The tendency to spread evil beyond oneself

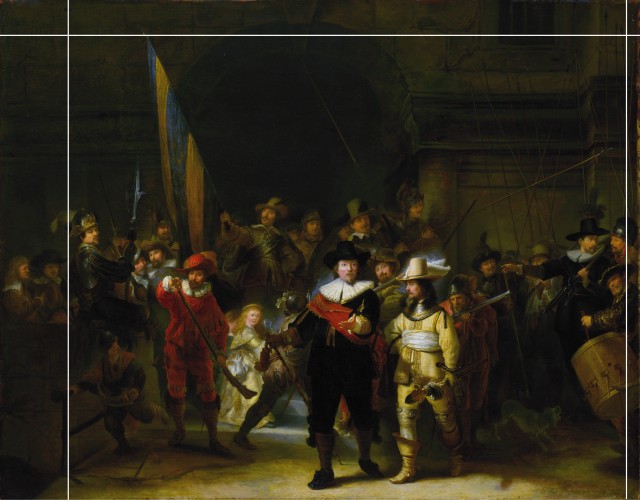

In 1715, officials transferred Rembrandt van Rijn’s The Night Watch from its location at the Kloveniersdoelen, which served as rehearsal grounds for local militia, to the Amsterdam Town Hall. These officials wanted to place the painting between two columns.

The problem was, it wouldn’t fit. So they did the obvious. They trimmed it.

Such a cavalier attitude toward art is completely unthinkable today. Modern cultures value historical works of art and go to great lengths to protect and preserve them.

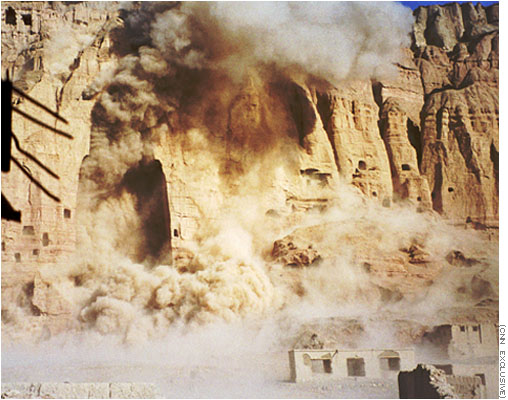

When the Taliban dynamited the Buddhas of Bamiyan in March 2001, the world decried the destruction of art of such historic value — an artifact of the world cultural heritage. Prior to the destruction, a delegation offered something of a ransom for the statues, offering to pay the Taliban not to destroy them.

I am horrified at these acts of destruction, but how often do I commit worse acts with my words? Weil writes,

The tendency to spread evil beyond oneself: I still have it! Beings and things are not sacred enough to me. May I never suely anything even though I be utterly transformed into mud. To sully nothing, even in thought. Even in my worse moments I would not destroy a Greek statue or a fresco by Giotto. Why anything else then? Why, for example, a moment in the life of a human being who could have been happy for that moment? (49)

Cutting someone down with a comment or a gesture is infinitely easier and quicker dynamiting statues or trimming canvases, and what I’m cutting when I do that — a soul — is vastly more precious than even the most beautiful creation of humanity. Why am I so willing to do this while I’d never think of destroying this or that painting, this or that sculpture? Perhaps it has to do with the ease and the lack of immediately visible consequence. An injured soul reveals itself only in the eyes, in the tone of voice, in a slumped posture, and it can skillfully hide the injuries behind a mask.

The problem of evil for many is the single most convincing argument for an atheistic stance. Dr. Peter Kreeft, of Boston College,

The problem of evil for many is the single most convincing argument for an atheistic stance. Dr. Peter Kreeft, of Boston College,