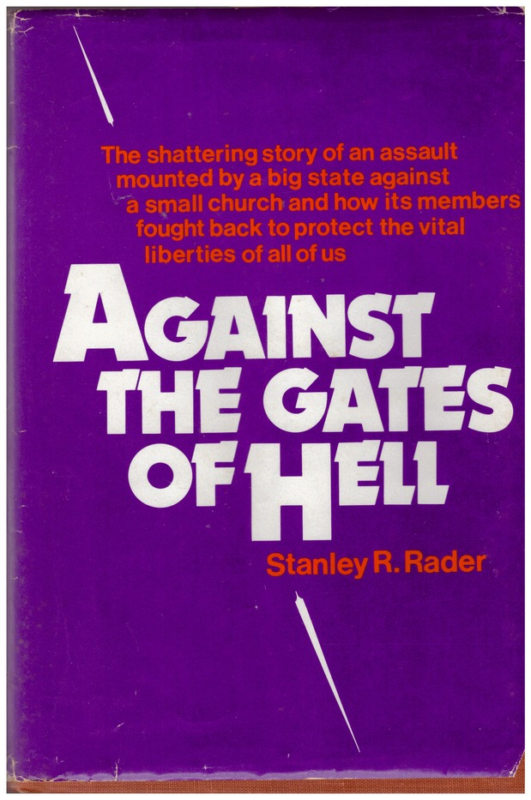

The book purports to tell the story of a church’s fight for religious liberty. Specifically, it’s supposed to be an insider’s account of the State of California’s actions against the Worldwide Church of God (WCG), legal actions that began 3 January 1979 and concluded some months afterward. The state placed the church into receivership to investigate allegations of fiscal impropriety. That, of course, fed right into the church’s prophecy that it would be persecuted in the end times, and after reading the book and doing some research, I’m not convinced the state acted wisely at all.

Still, the book is supposed to be about that legal battle, and it does cover some of that. There are a couple of chapters that are virtually hour-by-hour accounts of what happened in the first days, but quickly enough, Rader veers off and spends a great deal of the book covering other things:

- The biography of WCG founder Herbert Armstrong

- An autobiographical sketch of the author

- An account of all the traveling Armstrong and Rader did in the name of the church

- The story of the building of Ambassador Auditorium and the performers who performed there

My rough estimation is that only a third of the book (at best) is about the actual legal action. That’s too bad, because it’s in the other portions of the book that Rader loses all credibility, presenting accounts that just read like fabrications.

He writes of visiting Jordan and spending time “with Prince Mohammed, the younger brother of King Hussein.” The prince was eager to play chess with someone, and Rader’s wife Niki volunteered to play him. The prince won the first game, and as they began the second game, he admitted that it was somewhat unfair. “You see, I am the president of the Jordanian Chess Federation,” he explained.

My wife said nothing. She merely pursed her lips and then proceeded to demolish Mohammed, not only capturing his queen but also giving it back to him. The prince looked astounded and the board was set up a third time. Niki destroyed him again.

Rader explained to the astonished prince, that what his “‘wife failed to tell you was that she plays all the time’ I paused just a split second — ‘with Bobby Fischer.’ Fischer, of course, is the former world chess champion with whom Niki does play, though he beats her consistently.” Fischer was, at that time, associated with the WCG, and it’s possible that she did play some chess with him, but the anecdote feels contrived.

When writing about the initial concerts in Ambassador Auditorium, which the arts community in Los Angeles supposedly jealously resisted, he writes,

Resistance came from yet another area. When the 1975 series was announced, a rabbi, noted for his radical stance on issues, charged that the Church and the foundation were launching a grave assault on Judaism! In radio broadcasts and newspaper interviews, he urged a Jewish boycott of the series. His reasoning, as I gather it, was as follows: Jewish parents attending the concerts with their children would see a lovely campus, have their cars parked by polite, well-groomed Ambassador College students, sit in a splendid hall and view all around them other well-spoken, well-dressed students. On the way home, the parents would turn to each other and ask: “Why can’t our kids be more like that? Maybe we ought to send them to Ambassador College.” Then, of course, they would be converted. The situation may sound funny but it was serious.

Again, it seems silly. Even if this unnamed rabbi said that in mock seriousness, he was surely joking. Anyone who knows the bizarre and silly teachings of the WCG would realize that Jewish children would be at no risk of converting to a little group that suggests that proof that Britain is one of the Lost Ten Tribes is the “fact” that “Saxon” comes from a shortened version of “Isaac’s sons.” Just drop the initial letter and we have “Sacc’s sons”! (Herbert Armstrong floated this theory in his largely-plagiarized “The United States and Britain in Prohephy” book.)

A final example: Armstrong and Rader were trying to get Herbert von Karajan to conduct the inagural concert. In their conversation, they had the following exchange:

Thinking back, I can see how wildly ludicrous it all must have seemed. Here we were in Germany, talking about bringing over a great conductor and a great orchestra to play in an auditorium that wasn’t there, and blandly asking him to set a date. Yet so total was Mr.

Armstrong’s confidence, so potent his persuasiveness, and so appealing the picture we painted of the great cultural center, that von Karajan became convinced. He studied his calendar, trying to shift dates. But when he was available, the orchestra was not, and when the orchestra had time, he did not. Regretfully, he informed us that it would be impossible for him to come.

“Maestro,” I asked, “in your opinion, who is second to you in the world as a maestro?”

“There is no question,” he replied at once. “Second to me is Giulini.”

“Oh,” I said, glancing at Mr. Armstrong. “Is that right?” I had never heard of Giulini and neither, I was certain, had Mr. Armstrong.

“Absolutely,” Von Karajan was saying. “He is a great artist.”

This seems a caricature of what a “great conductor” would say. Second to me?! Perhaps von Karajan was so arrogant, but it just doesn’t seem realistic at all.

Finally, there was a conversation with Arthur Rubinstein:

Looking up, he asked Mr. Armstrong sternly: “Sir, are you a professional?” Mr. Armstrong, beaming said: “No, I’m not, but you are and you will agree after you have had a chance to play them.” He explained they were Steinways, carefully selected by him and purchased in Hamburg.

Now Rubinstein became distinctly annoyed. “Sir,” he said, “I don’t like that kind of talk from nonprofessionals.” Mr. Armstrong said he understood, but once again repeated his assertion.

With the pianist continuing to bristle, I felt it wise to change the subject. “Would you like some champagne?” I asked them. Mr. Rubinstein brusquely declined but Mr. Armstrong accepted. When the waiter began pouring Dom Perignon, Rubinstein noticed the bottle and said, “I’ll have some, thank you.” To me he said: “That is all I drink; I was afraid you might order something else.” That broke the ice somewhat and for the rest of the evening the conversation became less strained.

Mr. Rubinstein agreed to perform. A couple of days before his concert, I met him in front of the auditorium and escorted him inside. While he was enormously impressed with the grounds, the building and the foyer, the moment he stepped through the doors into the theatre – catastrophe! “This is terrible!” he exclaimed. Startled, I asked what he meant. “The carpeting, the upholstery. It’s too plush. The sound will be absorbed. It will never do! Oh, I should never have come… How could you have good music with this!”

“Maestro,” I reassured him, “I know what you think, but please believe me. The acoustics are absolutely perfect. Please don’t worry about it.” I followed him down the aisle toward the stage, trying to calm him but his agitation grew as he progressed. I could see he didn’t believe a word.

“Let me see the pianos,” he grumbled and stormed up to the stage.

He ran his Fingers over the keys and the miracle happened.

He played chords on one piano, and then literally ran to the other. For many minutes he scurried between them, playing on each, his face mirroring wonderment and pleasure. He was like a child in a candy store, going from one delight to the other and unable to make up his mind which to choose. Finally he said to me: “It’s never happened in my whole life. Never have I heard two finer pianos!”

Again, it just reads like invented braggadocio

That’s the tone of the whole book: it’s more Rader bragging about himself than anything else.