E has joined a swim team at a local pool, primarily because his three best buddies from school have joined the same team. I am naturally thrilled because competitive swimming was an important part of my life. I began swimming competitively in elementary school when I competed for the small community pool to which we belonged.

In high school, the swim team was my only athletic endeavor. I certainly would not have gone out for football or basketball, and while I ran track during my freshman year, an awful case of tendonitis made running more than a quarter of a mile excruciatingly painful: I quit after the first year. But swimming had always been kind to me, and even though I was always mildly frustrated that the swim team never got the kind of recognition that the basketball, football, or even baseball teams received, I would have continued swimming competitively even if the other swimmers and I were the only ones in the pool.

It’s not that I wanted to be seen as a jock — certainly not — but a little recognition for the amount of work we put into our sport would have been nice, I thought. We did have one occasion to bask in a little attention. It was during my junior or senior year, and the head swim coach arranged for some of the cheerleaders to come to support us. A cheerleader stood behind the starting blocks for the home swimmers and cheered us on from there. That I can’t remember whether it was my junior or senior year and that I am only partially certain they were standing behind the starting blocks to cheer us on (that just doesn’t seem right) show how relatively insignificant the event was for me, so I suppose I really didn’t care that much about that recognition.

For the most part, what I liked about swimming was its solitary nature. Except for relay events, swimming was just the swimmer in the water. Everything else seemed to dissolve into the muffled yelling of the few spectators — mainly parents, boyfriends, and girlfriends — who came out to support the team. To train or to compete, we didn’t need anything other than a body of water.

I also found that training had a certain meditative quality to it: back and forth and back and forth. One two three breath; one two three breath; one two three breath. Count the strokes in each lap. Count the breaths in each lap. Get a song going in your head and just let it run in cycles. I lost myself in swimming many times.

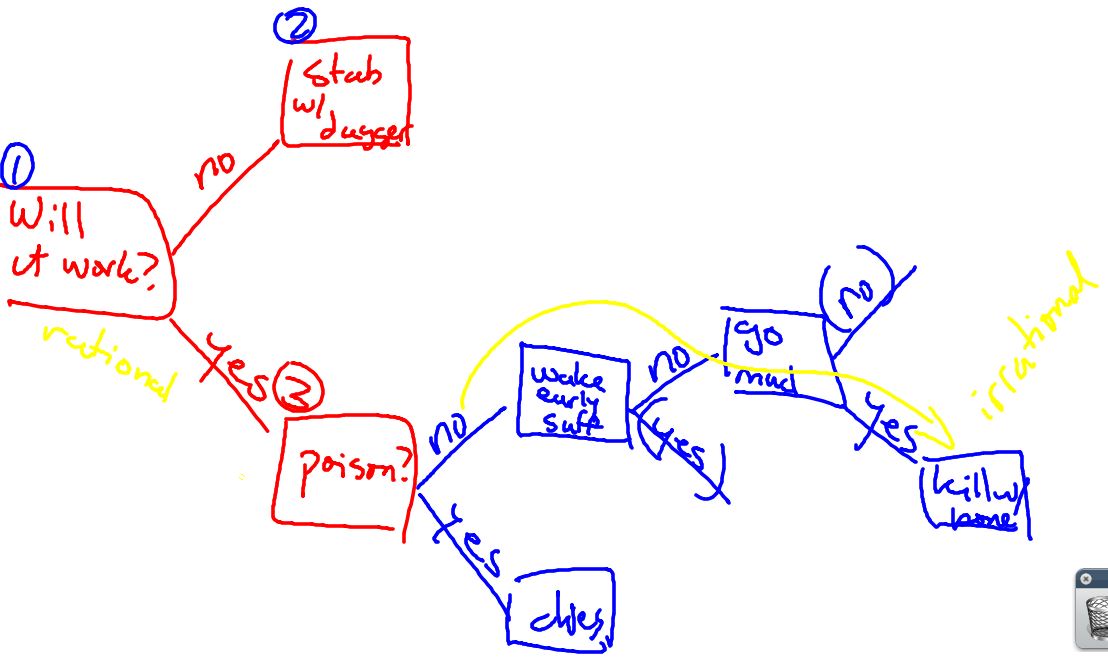

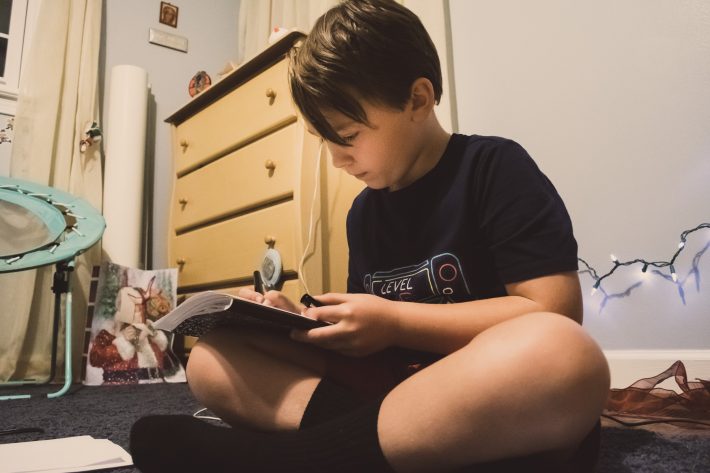

The Boy, though, is just beginning. He doesn’t have a good breathing pattern. He takes as many strokes as he can and then pulls his whole head out of the water to gulp air for a few seconds, then plunges his head back under and goes at it again. There are so many kid on the team (probably close to 30) that I doubt he’ll get much one-on-one stroke help, so I’ll have to do that as soon as school is out, and we start heading to the pool together on a regular basis.

He also stops swimming when he gets too tired. That means he swims the first length entirely. In the second length, he stops at the 15-foot red markers. After a few more lengths, he’s stopping almost midway.

“That’s when you’ve really got to push it,” I tell him. “You’ve got to ignore that pain and push through it. That is how you get stronger.”

It looks like we’ve got a summer goal cut out for us.