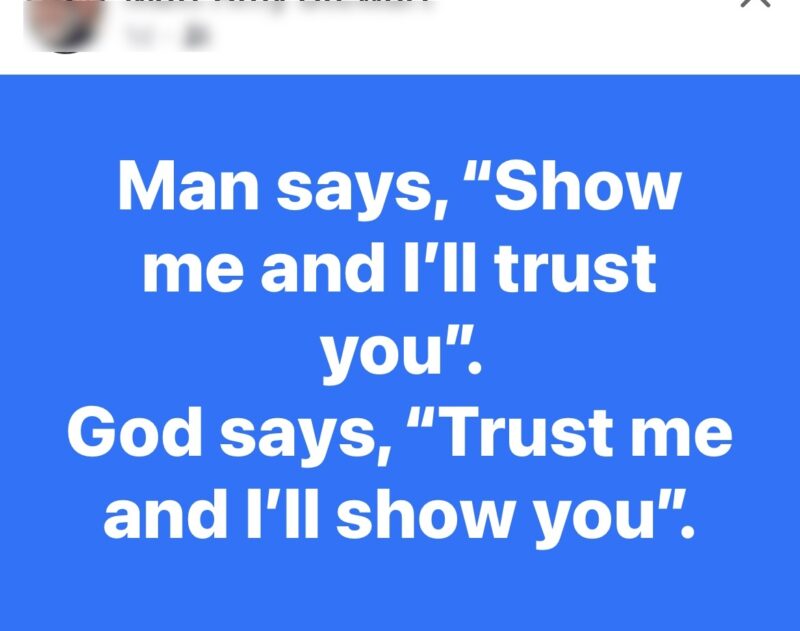

I saw a meme the other day that got me thinking about the nature of faith. A high school friend, who is a pastor and lovely human being in every sense, posted the following thought:

The problem with this is simple: this god never says anything. All we have are people saying that this god has said something. The meme should read:

Man says, “Show me, and I’ll trust you.” Some people say God says, “Trust me, and I’ll show you.”

That puts things in an entirely different situation. The dichotomy is not between a supposedly-fallible self and an supposedly-infallible deity. The division is between trusting your own senses and experiences versus trusting claims someone else makes about a deity. The first quote is asking for evidence; the second is asking for blind faith.

I’ll go with evidence every single time.