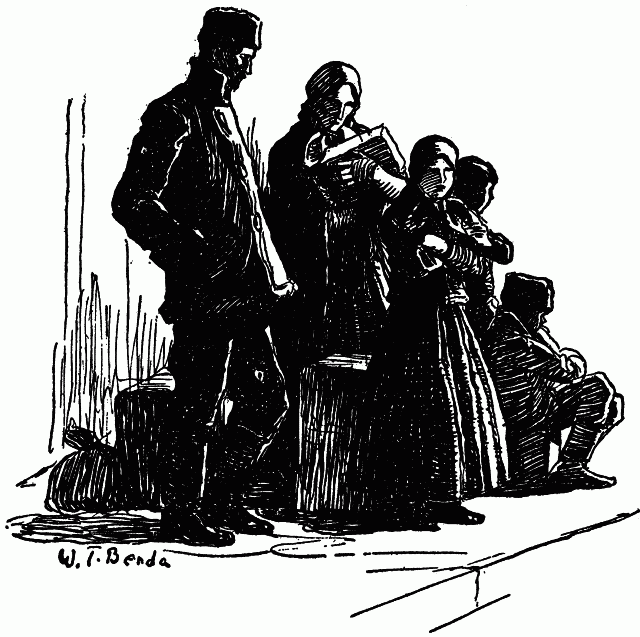

They always miss it — that one detail that changes everything about the ending of To Kill a Mockingbird. It’s so small, yet it tells us so much, and it’s a sign of how good an author Harper Lee was. She sets up the situation with a misdirection:

“Mr. Finch.” Mr. Tate was still planted to the floorboards. “Bob Ewell fell on his knife. I can prove it.”

Atticus wheeled around. His hands dug into his pockets. “Heck, can’t you even try to see it my way? You’ve got children of your own, but I’m older than you. When mine are grown I’ll be an old man if I’m still around, but right now I’m—if they don’t trust me they won’t trust anybody. Jem and Scout know what happened. If they hear of me saying downtown something different happened—Heck, I won’t have them any more. I can’t live one way in town and another way in my home.”

Mr. Tate rocked on his heels and said patiently, “He’d flung Jem down, he stumbled over a root under that tree and—look, I can show you.”

Mr. Tate reached in his side pocket and withdrew a long switchblade knife.

We assume that Tate is going to show Atticus how Bob Ewell fell on his knife, and he does just that.

Mr. Tate flicked open the knife. “It was like this,” he said. He held the knife and pretended to stumble; as he leaned forward his left arm went down in front of him. “See there? Stabbed himself through that soft stuff between his ribs. His whole weight drove it in.”

Mr. Tate closed the knife and jammed it back in his pocket. “Scout is eight years old,” he said. “She was too scared to know exactly what went on.”

But that’s not the reason Lee includes that detail. The real reason comes into focus a few paragraphs later:

“Heck,” said Atticus abruptly, “that was a switchblade you were waving. Where’d you get it?”

“Took it off a drunk man,” Mr. Tate answered coolly.

I was trying to remember. Mr. Ewell was on me… then he went down… Jem must have gotten up. At least I thought…

“Heck?”

“I said I took it off a drunk man downtown tonight. Ewell probably found that kitchen knife in the dump somewhere. Honed it down and bided his time… just bided his time.”

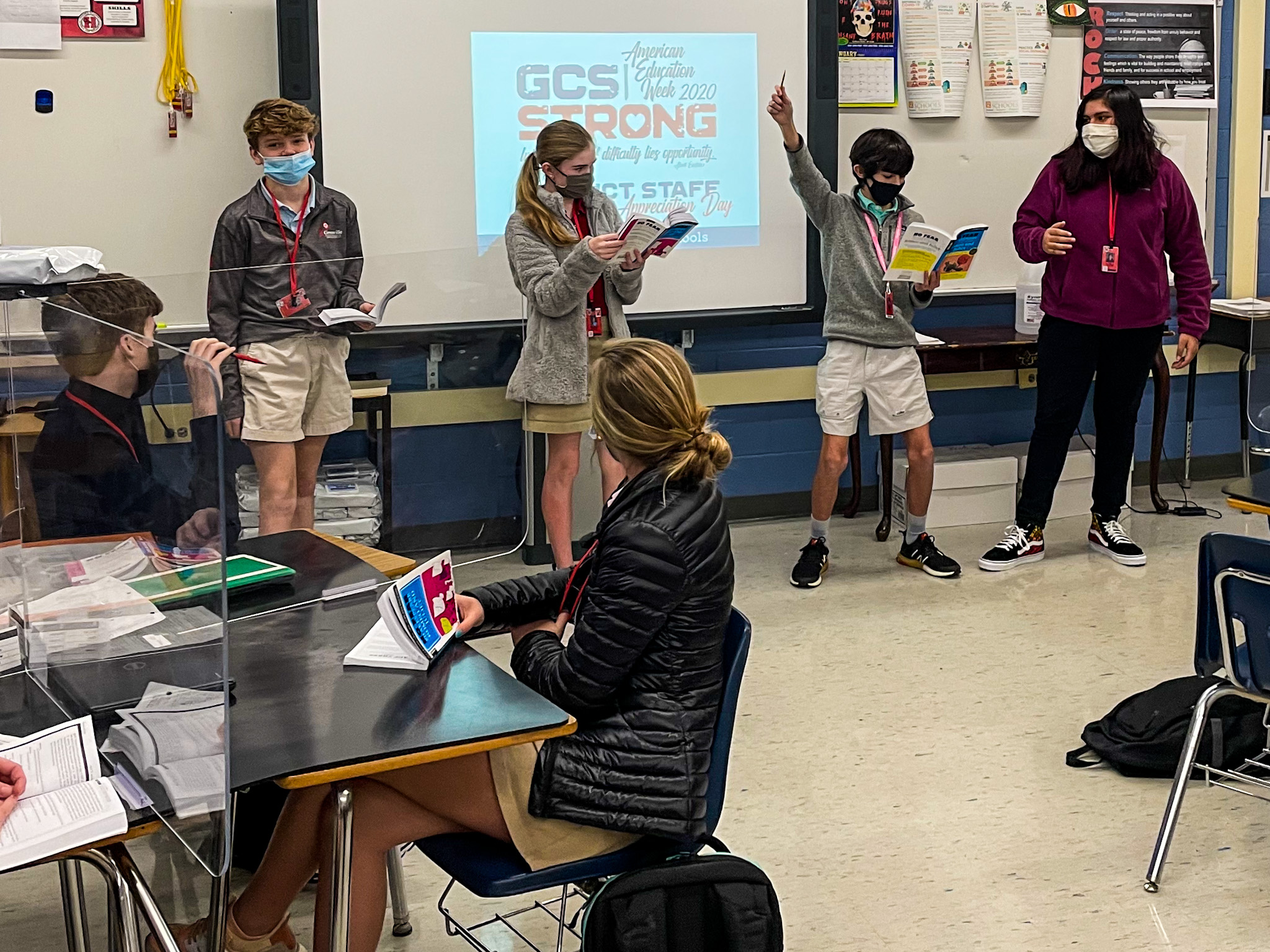

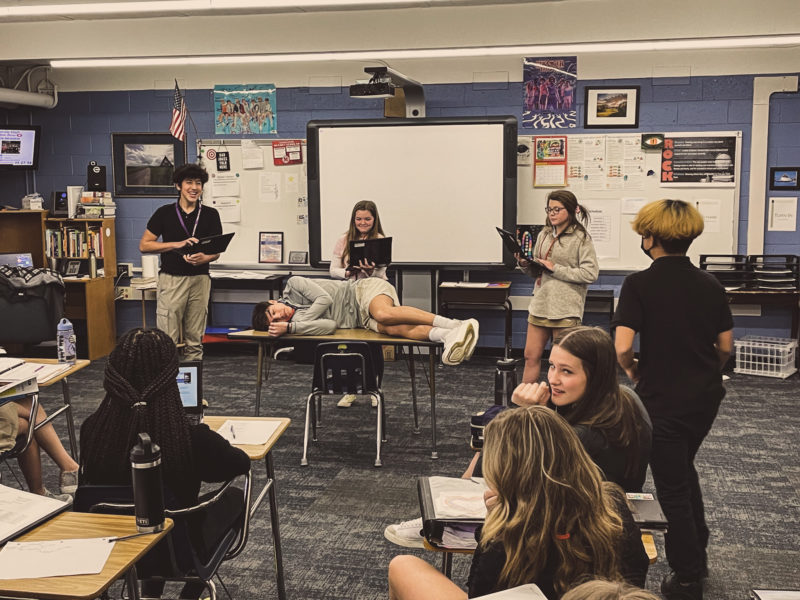

The kids were working on it today, and I pointed out that there’s a detail that makes everything different, changes the whole story. “No one has ever managed to see it,” I challenged them, and it’s true: most kids read right over that detail:

“Heck,” said Atticus abruptly, “that was a switchblade you were waving. Where’d you get it?”

“Took it off a drunk man,” Mr. Tate answered coolly.

The drunk man he took it off was Bob Ewell. When Tate arrives to investigate the body, he finds Bob Ewell lying on the ground, a knife in his craw, as he puts it, and a switchblade in his hand. In order to cover up Boo Radley’s involvement, he has to take the switchblade. He tampers with evidence to protect Boo Radley.

Today, though, one girl almost got it. “Mr. Scott, I think it’s something to do with this knife,” she said. She’d read the passage and knew something felt off. What felt off? It’s a detail that doesn’t seem to be connected to anything, and Lee brings it up twice, which means it must be important. I just smiled in response. “Could be something important.”

Later in the day, a couple of hours after class in fact, she emailed me:

I think that the switchblade was Bob Ewells and Heck heard the kids getting attacked and came to the scene and took the switchblade from Bob then Boo Radley, who can see very well in the dark, used a kitchen knife to kill Bob Ewell, making it look like Bob tripped and his death was an accident.

I’m not completely sure if this is right but I have a feeling it is.

“So close,” I replied.

We’ll see tomorrow if she got it.

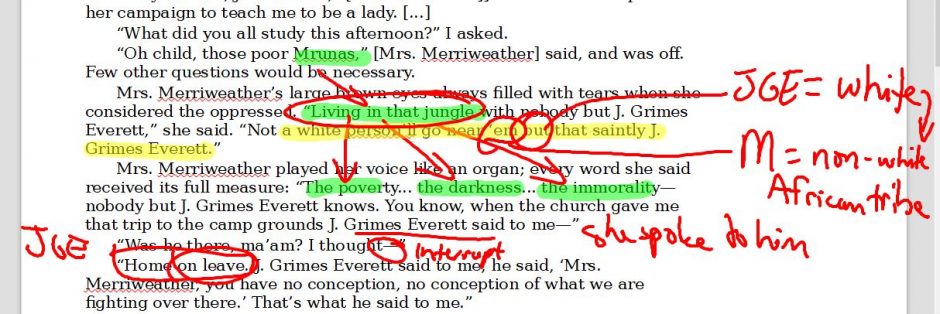

Students today finished working on the enigmatic twenty-fourth chapter of Mockingbird, which includes this passage that stumps all the kids every year:

Students today finished working on the enigmatic twenty-fourth chapter of Mockingbird, which includes this passage that stumps all the kids every year: