In a post on social media in the group I’ve been following — people who have been participating in the “Bible in a Year” podcast, though I haven’t listened to any of it in weeks — someone posted the following:

I wish I am like Elijah who can hear God’s words.

This seems like a reasonable request. After all, if the Christian god is to be seen as a father, as he’s portrayed in the Bible, one would expect clear interactions with him. As a father myself, I try not to rely on the practice of maintaining physical distance from my children, being essentially invisible and leaving little evidence of my actual existence, while hoping we develop a good relationship through generic letters not necessarily written to them personally but to children in general. I find it’s much better to communicate to them directly, in their physical presence. This person clearly wishes her god engaged in parenting practices more like my own preferred methods and less like, well, most gods tend to prefer.

But it raises lots of questions if this god is going to maintain physical distance yet communicate audibly with his believers. I queried this believer about these concerns:

Even if it were an audible voice, how would we know it’s the voice of God and not something else, say schizophrenia? I think we pretty much discount people who say they hear God talking to them. How would we know the difference?

Her response was simple: she maintained that “somehow I think you’d know.” I naturally couldn’t let that stand: “How exactly? Especially if it were audible only to you.” She replied with the worst possible example I could imagine:

You just know! Unexplainable, but I will try. 🙂

When God spoke to Abraham. Only Abraham could hear him. Yet Abraham knew it was God.

The voices of schizophrenia is evil. Insane. The voice of God is good. Sane. The outcome of the two are complete opposites. (“How would we know the difference?—>)The results.God does not boom to us vocally from the heavens today, like we surmise Him doing back in the Bible days. Its within. *God The Holy Spirit*, whether its for God, Jesus, Mary, Joseph, a Saint, or an Angel. We instinctively know which one it is. A miracle. A mystery that can not be explained. Then faith and trust follows, because its all you have left to explain the unexplainable.

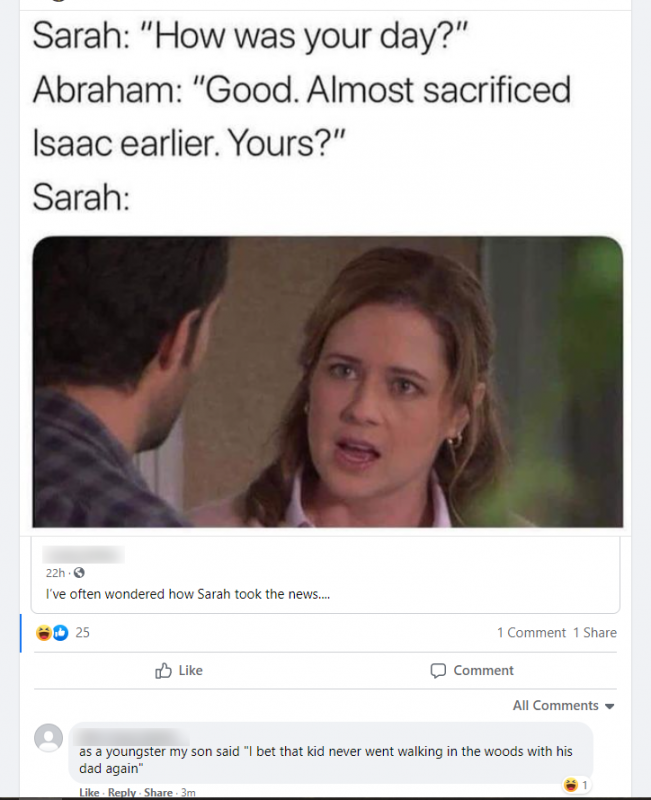

There are few stories in the Bible that I find more disturbing than the story of Abraham and Issac. I couldn’t let it stand without comment:

The voice of God told Abraham to kill his son. That sounds pretty insane. If you heard what you thought was the voice of God, would you be willing to do the same? I know I wouldn’t.

The response:

God speaks in different ways…sometimes audibly..sometimes through others…sometimes in a way only your soul recognises.

So beautiful.It’s like being in love. You just know.

“It’s like being in love.” Yes, I guess sometimes you just know — but most of the time I’ve “known,” I was wrong. I was right only once.

[G] I always know.. it comes in threes…usually through the media or through a priest during a homily.

What method did this person use to determine this? How do we know whether or not to count some event as part of those “threes”?

[G] You know. A voice you’ve never heard before, yet is some how the most familiar voice ever. The sound of pure, unconditional love. A peace and calmness, total serenity comes over you. 99% of the time God leads in ways other than a voice, and it can be difficult to decipher His will as He will not impose upon our freedom of will. However, if God wants to say something to you, there is no question, He will make Himself be known.

If you’re looking for a god, that’s exactly what you’ll find.

I don’t know why I do this…

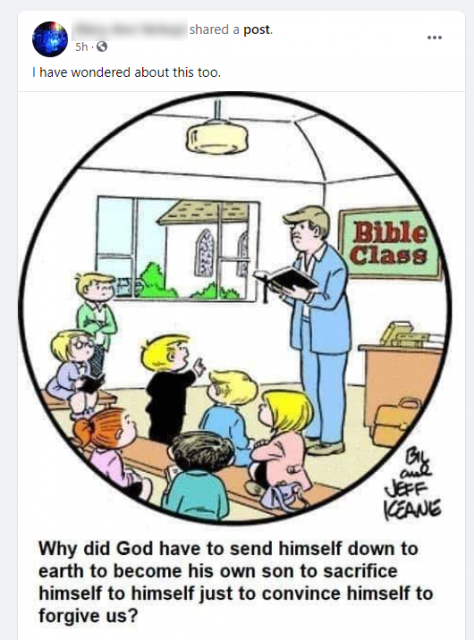

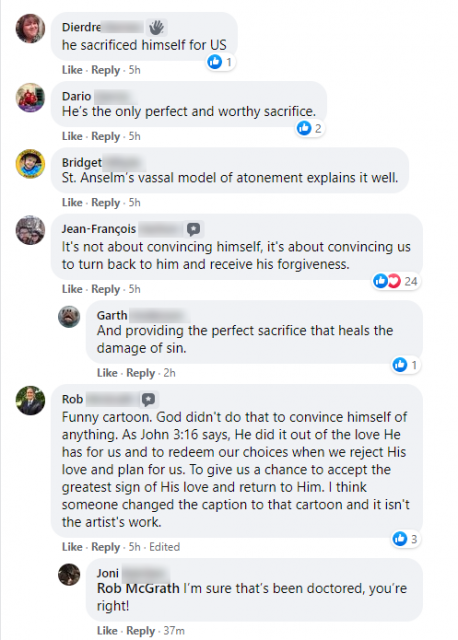

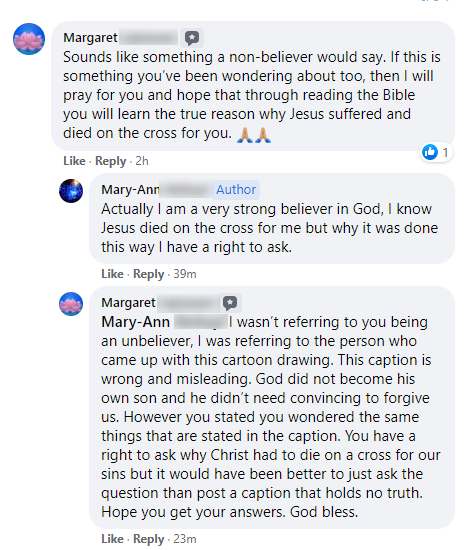

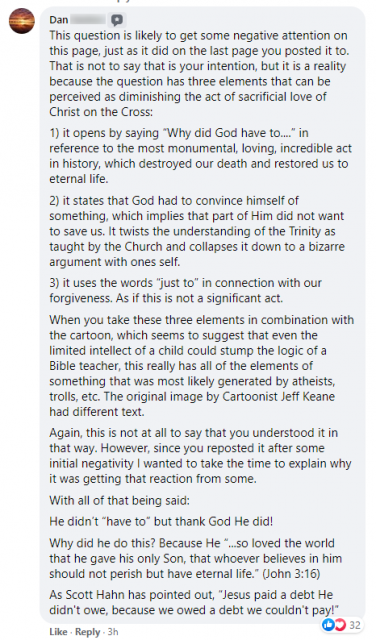

We see what we want to see. Social media offers the best example of that in the contemporary world, but sometimes, it’s not just evident in a macro-view but in individual postings.

We see what we want to see. Social media offers the best example of that in the contemporary world, but sometimes, it’s not just evident in a macro-view but in individual postings.

Today’s reading with Fr. Mike included Numbers 15, and if I’m writing about it, you can probably guess why: more brutality. Verses 32 through 36 read

Today’s reading with Fr. Mike included Numbers 15, and if I’m writing about it, you can probably guess why: more brutality. Verses 32 through 36 read