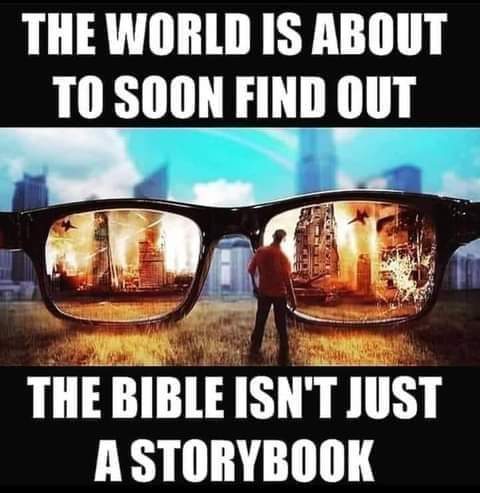

I encountered a meme that got me thinking about the relationship between Christianity and conspiracy theories. It was a meme dealing with the supposedly soon-coming apocalypse that will usher in the end of the world and the return of Jesus (if you’re a post-trib millennialist, I guess).

This sort of hyperventilating anticipation of being able to say “I told you so!” is fairly typical of the fundamentalist Christian mindset, and it’s one of the reasons I’d be nervous having a fundamentalist Evangelical in the White House: he (and it would certainly be a “he”) would be tempted to make decisions based on a sense of what might help prophecy along. At any rate, the meme suggests that skeptics will soon be put in their place:

This sort of gnostic conspiracy theory is part and parcel of the Evangelical tradition. They await anxiously the events suggested in the meme, and the suggestion that Christians have been waiting for 2000 years for something like this is wasted breath. Every Christian generation has had a portion of people who are sure that they are the last generation. Indeed, Jesus himself in the earliest gospel seems to think this:

And he said to them, ‘Truly I tell you, there are some standing here who will not taste death until they see that the kingdom of God has come with[a] power.’

Mark 9:1

I grew up in a heterodox sect that took this gnostic conspiracy theory nonsense to the next level, suggesting that its members (numbering less than 150,000 at its peak) were the only true Christians on the entire planet. That’s probably why I’m so skeptical of this nonsense.