“I have a film you must see.” We were sitting in a restaurant, waiting for the next bus back to Lipnica, when Janusz told me this. “It’s a perfect film.”

“What’s it about?” I probed.

“Poland. It’s about — you just have to see it,” came the response.

For the next few weeks, whenever we met up, Janusz brought up the film.

“When are you going to come see it?” he would ask. “You have to see it. It’s a perfect film.”

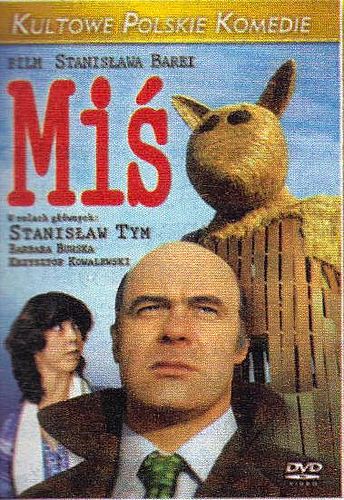

Little did I know: classic and perfect.

The first time I saw the Polish cult comedy Miś (“Teddy Bear”), I knew I’d have to see it again. I’d laughed so hard at some scenes that it was difficult to catch my breath, but I knew I’d only caught part of it. This was partially because of language — my Polish, after all, isn’t perfect — and partially because of the layers of the film.

In the years since I first watched the film, I’ve seen it countless times. Those layers are still revealing themselves with each viewing: little touches like signs in the background and repeating musical themes, things you’ll never get from one viewing. Indeed, I’ve watched it so many times now I can quote whole sections of it, and no matter one’s situation, there’s almost always a quote from Miś that is perfectly applicable.

The first shot is of a helicopter, clearly working as a flying crane. We see the wire, but it takes a moment before we see what is hanging from it.

On the ground, it becomes immediately obvious: it is a fake building with police officers milling around, part of a suprise speed trap.

As the credits roll, other officers put up two-dimensional fake buildings to create a small “village” near the road. The reasoning is simple: Polish traffic law requires drivers to slow in a teren zabudowany.

Both words have as close a thing as a cognate as just about any words in Polish: “teren” means “terrain” and “zabudowany” derives from “budowac,” which means “build.” So teren zabudowany literally means “terrain built.”

The trap, though, is incomplete without people. Other officers soon appear with variously dressed mannequins in hand. An off-screen ranking officer’s voice instructs, “Put them in a line,” and after a pause, we hear an explanation: “There must be some sign of life.”

The opening scene concludes with a soon-to-be-critical officer announcing over the radio that they are ready and that “moze zaczynac!”

“We can begin!”

What is amazing about the film, made in the very early 1980’s, is how much it mocks the Polish Communist reality and the effects of a state monopoly on everything from goods to ideas. That it made it past the censors is a minor miracle: I’ve really no idea how it could happen other than the notion that perhaps the Polish Communist party was more forgiving than Big Brother to the east. All the same, such blatant mockery?

The story, though, is simple: Ryszard Ochódzki, the director of a sports club, is trying to beat his ex-wife to London, where they have money under a joint account. Each knows the other will drain the account, and so it’s a mad race to see who can get there first. When Ochódzki’s wife, Irena, tears some pages out of his passport making it impossible for him to travel abroad, he devises one of the most complicated and convoluted schemes to get to the bank despite this seemingly insurmountable obstacle.

It’s a miraculous film, and many of the scenes resonate with my own experiences in Poland in the mid-1990’s.