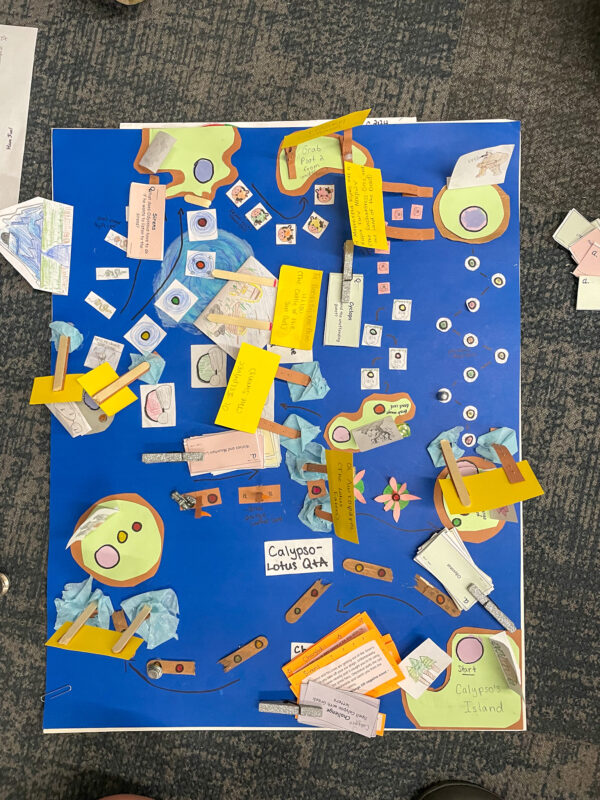

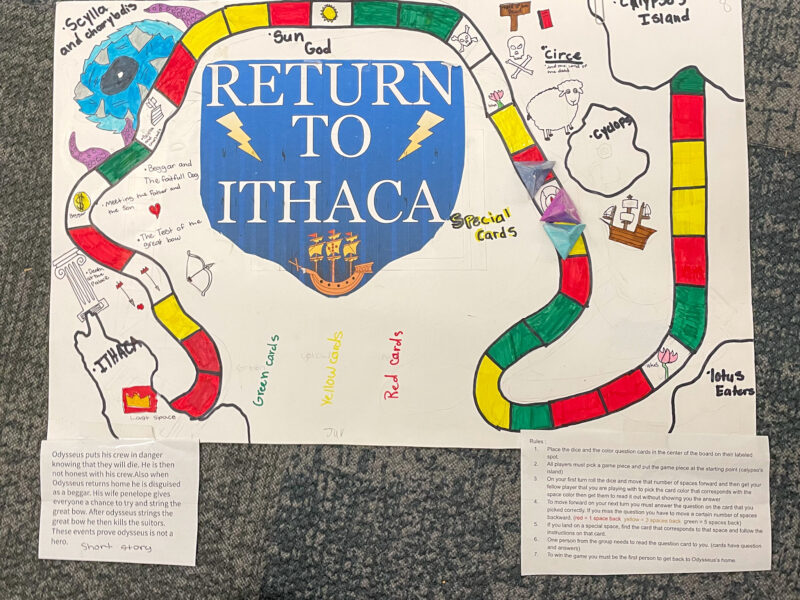

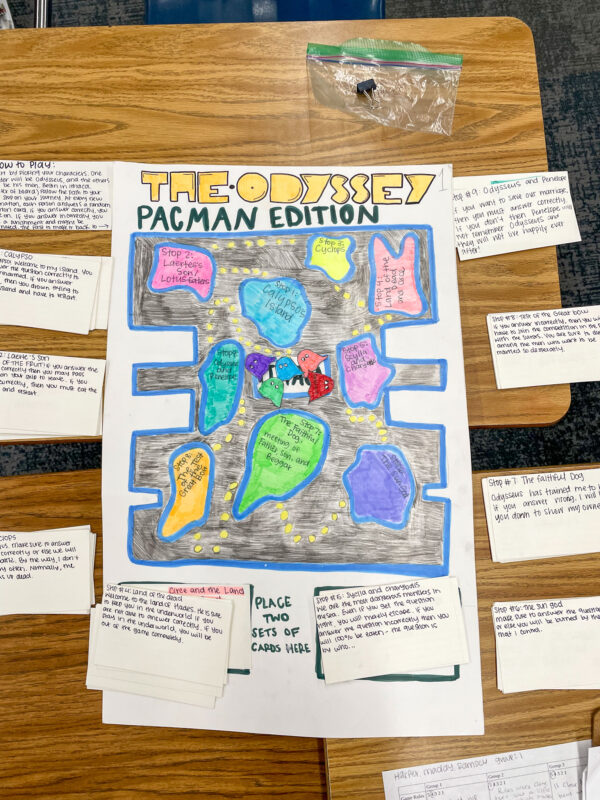

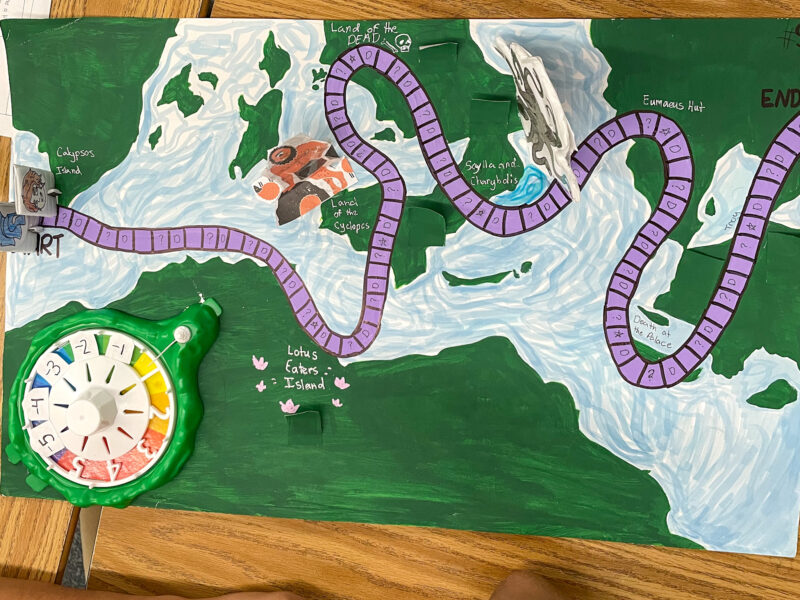

English I kids finished up their Odyssey board game project with a couple of days’ game play.

We’re looking into various middle schools for the Boy. Tonight, we went to listen to a band concert at a local middle school: the Boy is, after all, very interested in music.

His verdict: it was fun.

A forgotten post

It’s late October. The first quarter is drawing to a close, and students sit wading through district-mandated benchmark tests. Despite this, it’s one of my favorite periods of the school year. The honeymoon period is over, and we’re up to our noses in work that occasionally seems like it might sweep over us all. The kids are getting comfortable with the demands of an honors course, and we’ve all settled in for several months of work. But more than that, more personal, when I look out over the class, the students are now not just faces to which I’m trying to attach names; when I scroll down the roll at the start of each class, the names are not just sitting there waiting for me to combine with a face.

They’ve emerged as this amalgamation of worry and laughter, of procrastination and focus, of silliness and maturity — everything that makes thirteen-year-olds and fourteen-year-olds thirteen-year-olds and fourteen-year-olds. They’re still kids but in bodies that are nearly fully developed, and the awkwardness that implies radiates from every smile of accomplishment and glistens from every tear of frustration that accompanies the eighth grade. Their brains, developing in new and unexpected ways, are awash in a warm flood of newly-released hormones. They realize they’re not adults yet but in some sense are convinced they are. They’ve become people that I think I might actually have quite warm feelings toward instead of just a list of names an administrator has handed me.

I look around the classroom and see faces behind which are entire universes of experiences, worries, excitements, concerns, joys, and doubts. Each face is a mixture of all these things and more.

I see B, who’s new to public school and worried the effect her shyness and lack of experience might have on making friends but who is, nonetheless, making friends because she is a genuinely good soul and everyone sees that. I glance over at J, sitting with his head down, a child I suspect is just on the edge of the autism spectrum, who seems just enough aware of his social awkwardness to be annoyed but not defeated by it. H sits in front of the class, a teacher’s dream in so many ways: quick, bright, kind, helpful, she would probably be accused of being a teacher’s pet if it weren’t so obvious that she does these things because it’s just the person she is. In the corner desk is D, who has a mouth that seems incapable of pausing at times yet is impossible not to like despite his frustrating behavior. In the middle of the room sits quiet J, who struggled mightily at the beginning of the year and wanted to leave the class but has in the last weeks blossomed into a determined but struggling writer who has shown more improvement in the last month than some students show all year because she is so very determined to make that improvement.

In short, it’s the time of year that I realize I was wrong in my assumptions at the end of the last year, just as I am wrong every year.

“I love these silly kids!” I think at the end of the year. “There’s no way any other group can compare to them.”

And then the next year’s students come, and over the course of a few weeks they go from being names on a list to kids I’m working with, laughing with, fighting with, crying with, and I see that the impossible has happened: once again, I have the greatest group of kids I could ever imagine working with, and I’m equally convinced that they are irreplaceable, that I can never feel for another group of kids what I feel for these kids.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned in my years in the Greenville county school system it’s that nothing last forever.

Don’t like some software the district is requiring you to use? Don’t worry: the powers that be will change their mind in a few years. (I’m lookin’ at you, Mastery Connect.)

Tired of all the jargonistic names of things? Never fear: they’ll create new jargon and new acronyms based on it shortly.

Don’t like the required verbiage in the district’s lesson plan templates? Don’t fret: they’ll change that within a few years.

Feeling antipathy for the district’s teacher evaluation program? No worries: they’ll change it in a few years.

Don’t like the required template for self-reflection and the format of the accompanying meetings with administrators regarding such self-reflection? Don’t worry: they’ll change that.

Every year they change something. And every year, we hear the same thing: “This new gadget/program/template/software is a game changer.” Always looking for that silver bullet.

The only constant thing in this school district is the inevitable major change every few years.

At first, this used to bother me greatly. Not anymore. I’ve come to expect it. Every time we have a meeting, my thought is, “Okay, what are they changing now.”

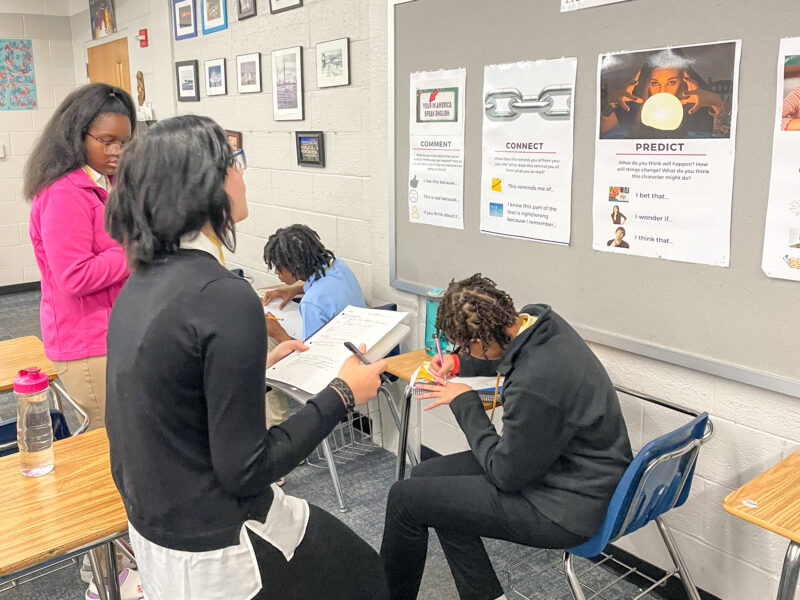

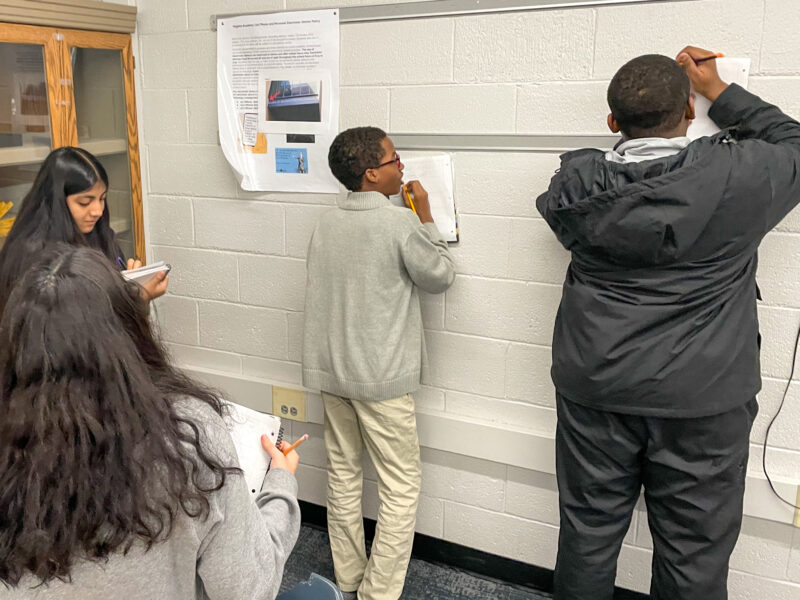

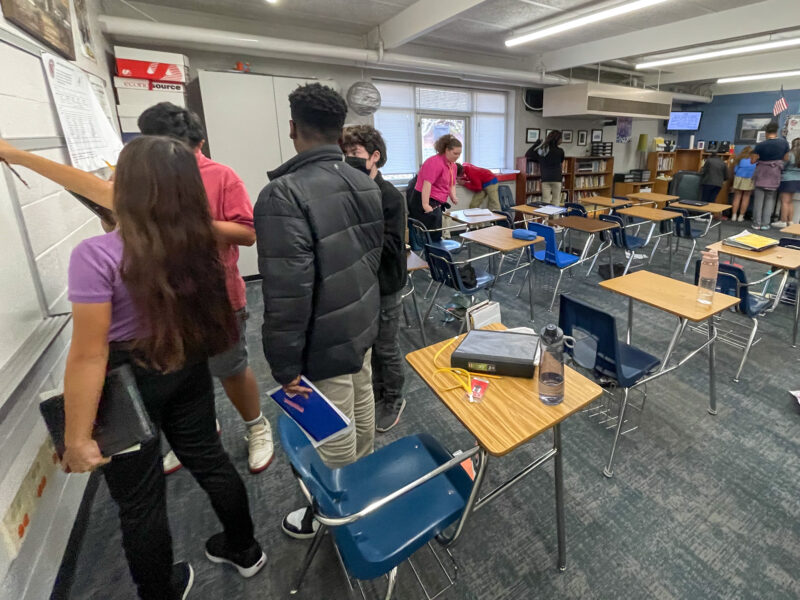

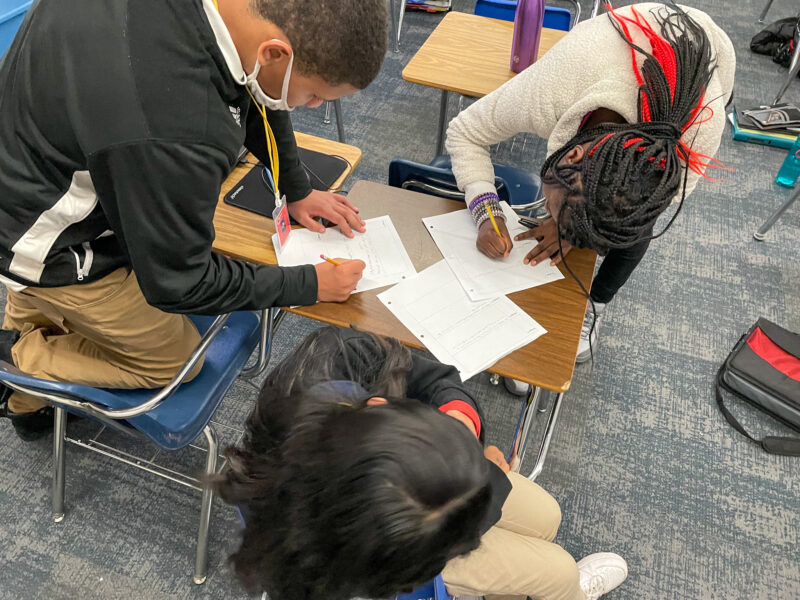

Students today began an incredibly short Halloween unit that will focus on irony, so we did a quick review of irony with a gallery walk. It’s always a fun activity: the kids move around the room, looking at various images or texts and discuss them with a particular end in mind. Today, for example, they were to determine how each image was ironic.

“Don’t just explain what’s going on in the picture,” I clarified after we’d done a quick review of what irony is. “If you don’t explain the expectation and how that expectation was defied, you haven’t explained irony.”

In the evening, the Boy and I went out to find basketball shoes for him as he begins his basketball season.

At first, I was hesitant: “They’re somewhat expensive,” I texted K, “and I don’t really know that he needs them.”

“He only has one pair of shoes,” she replied, “so he’ll need another pair soon enough.”

I looked at him: “Will you wear these to school after basketball season?”

“Of course!”

They’re tough classes at times, filled with a mix of students with mixed motivations and mixed ability levels. And all of this manifests itself in students’ behavior: several students are focused and hardworking while a few are determined to gain attention by any means necessary, with the vast majority simply there, engaged sometimes, bored and checked out others.

But there’s one activity that always gets good results: Socratic Seminars.

If I could have these on a biweekly basis, I think I could have a serious motivator for the students. So why don’t I do it? That’s a very good question, indeed. I shall be working them into plans one way or another on a much more regular basis based on how well students engaged in their first seminar of the year.

And I haven’t even done one with my honors students yet…

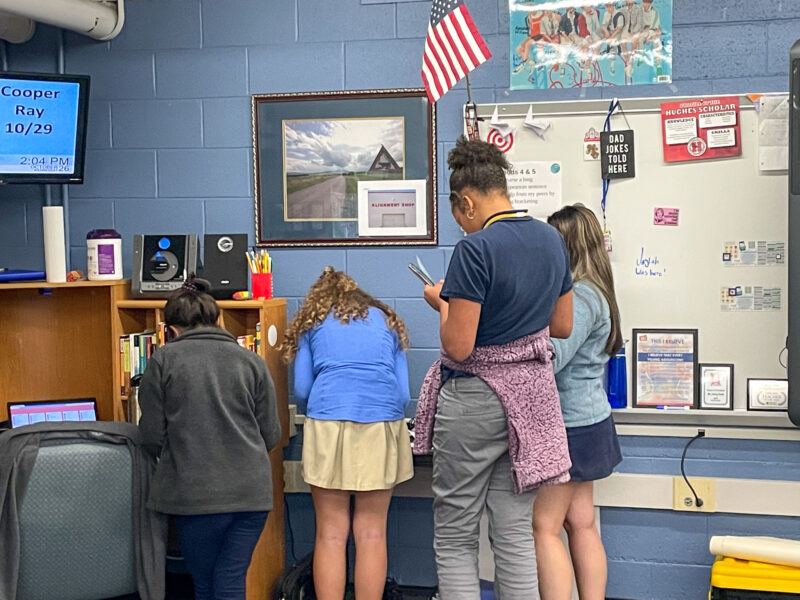

We have a new student as of today. She doesn’t speak much English at all. The language she does speak — there’s only one person in the whole school who speaks it. Her sister. Who speaks less English than she does. What did four young ladies do when she arrived in my English class? Swarm around her with welcoming smiles and helped her the entire class period.

It was hard not to feel a little hope for humanity glancing over at them as they worked through today’s assignment.

“I don’t want to be recorded.” I looked up and saw Thompson and thought at first she was joking, that she was sort of pretending to be a student. A sort of inside joke: “We both know that’s coming.” But I know her well enough to realize she doesn’t have that kind of deftness. I don’t think she even knows how to make a joke. I can’t remember what I said — I was standing by the computer, working to get everything ready for the class as they entered, and my attention was not focused on what she was doing.

“I don’t want to be recorded,” she said again, confirming what I’d suspected: she wasn’t joking.

“Okay, we can talk about this in just a moment. I’m trying to get things ready for class.” That’s what I said; what I thought was, “What in the hell is she talking about? Is she serious? How does she function in the school? Does she not realize that she’s recorded all the time? In stores. In homes possibly. Everywhere.” I kept trying to get things going and again I hear it.

“I don’t want to be recorded.”

At this point, I was thinking that we’d have an issue about this in the future, but I was slowly realizing that she wanted me to comply then. “Oh, I’m so sorry. Let me turn that off,” is what she was expecting to hear. She wasn’t letting me know that she wanted this to be taken into consideration in the future. She wanted it then.

“Well, I’m sorry,” I responded, still trying to get the materials ready for the next class, most of whom were in the room at that point.

By this time, she was getting noticeably upset. “I don’t want to be recorded,” she said again, at which point I almost said, “Jesus, lady — you’re as bad as the kids.”

In the end, she said she was going to go to the library, and I could send some kids there. By this time, the class was spiraling out of control because I was dealing with a teacher acting like a four-year-old instead of applying the same routine I’ve used daily. Once I got everything under control, the phone rang. It was Allison in the front office.

“Mrs. Thompson won’t be with you today,” she began, and I thought, “Jesus — I know this. You don’t have to tell me she’s in the library.” Instead, she continued, “She’s gone home.”

I’ve been thinking on and off all weekend about tomorrow and what that might be like. I have no idea what Thompson is going to be like; I have no clue what she’s going to say to me, to Davis, to Finley. She’s not the most reasonable person I’ve ever met, and she’s certainly not the sharpest person I’ve ever encountered, so I have this not-so-latent fear that it will be a disaster tomorrow.

Best-case scenario: I apologize and say I could have handled it better, and she says she was perhaps a little unreasonable. I volunteer to limit recording of the class in the future, and she suggests that it shouldn’t be too big of a deal, that it’s something she could get used to. I don’t see that kind of introspection in the woman, though, so I doubt that will happen.

Worst-case scenario 1: she quits, and the whole Special Ed program gets thrown into disarray. Four teachers (Haenlein, Hinner, presumably Woodard, and I) would all lose our inclusion teacher, and I have no idea the legal repercussions of that. Truth be told, the woman is more of a hindrance than help in class with her continual tendency to begin talking to students privately while I’m addressing the whole class. (Bringing that up will now be tiresome.) So not having her in class would not be a problem for me at all. But there’s the legal issue with compliance for the IEP.

Worst-case scenario 2: she becomes passively-aggressively disruptive in class. I don’t know if that is realistic: she doesn’t seem like she’s sharp enough to pull that off, truth be told.

Worst-case scenario 3: I get in trouble for what happened. That’s unlikely: I’ve already spoken to Davis about it, and her reaction reassured me, as did Haenlein’s and Rutzer’s.

What will actually happen will likely be something I’ve not foreseen, something completely unexpected. And I’ll deal with it like an adult.

Some days are so weird, so unexpected, so strange, so off-kilter that when everything finally calms down, when everything finally slows enough that you can take stock of the day, that you can take a breath and exhale slowly, that you can reflect on the oddities of the last 14 hours — those days reach that celestial moment, and you can only smile and ask, “What the hell was that?”

I try to support my students by attending one of their sporting events. Tonight, I watched the girls play a volleyball game.

So very different from the volleyball I’ve become accustomed to. Beginners are fun to watch, but they can be sadly predictable with the occasional lack of skill. It’s all part of the learning curve, no doubt.

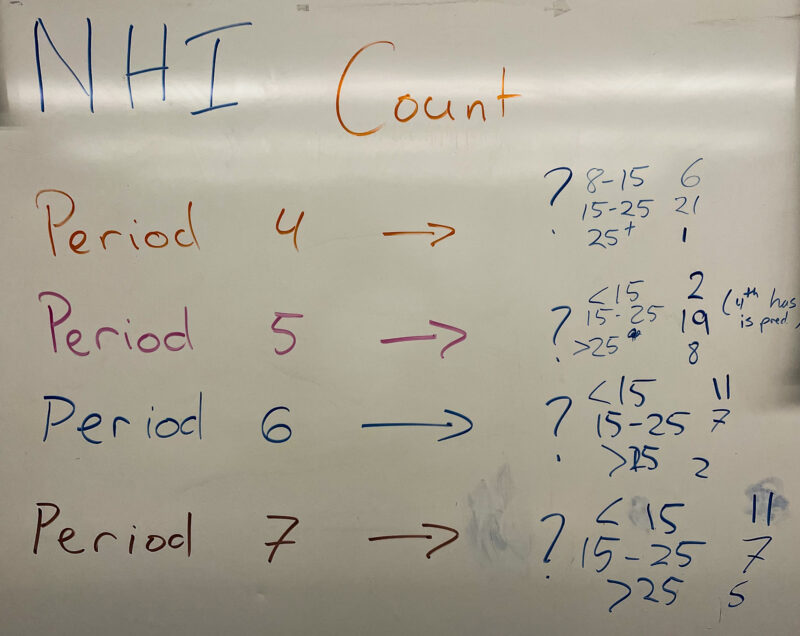

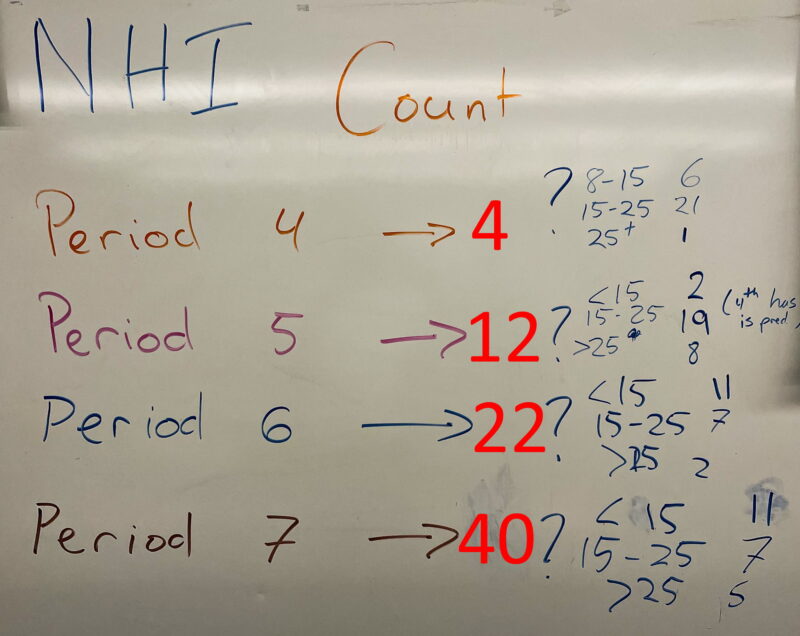

We have an epidemic of NHIs in the eighth grade. NHI is the code we enter for a graded assignment the student failed to turn in. Not Handed In.

I had a talk with my classes about the issue. On Thursday, I had students in each class guess the number of NHIs in their class for English. There were three options:

The two English I classes were certain they had between 15 and 25 per class. The two English 8 classes were certain they had fewer than 15.

The results for all classes were the exact opposite of what they expected.

The English 8 students refer to the English I (high school English) classes as “the smart kids’ class.”

“They’re not the smart kids class,” I always reply, but Friday, when I revealed the results, I added, “They’re simply the do-the-work kids class.”

Sometimes, there’s a certain relief when we realize we’ve finished a unit of study.

The first pack meeting today — the meeting two weeks ago was technically just a get-together, I suppose. The boys, as always, played Gaga ball afterward.

“This game hadn’t even been invented when we were kids,” one dad laughed as we watched them play.

Class today was excellent again. The main difference: like Tuesday, I tried a long, breathing-based mindfulness activity early in the lesson. Amazing how calm it made a bunch of otherwise-antsy kids.