Lenten fail…

Lent 2012: Day 13

Yesterday’s reading at Mass was one of the most famous in Scripture: the commanded sacrifice of Isaac. Here’s a thought experiment I wrote over fifteen years ago when I was still in college.

Some time later God tested Abraham. He said to him, “Abraham!” “Here I am,” he replied. Then God said, “Take your son, your only son, Isaac, whom you love, and go to the region of Moriah. Sacrifice him there as a burnt offering on one of the mountains I will tell you about.”

Some time later God tested Abraham. He said to him, “Abraham!” “Here I am,” he replied. Then God said, “Take your son, your only son, Isaac, whom you love, and go to the region of Moriah. Sacrifice him there as a burnt offering on one of the mountains I will tell you about.”

So begins one of the most extraordinary stories in literature. The story of God’s command to Abraham to sacrifice Isaac is undoubtedly one of the best known Biblical stories. Soren Kierkegaard says, “The story of Abraham is remarkable in that it is always glorious no matter how poorly it is understood.” Indeed, it is an amazing story of faith and an incredible testament of ultimate trust in God.

One wonders, though, how the story might have changed had Abraham said, “No” to God’s command. The possibilities are endless, for there are so many variables. God might simply have accept the answer and go off in search of someone else to become the Father of the Faithful. He could roar, “How dare you defy me!” and strike down Abraham in fiery wrath. God might take a more human approach and beg: “Ah, come on. Trust me; I know what I’m doing!”

However, before pondering God’s response, one would have to take into account Abraham’s reason for refusing to follow God’s command. Perhaps it would be for selfish reasons. After all, Isaac is Abraham’s only offspring, a miracle child born when Sarah was well beyond child-bearing years. It is only natural for Abraham to cling stubbornly to his only child; certainly, old age would prevent Abraham and Sarah from having another. Possibly it would spring from incredible love for Isaac: “I’ll not do that to my son!”

Or it could be because Abraham feels homicide is wrong. He could shake a fist at God, declaring, “No! I will not kill, for any reason. I will not violate my conscience for any reason, not even divine command.”

This produces an entirely new possibility in the historical story of Abraham: God’s test of Abraham is open-ended. When God commands, “Take your son, your only son, Isaac, whom you love, and . . . Sacrifice him . . . as a burnt offering” God might be willing to accept either answer, “Yes” or “No.”

Once Abraham submits to God’s injunction, then there is no change from the actual account found in Genesis. Abraham is still regarded as the Father of the Faithful and the Bible remains in its present form.

If, however, Abraham refused on the grounds that the commanded act – murder – violates his conscience, God could respond, “I swear by myself that because you have done this and have not compromised your conscience for any reason, I will surely bless you and make your descendants as numerous as the stars in the sky and as the sand on the seashore.” Abraham would then become the Father of the Morally Steadfast. The entire Bible might be radically and totally different. Wholly different lessons would be learned from the story of Abraham. James 4.17 might read, “Anyone, then, who knows the good he ought to do and doesn’t do it, sins. For Abraham did what he knew to be right in his heart, even when God commanded otherwise.”

A series of questions then arises: If it was an open-ended test, what was God hoping it would reveal about Abraham’s character? If either obedience or disobedience was acceptable in this particular instance, what was God looking for in Abraham’s response? The only answer is passion. God was simply looking for someone who would act vigorously, someone who was zealous and complete in his actions. Whether or not Abraham was obeyed would not have mattered, for obedience could be learned more easily than zeal.

God has a way of changing people’s minds, but usually, they are already zealous in their activities, such as the apostle Paul or Jonah. Both men lived lives violently opposed to what God ultimately desired of them but both were dynamic and spirited in what they did. Jonah ran from God and his destiny and Nineveh with all the strength he could muster, and Paul persecuted the early Christians mercilessly, with every ounce of his strength. In both cases, God turned the men around and put them to his work, which they accomplished with even greater vigor, for they were now working toward a goal instead of running away from one.

This kind of passion could be exactly what God was looking for in Abraham. What God sought was a man who would be decisive and would back up the choices made with all his energy, ready and willing to accept the consequences of each action. God didn’t want someone apathetic, someone lukewarm.

Of course, Abraham did not say, “No.” He obeyed God even when it made no sense to him, even though God was asking him to do something from which there seemed to be nothing good that could arise, something ridiculously absurd. Some would label it blind devotion. Others call it faith. It is a kind of faith that to most of us in the twentieth century find alien, for there would be few – if any – people today willing to commit himself so fully to God’s will. Many people are not able – or willing – to understand why Abraham did what he did. Antagonists of Christianity point to this story as evidence of the absurd cruelty represented in the Bible, in an attempt to discredit the Bible as barbarous and antiquated. Yet the story records Abraham’s faith to the disbelief and astonishment of readers throughout the centuries.

The fact that Abraham did not disobey God makes the story even greater, adding immeasurably to its authority and puissance. It is a story of strength, of a strong man passing a test offered by an infinitely mighty God. Even the most fervent Christian must sometimes feel a little apprehensive about serving a God who would ask so much of one person, and this apprehension leads to great respect for Abraham and his faith. Underlying all of this is the question, “How could God ask such a thing, and how could Abraham obey such a ludicrously evil command?” It is the same question that antagonists of the Bible ask in an attempt to discredit the Bible. There must be an answer that glorifies the Bible and God. Yet it is sometimes difficult to get beyond the command itself and to understand the motivation of it’s charge and the power of Abraham’s obedience.

While talking to a friend about the magnificence of the story of Abraham and Isaac I was presented with a startlingly beautiful answer to this delimit. The test was not supposed to prove anything to God – the test was simply for Abraham to realize the power of his own faith. As God is spirit and outside of time, he would have been able to know exactly what Abraham’s response would be. Not only that, but God’s omnipotence would allow him to see inside Abraham’s heart to behold the energy of faithful obedience pulsing deep within Abraham’s being, out of even Abraham’s knowledge. It took such a powerful test as God gave to bring into fruition such a powerful force as Abraham’s faithful obedience.

Both Biblical precedence and common sense underscore the logic of this position. God commands obedience and the Bible is the story of those who obeyed and those who disobeyed. Always God rewards those who submit to his will and do what he commands. He didn’t reward Jonah for running. He didn’t reward Paul for persecuting. Yet he did reward Abraham for his obedience.

From a common-sense position, to say that the test was for God’s sake is ridiculous, for God knows everything. He is outside of time, therefore knows the future, present and past all simultaneously. God is omnipotent, all-knowing – there was nothing that he could learn from Abraham’s response that he didn’t already know from the beginning of time.

On the other hand, to say that the test was for the sake of Abraham works either way – God wanted to prove to Abraham his own moral fortitude of his own powerful faith. God, being outside of time, knew Abraham’s reaction long before Abraham was even born. God, therefore, knew the quality his test was to exemplify for as equally long. Accordingly, God knowing Abraham’s reaction does not disqualify the submission that the test was open-ended.

Lent 2012: Day 11

Religious people are an unkindly lot. Poor human nature cannot do everything; and kindness is too often left uncultivated, because men do not sufficiently understand its value. Men may be charitable, yet not kind; merciful, yet not kind; self-denying, yet not kind. […] Kindness, as a grace, is certainly not sufficiently cultivated, while the self-gravitating, self-contemplating, self-inspecting parts of the spiritual life are cultivated too exclusively.

One immediately assumes that charity is a sort of kindness, as is mercy. Faber suggests that it isn’t. Perhaps I don’t understand what Faber means by “kindness” after all.

The quoted excerpt is from Father Frederick Faber’s Spiritual Conferences, excerpted here.

Lent 2012: Day 10

[Kindness] watches the thoughts, controls the words, and helps us to unlearn [youth’s] inveterate habit of criticism.

Criticism is easy, fun even. We can easily discern others’ faults, and it takes little imagination to capitalize on these faults, aggrandizing ourselves while belittling others. As the fictional critic Anton Ego says in Ratatouille,

Criticism is easy, fun even. We can easily discern others’ faults, and it takes little imagination to capitalize on these faults, aggrandizing ourselves while belittling others. As the fictional critic Anton Ego says in Ratatouille,

In many ways, the work of a critic is easy. We risk very little, yet enjoy a position over those who offer up their work and their selves to our judgment. We thrive on negative criticism, which is fun to write and to read. But the bitter truth we critics must face, is that in the grand scheme of things, the average piece of junk is probably more meaningful than our criticism designating it so.

Yet when we’re practicing active kindness, it puts a filter over our lips.

The quoted excerpt is from Father Frederick Faber’s Spiritual Conferences, excerpted here.

Lent 2012: Day 9

A proud man is seldom a kind man. Perhaps nothing more needs to be said — especially considering how tired I am…

The quoted excerpt is from Father Frederick Faber’s Spiritual Conferences, excerpted here.

Lent 2012: Day 8

Thus does kindness propagate itself on all sides. Perhaps an act of kindness never dies, but extends the invisible undulations of its influence over the breadth of centuries.

“We can only plant the seeds. We never know how they will grow” It’s a common refrain in teaching, and I always kind of thought it was a cop-out. At times I feel like, quite frankly, such a failure as a teacher. Kids spend 180 days with me, and some of them seem none the better for it. It’s perhaps a useful guilt: it might spur teachers to become better at their job, to seek training and experiences that will increase their effectiveness.

Perhaps an act of kindness never dies

But saying, “We can only plant the seeds” seems somehow to alleviate that guilt. We plant the seeds; it’s up to the kids to tend the resulting crop.

Faber suggests otherwise: it’s not a cop-out. We can sow kindness and know, with some certainty, that it will grow into more kindness. We can know that we’ve had a positive impact on someone’s life. Perhaps it’s a good sign that we’re more willing to admit the opposite, or maybe it’s just another sign of our condition.

The quoted excerpt is from Father Frederick Faber’s Spiritual Conferences, excerpted here.

Lent 2012: Day 7

I think, with the thought of the Precious Blood, I can better face my sins at the last judgment, than my unkindness, with all its miserable fertility of evil consequences.

Unkindness is easier than kindness, and sometimes more rewarding in a perverse sense, much like heroin is more “rewarding” than a draft of water. But once the high wears off, we look back at that cutting remark or that sneering body language and think ourselves most wretched. We don’t often lie in bed, unable to drift to sleep for the thought of some kindness we shared or even at the thought of some bit of apathy that helped us slide through the day. But unkindness has left me turning in bed and occasionally haunted me into the early morning.

The quoted excerpt is from Father Frederick Faber’s Spiritual Conferences, excerpted here.

Lent 2012: Day 5

the immense power of kindness in bringing out the good points of the characters of others

When I can lift myself above my wounded ego — “What?! How dare you be cruel or disrespectful to me, who is only trying to help you get an education!” — and respond thoughtfully and kindly, a change sometimes occurs, a softening, a reflective moment of calm.

A kind word or tone can transform conflicts into positive experiences. A simple kindness of offering to help a kid by holding books while he rummages through his locker can bring a smile where once there was anger.

Even if all is well in the student’s life at the moment, an act of kindness can echo into the future. Relationships are like bank accounts: we can make deposits through kindness that will give us a buffer against emotionally stressful withdrawals.

The quoted excerpt is from Father Frederick Faber’s Spiritual Conferences, excerpted here.

Lent 2012: Day 4

Probably the majority of repentances have begun in the reception of acts of kindness, which, if not unexpected, touched men by the sense of their being so undeserved.

Reading Faber, I keep returning to thoughts of school and interactions with students. And I can’t deny that there are times, based on behavior of various students, that I find myself thinking that this or that student doesn’t deserve kindness. When someone is disrupting others, making it difficult to focus on the task at hand, focusing all her energies on getting everyone’s attention, she is attempting to take opportunities away from others. It’s a myth to think that students today aren’t interested in learning — the vast majority are, keenly so. But it only takes two or three in a classroom to derail the whole process, and an incorrigible student soon draws the ire of other students and the teacher.

It is precisely at those moments that I most decidedly don’t feel like being kind. It is in those situations that the temptation to cruelty is most acute. Responses come to mind that are so ineffably and cruelly inappropriate but at the same time seem so perfect. Yet a kind word can sometimes calm the whole situation, while cruelty will only debase everyone in the room. It’s the easy way out, which is why kindness can be so difficult.

The quoted excerpt is from Father Frederick Faber’s Spiritual Conferences, excerpted here.

Lent 2012: Day 3

Reading

Such is kindness. Now let us consider its office in the world, in order that we may get a clearer idea of itself. It makes life more endurable. The burden of life presses heavily upon multitudes of the children of men. It is a yoke, very often of such a peculiar nature that familiarity, instead of practically lightening it, makes it harder to bear. Perseverance is the hand of time pressing the yoke down upon our galled shoulders with all its might. There are many men to whom life is always approaching the unbearable. It stops only just short of it. We expect it to transgress every moment. But, without having recourse to these extreme cases, sin alone is sufficient to make life intolerable to a virtuous man. Actual sin is not essential to this. The possibility of sinning, the danger of sinning, the facility of sinning, the temptation to sin, the example of so much sin around us, and, above all, the sinful unworthiness of men much better than ourselves, these are sufficient to make life drain us to the last dress of our endurance. In all these cases it is the office of kindness to make life more bearable; and if its success in its office is often only partial, some amount of success is at least invariable.

It is true that we make ourselves more unhappy than other people make us. No slight portion of this self-inflicted unhappiness arises from our sense of justice being so continually wounded by the events of life, while the incessant friction of the world never allows the wound to heal. There are some men whose practical talents are completely swamped by the keenness of their sense of injustice. They go through life as failures, because the pressure of injustice upon themselves, or the sight of its pressing upon others, has unmanned them. If they begin a line of action, they cannot go through with it. They are perpetually shying, like a mettlesome horse, at the objects by the roadside. They had much in them; but they have died without anything coming of them. Kindness steps forward to remedy this evil also. Each solitary kind action that is done, the whole world over, is working briskly in its own sphere to restore the balance between right and wrong. The more kindness there is on the earth at any given moment, the greater is the tendency of the balance between right and wrong to correct itself, and remain in equilibrium. Nay, this is short of the truth. Kindness allies itself with right to invade the wrong, and beat it off the earth. Justice is necessarily an aggressive virtue, and kindness is the amiability of justice.

Thoughts

The burden of life presses heavily upon multitudes of the children of men and very often, we are the ones adding additional weight to that load.

No slight portion of this self-inflicted unhappiness arises from our sense of justice being so continually wounded by the events of life. We see this daily in the classroom, where twenty-some fourteen-year-old sense of justice collide, often enough with the authority figure. “Everyone else is talking!” proclaims a frustrated young man when called down. We see this daily on the road, and often enough, participate in the injustice, when someone cuts another off or fails to accelerate quickly enough to please us. We feel this when we find that our tax return is not quite what we expected, not quite what seems fair. And all of these injustices are the extent to which the vast majority of us in the developed world ever experience. Yet these are bearable burdens. There are many men to whom life is always approaching the unbearable.

Each solitary kind action that is done, the whole world over, is working briskly in its own sphere to restore the balance between right and wrong. Perhaps this is the ultimate human answer to the problem of evil: as authors of evil, we can also be creators of kindness, and the latter cancels out the former.

Lent 2012: Day 2

Reading

We must first ask ourselves what kindness is. Words, which we are using constantly, soon cease to have much distinct meaning in our minds. They become symbols and figures rather than words, and we content ourselves with the general impression they make upon us. Now let us be a little particular about kindness, and describe it as accurately as we can. Kindness is the overflowing of self upon others. We put others in the place of self. We treat them as we should wish to be treated ourselves. We change places with them. For the time self is another, and others are self. Our self-love takes the shape of complacence in unselfishness. We cannot speak of the virtues without thinking of God. What would the overflow of self upon others be in Him, the Ever-blessed and Eternal? It was the act of creation. Creation was divine kindness. From it as from a fountain, flow the possibilities, the powers, the blessings of all created kindness. This is an honorable genealogy for kindness. Then, again, kindness is the coming to the rescue of others, when they need it and it is in our power to supply what they need; and this is the work of the Attributes of God towards His creatures, His omnipotence is for ever making up our deficiency of power. His justice is continually correcting our erroneous judgments. His mercy is always consoling our fellow-creatures under our hardheartedness. His truth is perpetually hindering the consequences of our falsehood. His omniscience makes our ignorance succeed as if it were knowledge. His perfections are incessantly coming to the rescue of our imperfections. This is the definition of Providence; and kindness is our imitation of this divine action.

Moreover kindness is also like divine grace; for it gives men something which neither self nor nature can give them. What it gives them, is something of which they are in want, or something which only another person can give, such as consolation; and besides this, the manner in which this is given is a true gift itself, better far than the thing given: and what is all this but an allegory of grace? Kindness adds sweetness to everything. It is kindness which makes life’s capabilities blossom, and paints them with their cheering hues, and endows them with their invigorating fragrance. Whether it waits on its superiors, or ministers to its inferiors, or disports itself with its equals, its work is marked by a prodigality which the strictest discretion cannot blame. It does unnecessary work, which when done, looks the most necessary work that could be. If it goes to soothe a sorrow, it does more than soothe it. If it relieves a want, it cannot do so without doing more than relieve it. Its manner is something extra, and is the choice thing in the bargain. Even when it is economical in what it gives, it is not economical of the gracefulness with which it gives it. But what is all this like, except the exuberance of the divine government? See how, turn which way we will, kindness is entangled with the thought of God! Last of all, the secret impulse out of which kindness acts is an instinct which is the noblest part of ourselves, the most undoubted remnant of the image of God, which was given us at the first. We must therefore never think of kindness as being a common growth of our nature, common in the sense of being of little value. It is the nobility of man. In all its modifications it reflects a heavenly type. It runs up into eternal mysteries. It is a divine thing rather than a human one, and it is human because it springs from the soul of man just at the point where the divine image was graven deepest.

Response

Ask me some time ago — two or so years — about God and my reply would have quickly turned to the problem of evil and the problems it creates for any conception of God. The existence of consciously, conscientiously willed evil — such as the Holocaust, the abuse of a child, the torture of individual, the slaughter of innocence — presents certain difficulties for the believer. “How can such evil exist in a world with an omniscient, omnipotent, perfectly benevolent being? Either this being is not omniscient and simply doesn’t know about the evil, or is not omnipotent and unable to prevent it, or is not completely benevolent and unwilling to stop it. In any case, then, this being might be many things, but it is certainly not God as we commonly think of the term.” There are various philosophical ways to wiggle out of this, some more satisfying than others, but more difficult in some ways than the problem of evil is the problem of good, the problem of kindness.

In a strictly material, evolutionary sense, what meaning does altruism hold? Whence comes pity, or even more confounding, empathy? One can make a convincing argument for the material logic of kindness among one’s own family or even clan: it’s a question of preserving one’s genetic line. But why with comparative strangers?

Theism offers an explanation:Â the secret impulse out of which kindness acts is an instinct which is the noblest part of ourselves, the most undoubted remnant of the image of God, which was given us at the first.

The reading is from Father Frederick Faber’s Spiritual Conferences, excerpted here.

Lent 2012: Day 1

Reading

The weakness of man, and the way in which he is at the mercy of external accidents in the world, has always been a favorite topic with the moralists. They have expatiated upon it with so much amplitude of rhetorical exaggeration, that it has at last produced in our minds a sense of unreality, against which we rebel. Man is no doubt very weak. He can only be passive in a thunderstorm, or run in an earthquake. The odds are against him when he is managing his ship in a hurricane, or when pestilence is raging in the house where he lives. Heat and cold, drought and rain, are his masters. He is weaker than an elephant, and subordinate to the east wind. This is all very true. Nevertheless man has considerable powers, considerable enough to leave him, as proprietor of this planet, in possession of at least as much comfortable jurisdiction, as most landed proprietors have in a free country. He has one power in particular, which is not sufficiently dwelt on, and with which we will at present occupy ourselves. It is the power of making the world happy, or at least of so greatly diminishing the amount of unhappiness in it, as to make it quite a different world from what it is at present. This power is called kindness. The worst kinds of unhappiness, as well as the greatest amount of it, come from our conduct to each other. If our conduct therefore were under the control of kindness, it would be nearly the opposite of what it is, and so the state of the world would be almost reversed. We are for the most part unhappy, because the world is an unkind world. But the world is only unkind for the lack of kindness in us units who compose it. Now if all this is but so much as half true, it is plainly worth our while to take some trouble to gain clear and definite notions of kindness. We practice more easily what we already know clearly.

The weakness of man, and the way in which he is at the mercy of external accidents in the world, has always been a favorite topic with the moralists. They have expatiated upon it with so much amplitude of rhetorical exaggeration, that it has at last produced in our minds a sense of unreality, against which we rebel. Man is no doubt very weak. He can only be passive in a thunderstorm, or run in an earthquake. The odds are against him when he is managing his ship in a hurricane, or when pestilence is raging in the house where he lives. Heat and cold, drought and rain, are his masters. He is weaker than an elephant, and subordinate to the east wind. This is all very true. Nevertheless man has considerable powers, considerable enough to leave him, as proprietor of this planet, in possession of at least as much comfortable jurisdiction, as most landed proprietors have in a free country. He has one power in particular, which is not sufficiently dwelt on, and with which we will at present occupy ourselves. It is the power of making the world happy, or at least of so greatly diminishing the amount of unhappiness in it, as to make it quite a different world from what it is at present. This power is called kindness. The worst kinds of unhappiness, as well as the greatest amount of it, come from our conduct to each other. If our conduct therefore were under the control of kindness, it would be nearly the opposite of what it is, and so the state of the world would be almost reversed. We are for the most part unhappy, because the world is an unkind world. But the world is only unkind for the lack of kindness in us units who compose it. Now if all this is but so much as half true, it is plainly worth our while to take some trouble to gain clear and definite notions of kindness. We practice more easily what we already know clearly.

Thoughts

Being a teacher, I am able to exercise this one power of humanity on a daily basis. Children come to me from a range of different environments and daily events. Some come hungry; others come angry. Some come feeling betrayed; others come feeling abandoned. This hunger, anger, betrayal, and abandonment — and the hundred and one other emotions and experiences–can be taken literally, figuratively, or both. This, in a sense, unites us: we all feel hungry, angry, betrayed, and abandoned at some point or another in our lives. And all this stems from the unkindness of the world that we experience every day, with some of us experiencing more of it than others.

So I have to ask myself: when these kids come in grouchy, disrespectful, high-strung, or any other of a million little things that might or might not irritate or anger me, how do I react? Not knowing why this boy is scowling and daring me to say anything at all to him, why this girl is instantly angered by the smallest thing, how can I do anything but exert the one power that I as a human possess? The world is only unkind for the lack of kindness in us units who compose it. I can add to that, or take away from it.

Yet there’s more to it than that. My actions are the best teacher for these kids. We practice more easily what we already know clearly. If I show it clearly, perhaps they will know it clearly; if they know it clearly, perhaps they will begin to show it clearly.

The reading is from Father Frederick Faber’s Spiritual Conferences, excerpted here.

Surrender

“Lent is when you give up something that you like,” L explains, sharing what she learned during the Children’s Liturgy at Mass this Sunday. “Pretend you didn’t like dark chocolate,” she elucidates, smiling, as if it were possible for the Girl to claim with a straight face that she doesn’t like dark chocolate. “You couldn’t give that up because that would be nonsense.”

Indeed.

I tell L that it’s not enough just to give up something you like. “If it’s something like but don’t use often, then what are you really giving up?” I ask. Which is why dark chocolate is not an option for a meaningful Lenten sacrifice for me. At one point, it would have been cigars and libation: indeed, that’s what I did last year. But I’ve all but sworn off cigars, limiting myself to one a month, and libation quickly followed suit.

As I finish explaining this, L quickly replies that she’s going to give up making messes for Lent. K calls out from the kitchen, “I’m giving up cooking!”

Our actual decisions are somewhat less silly:

- The Girl has given up two of her four Barbies and a favorite book.

- I’ve sworn off online chess playing, deciding to replace it with a Lenten reading schedule and a bit more thinking out loud here about what I’m reading.

- K, having given up so much for the baby, is giving up nothing in addition. Very wise.

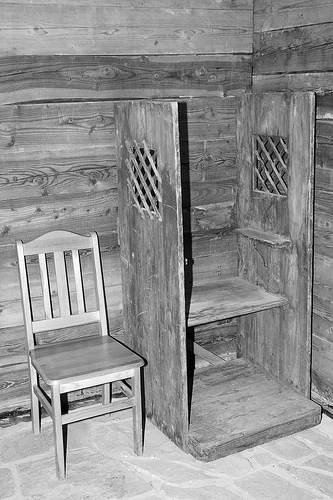

#26 — Confession

Confession is perhaps one of the most inexplicable elements of Catholicism for non-Catholics. The common view is, “Why should I confess to a priest instead of confessing directly to God?”

It’s not my intent to discuss whether or not confession is, as Protestants would press, strictly Biblical. In that end, I’ll mention only the basics: The Catholic Church bases confession primarily on two passages. The first is John 20:19-23:

On the evening of that first day of the week, when the disciples were together, with the doors locked for fear of the Jewish leaders, Jesus came and stood among them and said, “Peace be with you!” After he said this, he showed them his hands and side. The disciples were overjoyed when they saw the Lord.

Again Jesus said, “Peace be with you! As the Father has sent me, I am sending you.” And with that he breathed on them and said, “Receive the Holy Spirit. If you forgive anyone’s sins, their sins are forgiven; if you do not forgive them, they are not forgiven.”

The other is the renaming of Simon in Matthew 16:17-19:

Jesus replied, “Blessed are you, Simon son of Jonah, for this was not revealed to you by flesh and blood, but by my Father in heaven.And I tell you that you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not overcome it.I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven; whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.”

One can argue about the interpretation of those passages, but even a cursory reading seems to indicate that the Catholic Church is on fairly solid ground, Scripturally speaking.

Still, I’m not interested in proving anything; I’m fascinated simply by the act. So many non-Catholics seem to find it appalling, but it seems to be a healthy way to deal with guilt — provided one is a believer. As I understand it, confession is not merely a matter of saying, “I’ve done this,” and the priest responding, “Now go do this.” If one is fortunate enough to get a good confessor, it seems like it would be more of a dialogue than a diatribe. One would not be going to confession over a matter one didn’t think was a character flaw. The act of confessing — truly confessing, and not just going through the motions — indicates that one wants to change, and discussing how to make those changes seems healthy.

It is, after all, what psychiatrists do.

#25 — Mysticism

Mysticism is one of the many elements of religion that seem to exist in every faith. It is present in monotheistic religions and Eastern religions alike: there are Christian mystics, Muslim mystics, Sikh, Jain, Buddhist, and Hindu mystics.

The Catholic Encyclopedia defines mysticism as “either a religious tendency and desire of the human soul towards an intimate union with the Divinity, or a system growing out of such a tendency and desire.” In that sense, it’s easy to see why mysticism is a religious universal.

Yet by and large, there are no Protestant mystics. Indeed, part of the Reformation was a rejection of all that’s non-Biblical, and so reformers viewed mysticism skeptically.

Catholic history, though, is filled with mystical visions and experiences. As with so many other aspects of Catholicism, it seems to me to be something admirable regardless of one’s personal take on it. To so vehemently defend the importance of something the rest of the “modern” world explains away is the height of either or trust. Or perhaps a mix of the two.

It stands to reason that Catholics would be more included to accept mysticism than Protestants: at the heart of the Catholic faith is mystery. “Let us proclaim the mystery of faith,” says the priest at the end of the Eucharistic prayer, to which English speaking parishioners make one of four responses:

- Christ has died, Christ is risen, Christ will come again.

- Dying you destroyed our death, rising you restored our life. Lord Jesus, come in glory.

- When we eat this bread and drink this cup, we proclaim your death, Lord Jesus, until you come in glory.

- Lord, by your cross and resurrection, you have set us free. You are the Saviour of the world.

The mystery the priest speaks of is not a Mystery Machine type of mystery. In this sense, mystery simply means something we cannot fully grasp through reason.

#23 — Reasonable Redux

For example, if one were to set a Lenten goal and were not be able to make it despite intentions to the contrary, the Church is wise enough to realize that in many things, the intentions are as important, if not more important, than the actual action. And that is why I can write this exhausted post and still feel I’m keeping my Lenten promise.

#22 — Visual

Any Catholic space is a feast for the eyes. There’s so much to look at that it’s almost overwhelming: stained glass, statues, icons, frescoes, murals, carvings — a traditional (i.e., old, European) Catholic church is filled with visual stimuli.

Even the simplest wooden church is filled with details that drawn individuals to get a closer look. And entering a great cathedral like Notre Dame of Strassbourg is an overwhelming visual experience.

Yet it’s not just what individuals see now that sets apart Catholicism; there’s a history of visions throughout the Church: corporal visions, imaginative visions, intellectual visions, visions of saints, visions of demons, and probably, at least once, visions of visions. They’ve happened all over the world, and they continue occurring today, so there’s something in Catholicism that either encourages this or encourages believers by causing this. It’s either wish fulfillment or genuine experience — or a mixture of both.

Now I’m not going to suggest that this impresses me. I don’t know whether these seers actually had an experience or whether it was all suggestion and will. That’s not something I can decide. However, I find it striking how very important vision is in the Catholic faith, especially compared to other faiths. Seeing is not believing, but it helps, and Catholicism realizes that and makes use of it.

#17 — Universality

“Catholic” means “universal,” and that is an apt description.

Fr. Dwight Longenecker, a local priest with a reputation that extends well beyond the region, explains it better than I could:

We had confirmation at Our Lady of the Rosary parish on Tuesday. What I love about the Catholic Church is her universality. In the congregation were Vietnamese, Palestinians, Nigerians, Poles, Philippinos, Mexicans, El Salvadoreans, French, German and more…why there were even a few converts there too.

We were all united in one church, one faith, one baptism. The bishop was there and our priesthood was united with his and with the gift of Our Lord to the Apostles.

In addition to the ethnic mix there was the socio-economic mix–executives from Michelin and BMW mixing with Mexican immigrants and everyone in between. (Source)

Another measure of the universality of the faith is the number of languages used to celebrate Mass at a given church. The church we attend has Mass in English, Spanish, and, once a month, Polish. Other, larger cities certainly have even more variety.

#11 — The Tactile Church

I am aware of the tactile sensations of my body in a Catholic church in a way that I never was in any Protestant church.

Part of this goes back to my first experiences with Catholicism in Poland. Going to a Mass with someone — most often, K — I knew would be painful. It was not that I hated the liturgy or thought it a waste of time. I knew it would be physically painful: there was very, very rarely free space in any pew, so we spent the Mass standing or kneeling. On a stone floor, this was always tough on my already-injured knees and prematurely-paining back. It added an ascetic dimension to Mass.

Yet mortification of the flesh is not the only — or most common — sense that I think of Catholicism as tactile. Anointing, genuflecting, crossing oneself, baptizing, and kneeling all heighten, in one for or another, one’s awareness of the body. As a non-Catholic, I often feel the distinctness of my lack of action when the individual before me genuflects before entering the row of pews and I don’t, or when my neighbor crosses herself along with everyone else and I don’t.

I wonder if that would change were I to follow suit…

#10 — Smells

Walking into an ancient Catholic church can be overwhelming to the senses: the magnificence of the architecture, the completeness of the silence punctuated by echoing footsteps, the cool damp air on one’s skin. Yet for first time visitors, the most distinctive surprise is the odors of a church.

A mix of old incense, wood, dampness, stone, cleaning solutions, humanity, and a thousand other mysterious odors almost seduce me from the moment I first entered an historic Catholic church. The stone has been gathering the breath of believers for ages, and the natural dampness of the air activates these strong, earthy odors in the walls and floors. Incense, one of the most noticeable Catholic/Orthodox distinctive practices, lingers from Mass to Mass, mixing with the stones and damp to form a redolence that can only be described as the smell of tradition.