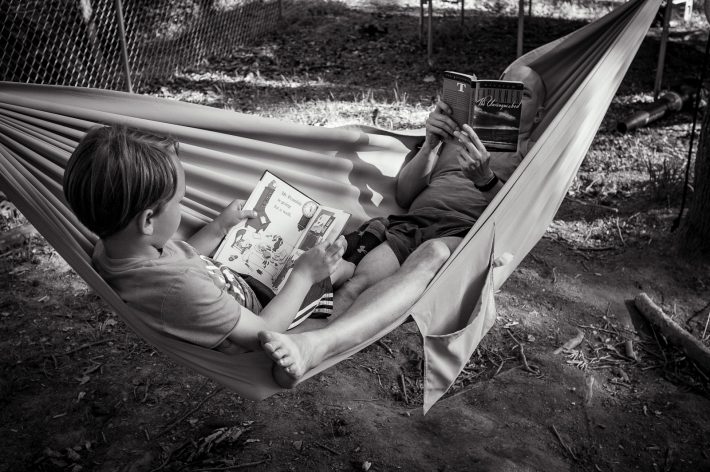

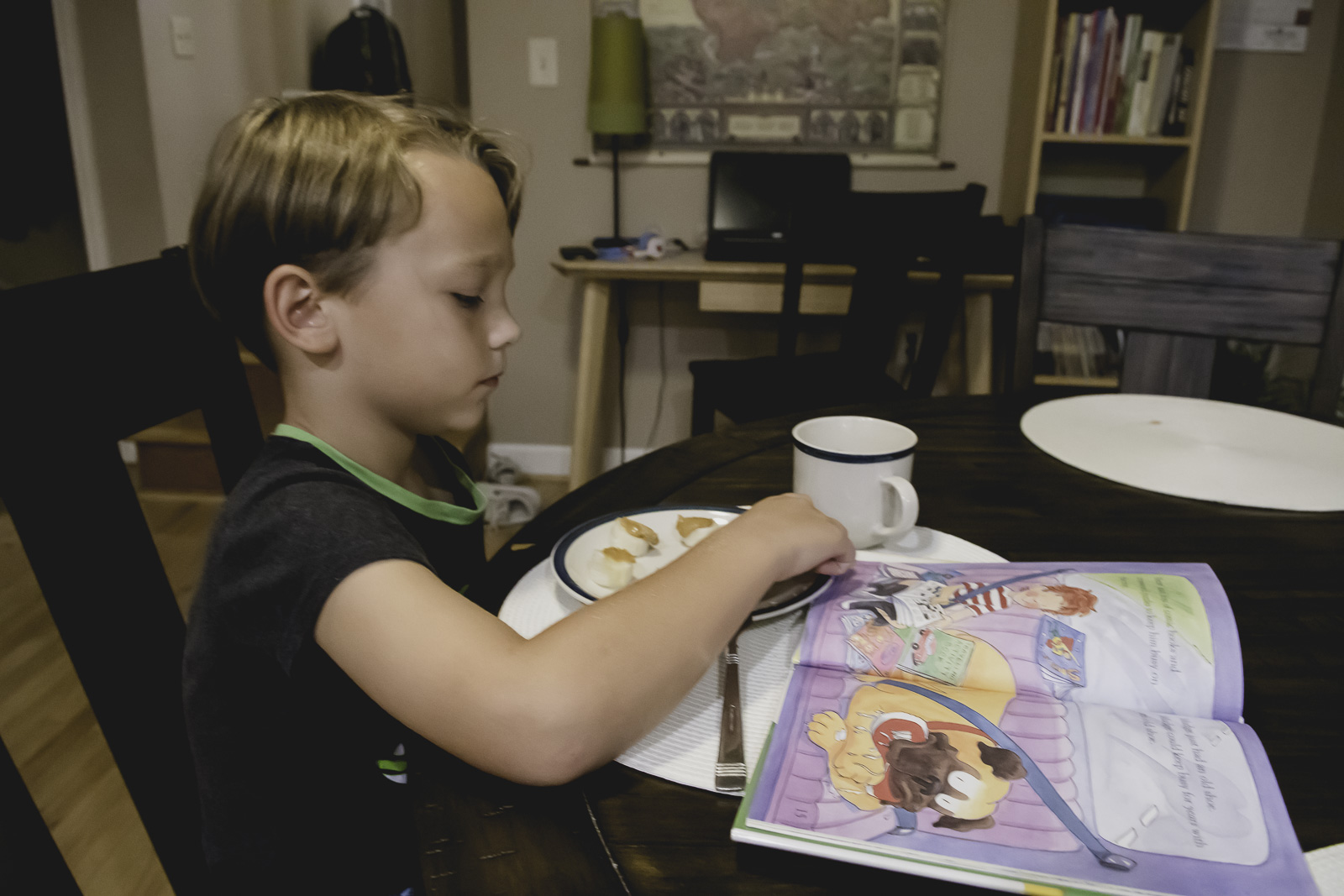

We try to get the Boy to read a little every night. Tonight we worked on L’s old book about spiders. I found the place we’d left off, but the Boy insisted that he’d finished with K last night.

“Well, it doesn’t hurt to read it again,” I said. It might have sounded like I was just being lazy, but being able to read a tricky passage fluently will build his confidence. We learn by repetition, especially recognition of new words.

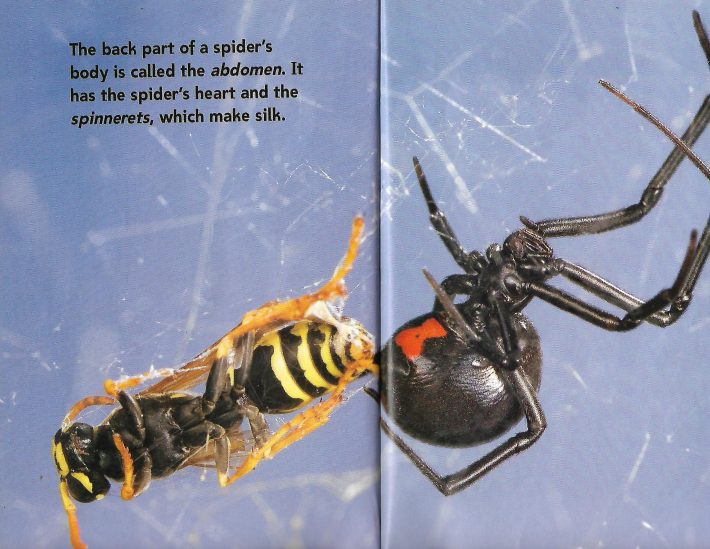

“The back part of a spider’s body is called the abdomen,” he began.

“Wow — you read that tough word like a pro,” I added.

“What word?”

“Abdomen.”

He sighed. “Daddy, I recognized the word.”

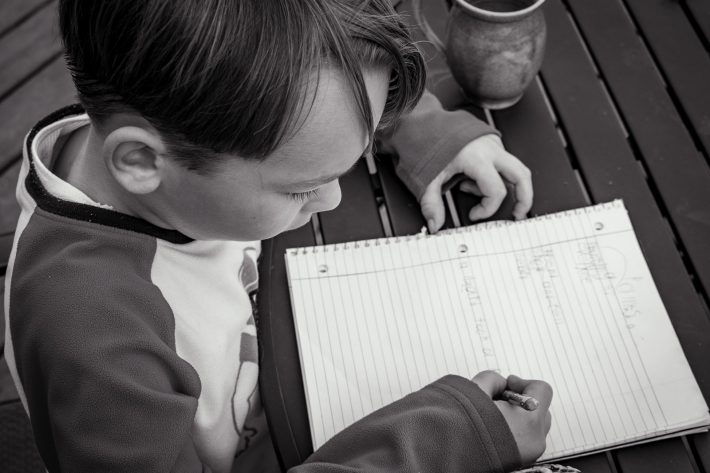

“I know. And that’s a long word to know. How many letters?”

He counted: “Seven.”

“You recognized a seven letter word!”

“No, wait,” he said, counting hopefully again. “No, just seven.”

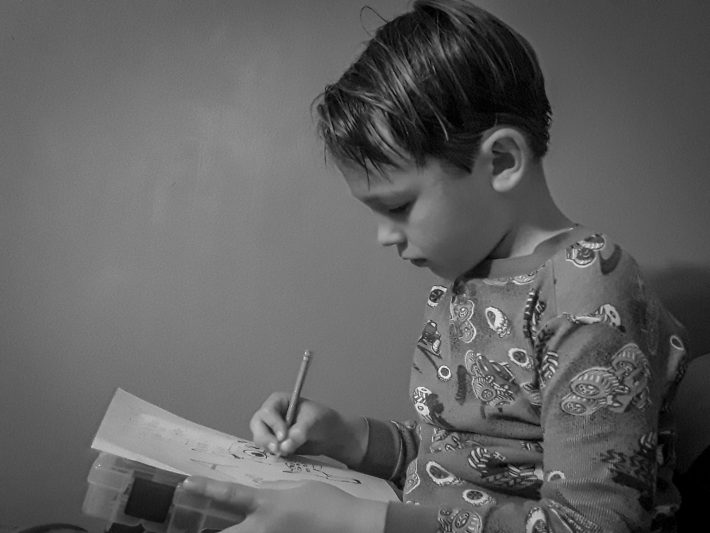

He continued, stumbling a bit: “It has the spider’s hear — hear?”

“Heart,” I helped.

“Heart and the spinnerets, which make silk,” he continued.

“Spinnerets?!” I gasped. “Are you kidding? You read that like a pro as well!”

“But daddy, I stumbled over a” and he paused to count. “A five-letter word.” He often stumbles over words, words that sometimes surprise me. And he recognizes and reads fluently words that sometimes surprise me. It’s part of learning to read.

“That’s okay,” I reassured. “You stumbled over that word, but you nailed ‘spinnerets.'”‘

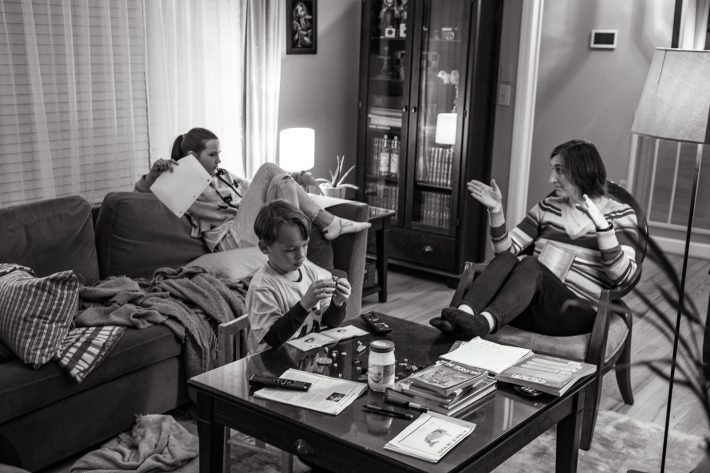

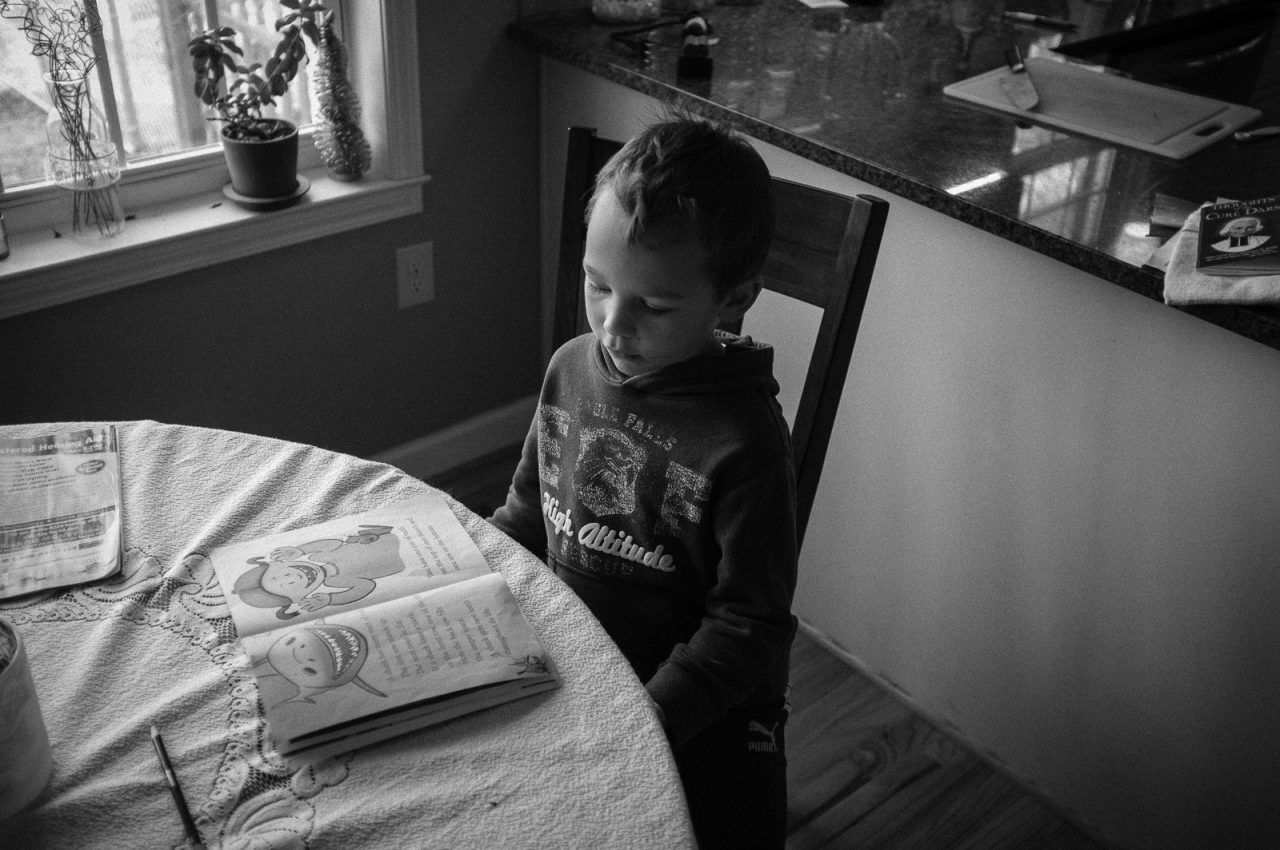

Many of my students over the years have face similar struggles, and struggling readers are not confident readers. I’ve sat with kids who were reading, asked them to read aloud, and heard difficult passages come out like this: “It has the spider’s hea hear — whatever — and the spin spin — I don’t know — which make the silk.” If that’s what’s going on in their head as they read silently, and there’s no reason to think it wouldn’t be, it’s no wonder they don’t feel confident with reading: the struggle produces nothing but a confusing text. And they’re likely to anticipate all this: before they begin reading, they’ve convinced themselves that they won’t understand it. And all of this builds and calcifies into not a mere reluctance to reading but a positive aversion to it.

Confidence eliminates those “whatevers” and “I-don’t-knows.” And so I have the Boy read books a second, third, and fourth time.

“But I already know this book,” he complains.

“I know — that’s the point,” I think.