The first time I attended a church other than the one I grew up in, I was shocked at how utterly different the service was compared to what I was used to. When the pastor began, “Our scripture for today is…”, I immediately began wondering how in the world one could possibly have a sermon with one scripture. I was so accustomed to sermons that often amounted to an artillery barrage of verses that having a sermon with only one verses seemed like having a car with only one wheel.

As I visited other churches, I found that not only did every denomination have its own liturgy but also every single church within a denomination might have its own version. Going to churches in other countries, I imagined, might uncover even more differences.

Today, one can find a liturgy to fit whatever mood one might be in. Looking for something heavy on entertainment? Head to the nearest mega-church. Looking for a calm, quiet, predictable service? Look for Methodists or Presbyterians. Want a little danger in your worship? Seek out the few remaining snake-handling, strychnine-drinking Pentecostals in the hills of Appalachia.

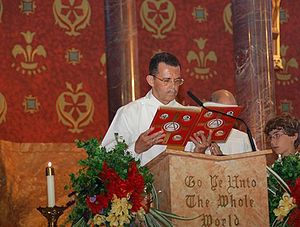

The Catholic Mass, however, is different because it’s the same. No matter the country, no matter language, no matter the culture, the Mass is the same. Before Vatican II and the introduction of Mass in the vernacular, it would literally be the same wherever one went. And here’s the thing that really impresses me: it’s been that way for centuries. The Mass of today would be recognizable, more or less, to Thomas Aquinas as much as it would be to G. K. Chesterton. Certainly, the hymns would be different, and the use of the vernacular (as opposed to Latin) would probably seem odd, but the heart of the Mass itself would be comfortingly familiar to both men.

I realize I’m using broad strokes here: there are certainly minor cultural differences in the Mass, and the Catholic church isn’t the only church to achieve this liturgical homogeneity. But one thing is certain: it’s had this homogeneity longer than any other institution in the West, and there’s something to be said for an institution that can be that grounded in the past and the present.