Today is Holocaust Remembrance Day, when we recall all the millions of Jews who died at the hands of the Nazis, some of whom stood in line for the gas chambers at Auschwitz and Treblinka, at Chełmno, Belzec, and Sobibor. It is something unthinkable for me: why stand peacefully in line? Why not fight? Of course, it would be in vain, but why not resist? Of course in the early days, they might not have realized what was happening, for the Nazis went to great measures to hide the fact that they were about to die. Still, rumors spread as the Holocaust continued, as people escaped from camps and told their stories, and many knew what was about to happen. Still, they stood in line for showers that many of them knew were not actual showers. Perhaps they did not want to panic their children. Perhaps they wanted their last moments to be as peaceful as possible. Whatever the reason, many of them waited in line.

Tonight, I was waiting in line at Barnes and Nobles when I saw the cover of this month’s Atlantic. The cover story is an article by Jeffrey Goldberg entitled, “Is It Time for the Jews to Leave Europe?” It is an article that details the stunning rise in anti-Semitism in Europe. Goldberg writes that “France’s 475,000 Jews represent less than 1 percent of the country’s population. Yet last year, according to the French Interior Ministry, 51 percent of all racist attacks targeted Jews.”

While the article dealt with, for example, the highly nationalistic, ultra-right Nation Front of France and Greece’s openly anti-Semitic Golden Dawn, Goldberg also spends a great deal of time discussing the rise of Islamic anti-Semitism.

Finkielkraut[, a French Jew,] sees himself as an alienated man of the left. He says he loathes both radical Islamism and its most ferocious French critic, Marine Le Pen, the leader of France’s extreme right-wing–and once openly anti-Semitic–National Front party. But he has lately come to find radical Islamism to be a more immediate, even existential, threat to France than the National Front. “I don’t trust Le Pen. I think there is real violence in her,” he told me. “But she is so successful because there actually is a problem of Islam in France, and until now she has been the only one to dare say it.”

Goldberg goes on to give numbers: “Violence against Jews in Western Europe today, according to those who track it, appears to come mainly from Muslims, who in France, the epicenter of Europe’s Jewish crisis, outnumber Jews 10 to 1.”

Yet for secular, left-leaning Western Europe, there is a problem: Muslims are seen as victims just as much as Jews. Scratch that: more so: “’People don’t defend the Jews as we expected to be defended, [Finkielkraut] said. ‘It would be easier for the left to defend the Jews if the attackers were white and rightists.'” Even Goldberg seems to see the problem with Islamic anti-Semitism as a question of social injustice rather than a theological component of Islam itself when he explains that the “failure of Europe to integrate Muslim immigrants has contributed to their exploitation by anti-Semitic propagandists and by recruiters for such radical projects as the Islamic State, or ISIS.” One only has to look at imams’Â comments coming out of the Middle East to see the prevailing contemporary view of Jews in the Islamic world.

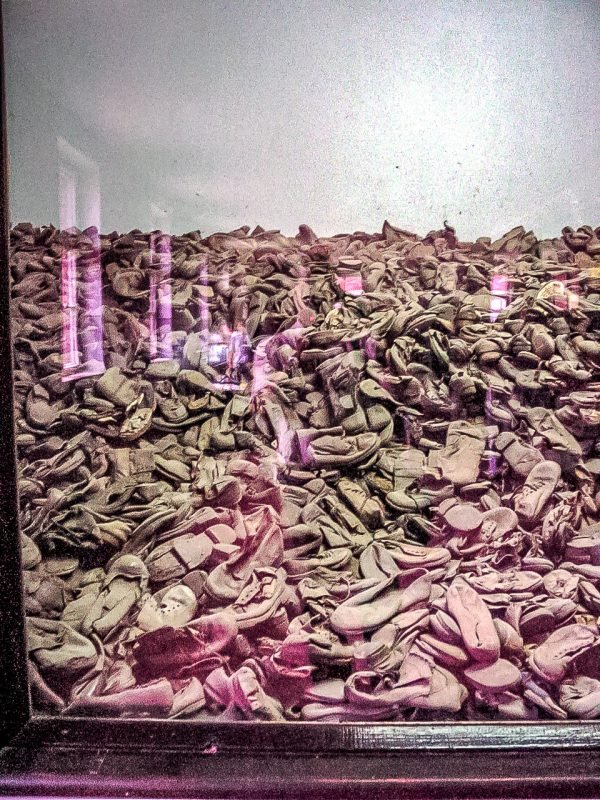

As I stood in line, though, not having read the article, I was initially taken aback: I thought for a moment it might be an extreme leftist anti-Zionist diatribe and not just one that skates close to anti-Semitism but that openly embraces it. I decided I must read it when I got home, though. I looked down at the book I was purchasing, ironically about Auschwitz, then glanced around the shop. A covered Muslim woman was approaching with her uncovered husband and son. I glanced at the book in my hand, glanced at the Muslim family, glanced at the magazine cover, and wondered at the irony of the moment.