Nearly twenty-five years ago, I had my career track all planned: a Ph.D. from Boston University in the philosophy of religion followed by a lifetime of teaching (hopefully at a small college where I could work in both the philosophy and religion departments) and writing. I was in a seminar about Friedrich Schleiermacher’s On Religion: Speeches to Its Cultural Despisers, and I couldn’t get out of my mind the homeless man who was bedding down in front of the building where we were all sitting, talking about a 200+ year old treatise about religion.

It all seemed so impractical, so useless: I dropped out after that semester.

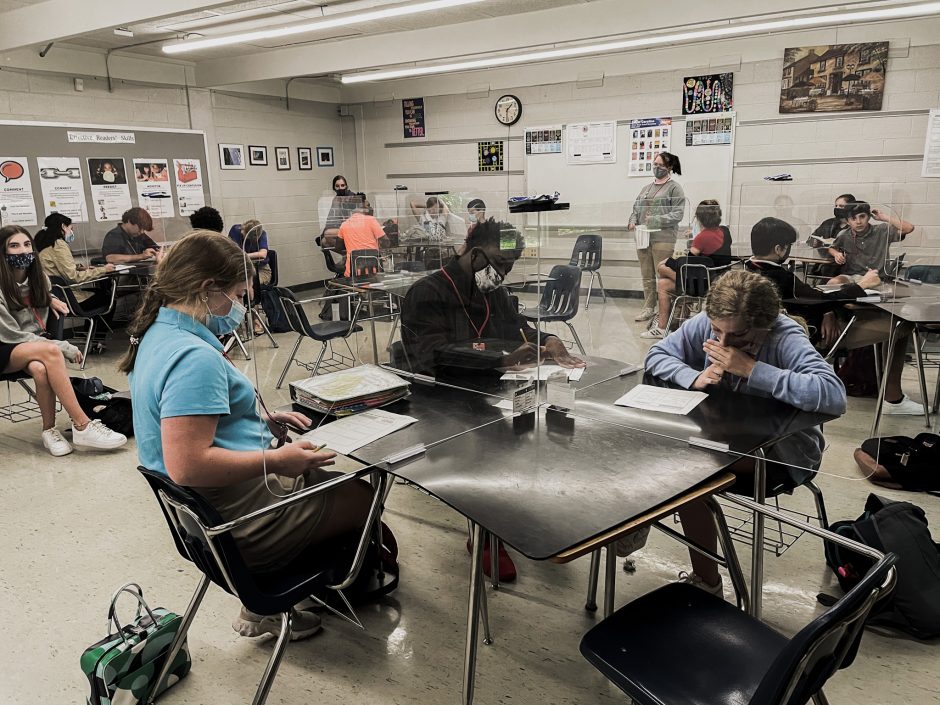

I’m still pleased with that decision because my work now is so very practical: I teach kids how to read and write better. And as for my writing bug, there’s this site.

A few weeks ago, though, I thought I’d look up an acquaintance from my undergraduate years who was going to do graduate work in philosophy as well. I found him: he completed his doctorate, and now he teaches philosophy at a university and writes.

Reading an interview with him, I got a glimpse into what my life would be like if I’d continued at B.U. One thing I’d be doing is writing jargon-filled nonsense of little practical value.

Modern philosophers can’t seem to write without stuffing as much falsely impressive jargon into every inch of every sentence. Instead of asking an acquaintance, “Would you like to see a movie with me?” they say things like,

Ah, my dear interlocutor, I extend to thee an invitation to partake in a cinematic sojourn, wherein we shall immerse ourselves in the ineffable tapestry of visual narratives. Let us engage in a dialectical exploration of the celluloid realm, dissecting the ontological nuances and epistemological quandaries presented therein. As we traverse the cinematic landscape, let our minds intertwine in a hermeneutic dance, unraveling the semiotic layers that cloak the underlying existential motifs. Join me, and together we shall embark upon a transcendental odyssey through the silver screen, transcending the quotidian boundaries of perception. What sayest thou to this proposition?

Chat GPT in response to the prompt, “write a jargon-filled invitation to a date to the movies that a philosopher might say.”

I honestly wonder if this reliance on jargon has become second nature to them. When they live in the echo chamber of academic writing, this use of jargon likely becomes the norm.

Another similarity between all these writers is their unshakable conviction that what they’re doing is somehow brave. They speak of “opening up radically new forms of thinking and practices” and “the courage” to push “the limits and boundaries of traditional orthodox thinking so intrinsic to forms of American feminism, neo-conservatism, liberalism, religion, politics, aesthetics and so on that only serve as ideological masks behind which corporate power strangles academic and political freedom.” This is an “insurrectionist movement [that] takes a stance against this political and academic tyranny by risking freedom.” These “wonderfully intrepid” philosophers are courageously creating an “indispensable provocation to thought,”

With all this talk of intrepid risk-taking, I can’t help but ask what exactly is the chance they’re taking? What are they risking? Is someone going to imprison them for questioning the “ideological masks behind which corporate power strangles academic and political freedom”? They must be the new models of bravery in our thought-driven First World. The next time I see a firefighter rush into a burning building, I’ll think, “I haven’t seen that kind of bravery since I saw some philosophers challenging the ‘boundaries of traditional orthodox thinking so intrinsic to forms of American’ thought!” A related series of questions arise from this thought: What exactly are those boundaries? Are they walls? Are they bars? How do they restrain us? Perhaps these great thinkers realize that their contribution to society is minimal at best, and they console themselves with the thought, “Well, at least we are brave and know how to string a lot of big words together.”

Finally, what they’re writing, even discounting the overwhelming obsession with jargon, makes no practical sense at all. They speak of a “concrete and materialist commitment to that surplus of a life lived to openness and joy and not the law and security,” and in fact, there’s nothing concrete, material, or applicable about it. What would this look like? What concrete actions could these writers take that we could look at and say, “Hey, I see in those actions a “commitment to that surplus of a life lived to openness and joy and not the law and security”? How can we recognize if our ideas are “married to an identity politics looking to preserve a certain predetermined zone of ‘desire,'” and what steps could we take to file for a divorce? What are the signs that “ideological structures of power have tried to denude natural powers into a deity” and how could we then determine whether those efforts “once again limits infinity by assigning them a personality, an ethnic history”? How can we identify “the need for intellectuals to organize around the core building blocks of life, air, water, and food” and how will that help us non-intellectuals?

And most critically, how can we recognize that a given “theology tumbles kenotically, inexorably, into political economy, literature, climate science, postcoloniality, critical race theory, and nonequilibrium thermodynamics, forcing us to face the earth, sky, mortals, and gods as they are―and in all that they’re not―and only then as they might yet be”? What line in a given treatise about this revolutionary theology could we point to and say, “Here, this is theology tumbling kenotically into nonequilibrium thermodynamics”?

I seriously don’t know how anyone can take themselves seriously when they write this stuff.

The Boy loves cars. I mean loves cars. He has a sizable collection of matchbox cars (yes, that is a brand name but like Kleenex, it’s come to represent the object in general), mostly thanks to Nana and Papa, and among these cars is a garbage truck. A favorite. And that explains his interest in the following exchange.

The Boy loves cars. I mean loves cars. He has a sizable collection of matchbox cars (yes, that is a brand name but like Kleenex, it’s come to represent the object in general), mostly thanks to Nana and Papa, and among these cars is a garbage truck. A favorite. And that explains his interest in the following exchange.