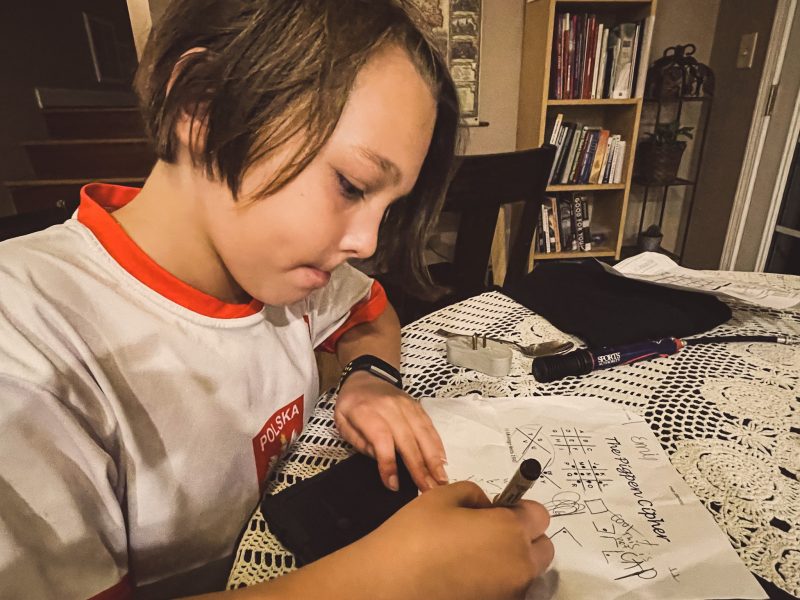

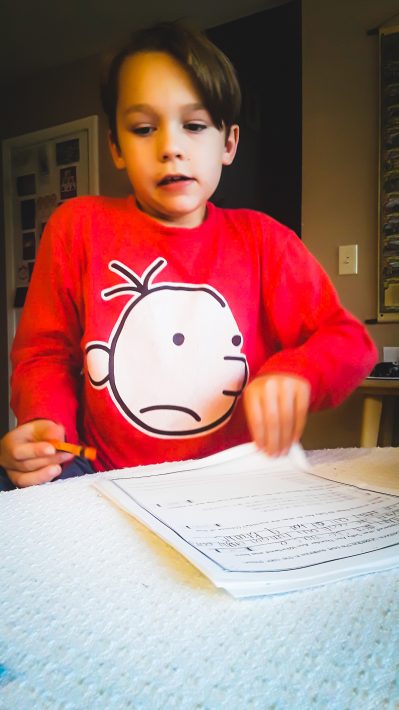

The Boy’s girlfriend informed him that her dad let her drive the car (with him in it, of course) from their neighborhood’s clubhouse to their home.

“When can I go driving?” he pestered me. “After all, I’m the one who’s obsessed with cars. R doesn’t even care about cars, and she’s already gotten to drive!”

So this evening, we went to an enormous abandoned (virtually) building’s equally enormous parking lot to give him a chance to drive. He never applied the accelerator: it was nerve wracking enough just letting the car pull us along — a surprise to the Boy.

His verdict: “This is better than any video game!”