli. I can even tell which fathers have been active in reading to their unborn child. I do this by holding the infant between me and his father while we compete for the infant’s attention by calling the child’s name. If the dad has been actively involved in the reading and singing, his child will turn his head toward him, looking for the source of the sound. Invariably, when their eyes meet they both react positively. (Wirth, 29)

Often, it’s selections from Where the Sidewalk Ends, not so much because L will like it more — obviously, fetal brain development at this point is not that advanced — but because K likes Silverstein’s playful language.

Often, it’s selections from Where the Sidewalk Ends, not so much because L will like it more — obviously, fetal brain development at this point is not that advanced — but because K likes Silverstein’s playful language.

Tonight, Robert Frost, concluding with one of his best, one of the best, period: “Mending Wall.” It has one of the truest passages ever written:

Before I built a wall I’d ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offence.

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That wants it down.’

Such concerns seem largely forgotten these days.

Writing about Literature

Why am I no longer interested in studying literature? Is it simply that I don’t understand most of it, particularly contemporary poetry? Perhaps, but regardless of whether I understand it or not, it all feels so fake to me, so much like a game. The rules of the game are simple: Make nice flowery language that doesn’t necessarily mean anything in particular; make nice vague language that sounds nice but doesn’t necessarily many anything. It’s as if poets are not writing for people but for other poets. Even the criticism and analysis of poetry seems as if it’s coded for poets. I read descriptions of poetry and it tells me nothing. I understand what the words mean, but I don’t see how you can possibly describe poetry in that way and it mean anything. In that way, poetry critism is its own form of creative writing. No one simply says, “This is what the poet is getting at,” but the critic must turn her essay into a prose-poem itself.

Take for example Christian Wiman’s essay in the January 1997 issue of Poetry. He says of Heaney’s “The Harvest Bow,” “The poem has an equable, utterly accomplished feel to it, a pleasing sense of formal fulfillment and completed experience.” Or comparing Heaney’s work to Ruskin’s “sacred laws”: “Both are as yet unrealized, but they are not merely illusory expectations; the promised revelation is implicit in the work at hand.” Of course I am taking these quotes completely out of their context and not even supplying the poems about which Wiman is writing. All the same, while I understand what each word means, the sentences themselves tell me nothing about the poems. In what sense are they “unrealized?” How would an “utterly accomplished feel” differ from a “partially accomplished feel?” Indeed, what would be the opposite of “an utterly accomplished feel?” The words sound nice; they sound academic and deep; but they don’t tell me anything.

The Vintage Book of Contemporary American Poetry is filled with examples of empty and meaningless description. J. D. McClatchy, the editor, writes a brief biographical introduction to each poet, but when he sets about describing the poetry, he often loses me. He introduces Mora Van Duyn by saying, “Her intellectual balance, as well as her preferred narrative and formal strategies, serve to heighten the ordinary (what she calls the ‘motley and manifold’), and control the bizarre.” What exactly does he mean by “intellectual balance” and how does this manifest itself in Van Duyn’s poetry? He describes Robert Penn Warren’s later poetry as “craggy.” This tells me nothing.

Some of McClatchy’s description makes sense, but seems to be more than a little overstated. Concerning J. V. Cunningham, he says, “Though small in bulk and scope, Cunningham’s work is honed to a mordant precision of style and feeling.” I read this, and I have no idea what he’s talking about. Even after I read Cunningham’s poetry, I think, “How does McClatchy mean this is ‘honed to a mordant precision?’” Not all of Cunningham’s work is filled with the biting sarcasm implied in “mordant precision.” And once again, what would the opposite be?

It is not as if McClatchy writes entirely like this. About May Swenson’s work he says that she “relies on wordplay, odd viewpoints, unexpected juxtapositions, and puzzling riddles.” That tells me something; it gives me an idea about what to expect concerning her poetry. He describes Richard Wilbur’s work as being “grounded in a detailed observation of the natural world.” I read that I come to anticipate many physical details in his poetry.

I believe this style comes directly from the forms used by poets when they write about other poets. Robert Lowell wrote to Theodore Roetke and said, “One of the things I marvel at in your poems is the impression they give of having been worked on an extra half day.” What does that tell me about Roethke’s poetry? About Anne Sexton Lowell wrote, “Her gift was to grip, to give words to the drama of her personality.” The latter half I understand, but what does he mean, “to grip?” To grip what?